‘We had to disrupt British society; that was absolutely clear.’

2 March 2016 marked the 35th anniversary of one of the most significant political demonstrations in 20th century British history, and one which deserves to be better remembered. Around 20,000 people marched across London to protest against the racist murder of 13 young black people in the New Cross fire six weeks earlier. The Black People’s Day of Action brought large parts of the capital to a standstill and marked a turning point in the struggle of black people against the racist institutions of the British state, laying the ground for the uprisings in Brixton, Liverpool 8, Moss Side and other inner city areas, which were to follow in the months and years ahead. FRFI took part in the demonstration and we wrote at the time that:

‘…the March was a fine example to the working class. It put to shame the so-called revolutionaries of the petit-bourgeois left who allow the police to play havoc with their demonstrations, arrest and beat people willy-nilly and do nothing about it. This demonstration showed that the vanguard forces of the British revolution are the black youth who will fearlessly take on and do battle with the forces of the state. In doing so they are showing the rest of the working class the only way forward in the struggle against oppression.’ (FRFI 9 – March/April 1981)

New Cross fire

On 18 January 1981, 13 young black people died in a fire started deliberately at a birthday party on 439 New Cross Road, South London. It marked the bleakest moment in a decade of extreme violence directed at the black community both by the state and by fascist thugs. The political class and the media stoked a climate of racism in which horrific levels of brutality, including murder, became routine. The incidence of racist attacks was closely related to government and media-inspired resentment against immigration; of the 64 racist murders between 1970 and 1986, 50 occurred in the five years – 1976 and 1978-81 – when immigration scares ‘reached fever pitch.’[i]

The New Cross fire occurred in the context of racist arson attacks across South London. Both the Moonshot youth club in New Cross and the Albany centre in Deptford had been burnt out by fascists in the preceding years; in 1971, three petrol bombs had been thrown into an African-Caribbean party in Ladywell. The immediate response of the police was to arrest eight members of the Black Unity and Freedom Party on their way home from visiting victims in Lewisham hospital.

The response of the police and the press to the New Cross tragedy was the same as in every instance of racist violence – to deny that a racist crime had taken place at all. In an insightful article from 1990 entitled ‘ATTACK NOT RACIST, say police’, the Scottish novelist and working class fighter James Kelman wrote that: ‘In case after case, in crimes of racial violence…the first requirement of the State is to prove the crime did not take place; that it was another crime altogether, a crime which may well have been violent, a murder even, but not a crime that was racially motivated. Why is there such a requirement? This appalling breakdown of justice has forced members of the black communities to act on their own behalf.’ [ii]

In the wake of New Cross, the Metropolitan Police fed stories to the media about gate-crashers and cannabis, detained black youth for questioning and twisted evidence at every turn to ‘prove’ that the fire was not started by racists. This cover-up was aided and abetted by parliament and MPs. Despite the fact that the New Cross massacre was the worst atrocity suffered by black people in Britain, it took the Day of Action to force MPs to raise it in parliament. Local Labour MP, John Silkin, said not one word in the House of Commons and for three weeks did not send even a message of condolence to the families. As one woman stated at a press conference, if the fire had taken place in a dog’s home and killed 12 dogs, there would have been more response (FRFI 9). A coroner’s inquest in 1981 returned an open verdict, refusing to rule that the fire was the result of a racist attack. A second inquest in 2004 returned the same verdict. Thirty-five years on, no charges have ever been brought.

Independent intervention

In the face of the press lies and distortions, police inactivity and parliamentary indifference, the black community faced a straightforward choice: ‘either reject the law and settle for justice, or accept the law and leave justice in the hands of the police and the legal system’. On the Sunday following the fire a mass meeting was held at The Moonshot Club, attended by over 1,000 people. From there, a spontaneous demonstration was held outside the site of the fire for several hours. ‘They were trying to move us but they did not dare.’ A New Cross Massacre Action Committee (NCMAC) and Black People’s Assembly were formed and mass meetings held across London and up and down the country. An independent Fact Finding Commission was established to counter the disinformation of the police’s media strategy and meet the 1981 inquest with a clear line of defence.[iii] ‘For us the courts were also an area of political struggle.’ (John La Rose)

The independent proletarian spirit, creativity and revolutionary standpoint of the NCMAC was in total contrast to the staid, collaborationist traditions of the official labour movement. The decision to organise a Black People’s Day of Action arose from the mass meetings of the Black People’s Assembly. John La Rose, the chair of the NCMAC, recalled in an interview:

‘People would be saying, “Man we have got to do something about this thing. The police cannot get away with this thing!” That kind of talk went on. And they said, “Yes we’ll go on a march.” “Where are the guns?” That kind of talk…And I said, “Have you heard of a man called Brigadier Frank Kitson, Low Intensity Operations? If you haven’t read his book then you should read it. Because if you are talking about going to Parliament with guns then you have to take on Kitson.” He had been the Commander in Northern Ireland, he was GOC in Britain. I said, “Let’s talk seriously, you are starting at the end, let’s start at the beginning.”

‘We had that sort of interchange all the time at the meetings, very open, free meetings. So they said, “OK we’ll go on a march.” We said, “Well, what day are we going to march?” Because the normal marches took place on a Sunday, when nobody’s working, everyone’s home, the people said that they wanted it to be on a day when the British are bound to take notice. So what day? We had to disrupt British society; that was absolutely clear. That is what we were saying in that movement. We wanted to snarl up traffic all over London.

