Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism, No. 102, August/September 1991

The level of public expenditure and taxation has been the cause of much noise and posturing between Labour and Tory politicians over the last few months. The more their future policies have tended to converge, the more vociferous are the accusations thrown. Labour says the Tories will deliberately slash public spending to open the door to further privatisation and tax cuts for their supporters. The Tories say that Labour is planning a massive rise in taxation to finance its huge public spending plans. In reality both parties have little room for manoeuvre as Britain’s relative economic decline gathers pace and the recession deepens.

In a recent Editorial ‘British capital – little room for manoeuvre’ (FRFI 100 April/May 1991) we pointed out how in the mid-1970s the social democratic consensus between capital and the working class, which had been a dominant feature throughout the post-war boom, broke down. The rising consumption institutionalised in the Keynesian welfare state became a barrier to capital accumulation and was no longer feasible given Britain’s relative economic decline.

Memories are, however, short especially where class interests are at stake. The petty bourgeois left still dream of reviving Keynesianism. This is not surprising.

The relative prosperity in the imperialist nations during the post-war boom gave rise to new relatively privileged sections of the working class – a new petty bourgeoisie. This layer of predominantly educated, salaried white collar workers grew with the expansion of the state and services sector and, in the more recent period, with the information technology revolution. The privileges and status of this layer rests on the continuing prosperity of imperialism.

The small forces of the British left draw their membership primarily from these new relatively privileged layers of the class and adapt to all its political prejudices and narrow eurocentric world view. This is the foundation of the left’s apparently unbreakable bond with social democracy and its ambivalent stand in relation to British imperialism. At every stage as the material basis for sustaining a growing public sector was undermined the left demanded the process be reversed, putting forward programmes and strategies which sustained their link with the Labour Party and within a framework compatible with social democracy.

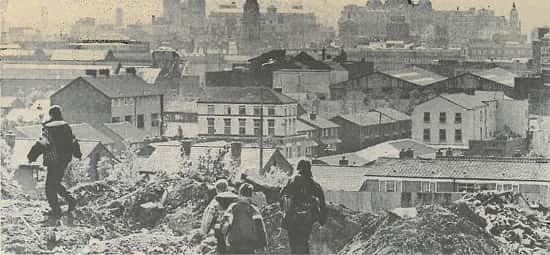

In the late 1970s we had the ‘left alternative strategy’ – a state-induced national programme of investment which flew in the face of the crisis of Keynesian state intervention in the economy. It was totally ignored. By the early 1980s we had those glorious havens of municipal socialism which, by the end of the decade, had shown they could not withstand the dual onslaught of Thatcher’s attack on local government and Labour’s headlong retreat into ‘new realism’. The last ditch stand of municipal socialism is now being made in Liverpool and has even forced, albeit very reluctantly, Militant out into the open, finally exposing the widespread illusion that it is possible to subvert the Labour Party from within.

These political developments show that national Keynesianism has come to an end. British imperialism cannot sustain a traditional social democratic state. It was precisely Britain’s economic decline in the face of the challenge from a resurgent German and Japanese capitalism which threatened Britain’s standing as an imperialist power and underlay the breakdown of the Keynesian welfare state. Thatcher’s economic programme, in particular, the sustained attack on public sector spending, was the inevitable ruling class response to this development, a futile attempt to halt the decline while sustaining Britain as a major imperialist power.

The social democratic left is, however, unable to face up to this reality. A recent article in Marxism Today, ‘Europe’s Tax Exiles’ by Bob Rowthorn compares Britain unfavourably to Europe.

In 1969 Britain had the third highest ratio of government spending to GDP in the Western world, surpassed only by Holland and Sweden. Today the government accounts for a lower share of total spending in the UK than in any other country of the European Community. And of all Western countries Britain is the only one where government expenditure in relation to GDP has actually fallen since 1969.

A similar picture arises with taxation and other kinds of government revenue. The share of government revenue in GDP is much the same in Britain as 20 years ago, whereas for most other countries there has been a substantial increase. The overall tax burden in Britain is well below that of most comparable European countries. Rowthorn tells us that if tax rates were set at the German level in this country the government would have an extra £20bn to spend every year. With French rates it would be £40bn and with Dutch or Scandinavian rates £60-80bn extra. The mouth waters at such a bounty. More than enough to satisfy the requirements of even the most demanding petty bourgeoisie.

