FIGHT RACISM! FIGHT IMPERIALISM! 138 AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 1997

15 August 1997 marks the 50th anniversary of the formal independence of the Indian sub-continent. ROBERT CLOUGH outlines the course of the struggle to end British colonial rule, how British imperialism was able to ensure that it ended with a neo-colonial solution, where political independence masked a continuing domination by imperialist rule, and how the Labour Party would be critical in achieving this aim.

India was truly ‘the jewel in the crown’ of British imperialism. From 1757, when Clive’s victory over the Mogul of India started the plunder of Bengal, India was a source of untold wealth, exceeding even that generated by the slave trade. The results were no less destructive: the imposition of capitalist relations on the Indian rural economy led to regular famines during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, whilst Bengal itself was reduced from conditions of development equivalent to those in Britain at the end of the eighteenth century to the abject poverty that characterises the Bangladesh of today. If the slave trade had created a mercantile power out of British capitalism, it was the plunder of Bengal that provided the money capital to advance the Industrial Revolution.

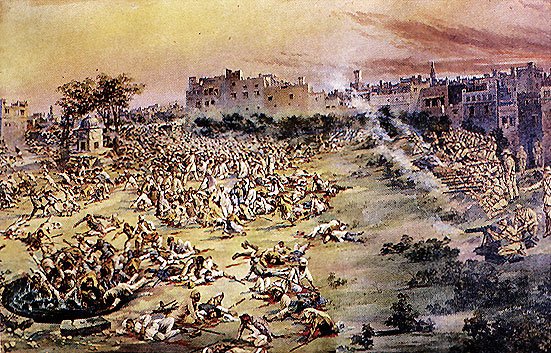

CONQUEST

The British conquest of India was possible because of its ability to exploit divisions between local feudal interests and then maintain its rule by extending and deepening them. Although there were progressive aspects to British rule — the introduction of modern forms of communication such as the railways and telegraph system, the destruction of feudal modes of existence, the establishment of modern technical education for a small section of the indigenous population — these were accompanied by the creation of a massive surplus population living on the edge of starvation through the destruction of the local textile industry (to allow India to serve as a mass market for the one being established in Britain), and by the introduction of private ownership of the land. The resulting ferment coalesced in the Mutiny of 1857, suppressed with savage brutality. This was to mark a turning point. Until that time, the policy of British imperialism had been to create a unified colony out of thousands of feudal statelets. It had encouraged substantial Indian representation in the lower rungs of the Indian Civil Service and the medical, legal and teaching professions were almost completely Indian. The Mutiny changed all this: the involvement of the dispossessed had terrified the British ruling class. From then on British imperialism allied itself with the princely states against the masses, so that the political map of India would remain a mosaic of divided fiefdoms — 565 of them, with a fifth of India’s total population of some 300 to 400 million.

THE CONGRESS MOVEMENT

Significant opposition to British rule did not emerge again until the early 1900s. In the meantime, a retired official of the Indian Civil Service, Allan Hume, had set up the Indian National Congress, and served as general secretary from its foundation in 1885 until 1908. Hume regarded Congress as ‘a safety valve for the escape of growing forces generated by our (ie British) own action … and no more efficacious safety valve than our own Congress movement could possibly be devised’, and in its early years, it acted as a debating society for the English-educated bourgeoisie. Yet it could not remain like this. Within its ranks, divisions between the wealthy landlord interests and the petty bourgeoisie — teachers, lawyers and students — began to appear, with the latter starting to agitate for independence. The first test came in 1905, with the proposal by the Viceroy of India to partition Bengal and so drive a wedge between the Hindu and Moslem populations. A mass boycott movement developed, led by the petty bourgeois wing of Congress. The colonial administration attacked it ruthlessly, jailing hundreds, breaking up meetings, and passing new repressive legislation. When one of the leaders, Tilak, was jailed for six years in 1908, textile workers in Bombay went on strike, an event hailed by Lenin. Armed organisation emerged in the struggle, adding to the threat posed to British rule, which responded by encouraging inter-communal strife. In 1911, after some minor political concessions, the proposal was quietly withdrawn. Yet the seeds of future division had been sown. Inter-communal strife had a material basis in Bengal: a section of the Moslem bourgeoisie had stood to gain from the partition of Bengal, and had opposed the boycott campaign. The result was the formation of the Moslem League, with a membership restricted to ‘400 men of property and influence’ — a sound indication as to its class nature.