‘So we decided it must be a Monday; that came from within the audience. We wanted to make this place realise that we’re serious and we’re going to disrupt the whole of British society. We aren’t going to work that day…

‘What demonstrations in the past usually did was to march on Hyde Park into Whitehall. We said we were going to go where the people are going to know that this is happening, we’re going to march in all those areas – like Peckham – before we come to Blackfriars Bridge. That way you are going to hit that area of London with all those people who are really concerned about what’s happening in the whole New Cross area, and then march through the financial centre, the City, and shake up the place, terrify them.[iv]

In his 1979 song Independent Intavenshen, Linton Kwesi Johnson, who was involved with NCMAC, had written

‘The SWP

Can’t set we free…

‘The CRE can’t set we free

The TUC can’t do it for we…’

The Black People’s Day of Action was not only a revolutionary challenge to the racist institutions of the British state, but also to the spinelessness of a British left which allowed the police to determine the parameters of struggle.

The Black People’s Day of Action

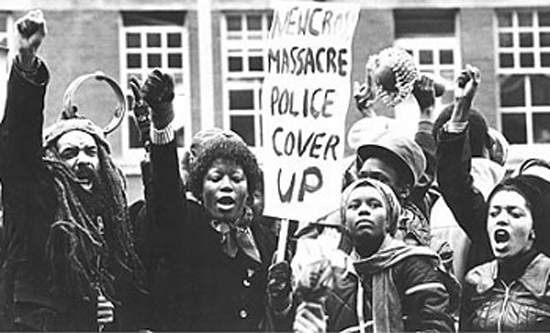

On Monday 2 March 1981, around 20,000 black workers, families and supporters marched eight miles across London. Placards and slogans made their feelings clear: ‘New Cross Massacre Cover Up’; ‘Forward to Freedom’, ‘Babylon will fall’; ‘No stopping us now we are on the move’; ‘No Rights, No Obligations’.

From New Cross to Hyde Park, traffic in central London was brought to a standstill. Youth fought to break through police lines at Blackfriars Bridge and the march surged into the heart of the City. As FRFI reported: ‘city gents cowered in their offices terrified at the sight of the oppressed demanding justice’. The symbols of wealth – a bank and a jeweller’s shop – ‘fell victim to a hail of bricks and stones: journalists who quite rightly are seen as siding with the racist British state got rough justice…when a youth was arrested the march came to an immediate halt shouting “Let him go!” which police were forced to do as the marchers refused to move without their captured comrade.’

Despite the provocation of riot police and mounted charges, the march completed its agreed route with discipline. The New Cross declaration issued on the day stated:

‘The New Cross Black People’s Day of Action is another stage in the response of the black people, of our allies in the country to this savagery and this barbarism. We warn the country and the world there will be no social peace while blacks are attacked, killed, injured and maimed with impunity on the streets or in our homes.’

The March demonstrated above all that black people ‘would not be the victims of racism, but revolutionary fighters against their oppressors.’ (FRFI 9)

Racist response

The racist response of the millionaire press to the 2 March was predictable. The Sun raved of ‘a frenzied mob’. Headlines screamed ‘The Day the Blacks Ran Riot in London’.

Also predictable, but even more shameful, was the response of the petit-bourgeois left. The Communist Party (CP) wrote: ‘No one is going to excuse the outbreaks of violence which undoubtedly took place.’ In contrast, FRFI wrote ‘How wrong the CP is. All true revolutionaries and communists will see the resistance of the youth as a splendid example of revolutionary working class means of fighting oppression. Far from needing to “excuse” it we rejoice that one section of the working class is on the road to revolution.’

Legacy

Unlike the Battle of Cable Street or even the anti-fascist demonstration in Southall, April 1979, the Black People’s Day of Action has not claimed a place in the popular consciousness of struggle. Yet, as John La Rose commented: ‘it was something that had not happened since the Chartists back in the 1830s. People had not marched across London into the City.’ The demonstration – together with the Action Committee’s establishment of an independent commission into New Cross and the determination of the families to fight a political battle through the courts – was crucial in forcing the coroner to return an open verdict in the 1981 inquest; in other words, not allowing the police to ‘prove’ that the massacre had not been the result of a racist attack. This struggle was key to establishing racist motives as a cause in subsequent attacks. In the month after the demonstration, the Brixton uprising exploded and marked the intensification of the struggle of the black working class against the British state.

The Black People’s Day of Action is a great reminder of the unlimited creative reserves of the oppressed in the face of the brutal realities of British society. It is an example we must heed today.

The victims of the New Cross fire were Humphrey Brown, 18, Peter Campbell, 18, Steve Collins, 17, Patrick Cummings, 16, Gerry Francis, 17, Andrew Gooding, 14, Lloyd Richard Hall, 20, Patricia Denise Johnston, 15, Rosalind Henry, 16, Glenton Powell, 15, Paul Ruddock, 22, Yvonne Ruddock, 16, and Owen Thompson, 16.

Joey Simons

- [i] Keith Thompson, Under Siege: Racial Violence in Britain Today (Penguin, 1988)

- [ii] James Kelman, ‘ATTACK NOT RACIST, say police’ in And the judges said… Essays (Polygon, 2008)

- [iii] For full account and documentation, see New Cross Campaign Material in the George Padmore Institute Archive Catalogue (Ref: GB 2904 NCM)

- [iv] James Kelman, ‘An interview with John La Rose’