There is, however, a problem. Rowthorn is forced to admit that no political party in Britain is going to take steps to raise taxes to European levels in order to create a European-style welfare state. The Tories, we are told, will not do this out of ‘ideological predilections’; Labour, having accepted the broad outlines of Thatcher’s tax policies, cannot do it. To advocate a change of policies at this stage would be political suicide.

In the mid-1970s Rowthorn was an advocate of the ‘left alternative strategy’. At the time he argued that a left wing government could only put such a strategy into practice by breaking ‘the power of the capitalist class in Britain’. It could not be done by passing appropriate laws in parliament ‘but requires the mobilisation of ever wider strata of working people in ever more political struggles’ (Britain’s Economic Crisis, Spokesman Pamphlet No44 p25). Time has, however, moved on. The class struggle is no longer in fashion with Rowthorn and his kind. The Labour Party has moved rapidly to the right to get itself elected and Bob Rowthorn has become a Cambridge professor. So, failing class struggle, how are we to create a European-style welfare state if Britain’s relative economic decline has destroyed the material basis for it?

A European-style welfare state in Britain today would require a determined class struggle against capitalism. Rowthorn tries to sidestep this. Some 17 years on, all that remains of his social democracy is a kind of alchemy – adjustments made in his head are deemed to be possible in reality.

Hence he tells us that from the mid-1980s onwards in Britain, incomes rose by 25 per cent and there was no need to reduce the overall tax burden. The £20bn saved on cutting public expenditure, and which provided most of the finance for cutting taxes at the expense of the less well paid workers, benefit claimants and the poor, was not necessary. Tax burdens are not the disincentive suggested by the Tories, and swallowed by Labour, as the example of Japan with a top tax rate of 65 percent shows. Neither is Britain too poor to afford a European-style welfare state as its GDP per head is higher than many countries in Europe.

Economic and political reality are simply ignored. Not only were the tax cuts politically necessary to ensure the re-election of successive Thatcher governments, but they were also designed to transfer wealth from the ‘unproductive’ state sector to private capital in order to boost profitability and restore Britain’s competitive position. That this failed reveals the depth of the British crisis, something Rowthorn understood many years ago. ‘The current crisis is not an isolated event, but simply a severe manifestation of the deep-rooted structural problems which have plagued the British economy and British society for the last century.’ (ibid p6)

Britain’s relative economic decline has accelerated over the last 12 years despite the benefit of more than £100bn from North Sea Oil and the growing income from Britain’s investments abroad. These benefits have now been considerably reduced. Public spending is increasing and public sector borrowing of between £12-13bn in 1991/2 will be necessary not to create a European-style welfare state but because the recession has forced both a loss of income and extra spending on an unwilling government. Britain could indeed face a sterling crisis as interest rates fall and the £84bn foreign holdings of sterling are moved to less risky climes.

Rowthorn knows all this but like a drowning man clutching at straws chooses to see in it a possible solution to his problem. Faced with increasing demands on social expenditure as the recession deepens and unemployment grows, a future Labour or even Tory government, says Rowthorn, faced with the stark choice of cutting public spending or increasing taxes might well choose to raise taxes. This would be seen as an emergency measure, but once they were raised then it is unlikely they would be ever brought down again under a Labour government. Hence the taboo of raising taxes could be broken and eventually it could become politically acceptable again to finance an improved welfare state through increased taxes.

Of such dreams are petty bourgeois illusions, hopes and aspirations made. Rowthorn has forgotten what he took for granted in 1974, that ‘Labour’s willingness to act as an administrator of British capitalism’ (he should have said imperialism) makes it renege on its commitments, and Labour governments have eventually ‘imposed a wage freeze, cut social services and created unemployment’ when in power (ibid, pp10-11). Kinnock’s Labour Party hasn’t got as far as even making the commitments.

Yesterday’s self-proclaimed communist and his Labour left allies’ programme essentially consists of two proposals: raise taxes and raise the moral climate for this to be done. They will not accept that it was the need to sustain Britain as a major imperialist power which forced British governments, Labour and Tory, to take the economic and political paths they did. For it would be tantamount to admitting that their own privileges, together with those of the petty bourgeois class they represent, can only be guaranteed by the existence of British imperialism.