‘THINK IMPERIALLY’

The next major challenge to Congress was the outbreak of the First Imperialist War in 1914, which India also entered by virtue of a declaration of the Viceroy. At each of its four annual sessions during the War, Congress proclaimed its support for British imperialism. Gandhi, newly arrived from South Africa, urged his colleagues to ‘think imperially’, but when he offered to raise a corps of stretcher-bearers for the campaign in the Middle East, the Viceroy excused him on the grounds of his ill-health, adding that ‘his presence in India itself at that critical time would be of more service than any that he might be able to render abroad’ — prophetic words indeed. By the end of the war, India was in turmoil. Britain had plundered it of manpower, finance and food resources. The first three years of the war had cost India £270 million: part of this was used to fund the one million strong army it provided to British imperialism, and which was crucial in preventing the German Army from occupying the Channel ports in its 1914-15 campaign. But it also included a forced loan of £100 million, a sum equivalent to at least £5 billion in today’s terms. And, at a time when two-thirds of the population was starving, Indian exports of wheat and cereals amounted to 2.5 million tons in 1917, and even more in 1918. The mutinous state of the Indian Army, and the impact of the Russian revolution, meant that some political concessions to the nascent Indian bourgeoisie were needed to stabilise imperialist rule. The Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, touring India in 1918, described the ‘seething, boiling, political flood raging across the country’. He proclaimed the Government’s aim as ‘the gradual development of self-governing institutions with a view to the progressive realisation of Responsible Government in India as an integral part of the British Empire.’ Together with the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, he prepared a report on the necessary constitutional changes to buy off at least one section of the Indian bourgeoisie.

‘REFORM’

The Montagu-Chelmsford reforms were based on a plan devised by one Lionel Curtis. Responsibility for three departments, education, health and local government, would be transferred to elected ministers, but only at a provincial level: national structures would remain unchanged. Even then, the vital department of finance would remain under the control of the Indian Civil Service. There would be a franchise: 3 million out of 350 million people would be allowed the vote. The progress of these reforms would then be reviewed after a period of ten years. At the request of the Labour Party, Curtis produced a pamphlet explaining his proposals for use by Labour candidates in the 1918 General Election. ‘At present’, he wrote, ‘the number of people who could understand the vote is small. To grant full responsible government outright … would place government in the hands of a very few’ — an ironic statement given how few ruled it through the Indian Civil Service at the time. However, such ‘reforms’ were irrelevant to the mass of the Indian people. Famine stalked the land: estimates as to the number who died from a combination of flu and starvation in 1918-19 range from 12 to 30 million. The countryside was a tinder-box: and starting in the heartland of the cotton industry, Bombay, a massive strike wave spread throughout the major industrial centres. The only response was repression: a Bill enacting new measures to combat ‘sedition’ and ‘terrorism’ proposed by the Rowlatt Committee took effect in March 1919. On 13 April, a meeting against the Rowlatt Act took place in Amritsar in the Punjab. Under the command of General Dwyer, a column of troops opened fire on the peaceful crowd. 379 people were murdered, 1,200 injured.

BOYCOTTS AND STRIKES

The result was an explosion. The first six months of 1920 saw 200 strikes involving 1.5 million workers. In September 1920, Congress authorised a progressively extending boycott movement. Under Gandhi’s reluctant leadership, the campaign spread throughout early 1921: spontaneous non-payment of taxes started in some areas; more ominously for the Indian landlord class, peasants started to go on rent strike. A huge general strike greeted the arrival of the Prince of Wales in November of that year. But Gandhi, now in control of Congress, ruled out an amendment to the aims of Congress to call for complete independence, and then refused to sanction a call for the non-payment of taxes. For three months, he remained silent, and then, on 1 February 1922, he sent a letter to the Viceroy, stating that unless all prisoners were released, and the Rowlatt Act repealed, he would authorise a campaign of mass civil disobedience but one confined to the tiny District of Bardoli, home to a mere 87,000 people. Hardly had the letter been sent when news came that peasants had stormed the police station in the village of Chauri Chaura and burned 22 policemen to death. Immediately, he called off the campaign complaining in the so-called Bardoli declaration that ‘the country is not non-violent enough’, advising ‘the cultivators to pay land revenue and other taxes due to the government, and to suspend every other activity of an offensive nature’, and ordering the peasants that withholding of rent payment to the landlords was ‘injurious to the best interests of the country’. For the impoverished peasants, there was little difference between paying taxes to the British authorities and rents to the native landlords. Both were part of a system that kept them in bondage. The passage from opposition to the British to opposition to the landlords was but a small step. And that is what Gandhi and Congress feared. The Bardoli Declaration was far more about the rights of property than about Gandhi’s supposed hatred of violence. The results were immediate. Gandhi was arrested, and was retired for six years to the palatial accommodation that was reserved for him whenever he went to gaol. The Moslem League split from Congress for what it regarded as its extremism, whilst another section formed the Swaraj League to contest elections to the local assemblies. Four communists were arrested for conspiracy, tried, and sentenced to several years’ imprisonment in the so-called Cawnpore conspiracy trial. The movement all but collapsed.

LABOUR BETRAYAL

Political conditions did not change with the advent of the first Labour Government in 1924. Ramsay MacDonald as both Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary stated in case there was any doubt that ‘I can see no hope in India if it becomes the arena of a struggle between constitutionalism and revolution. No party in Great Britain will be cowed by threats of force or by policies designed to bring Government to a standstill; and if any section in India are under the delusion that is not so, events will sadly disappoint them.’ And as if to underline its position, the government sanctioned the passage of yet more repressive legislation, the Bengal Ordinance, which allowed for detention without charge let alone trial.

In late 1927, the Tory Secretary of State for India, Lord Birkenhead, decided to bring forward the statutory review of the progress of the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms in order to guarantee Tory control of the Commission that would carry it out. With the complete eclipse of the Liberals at the 1924 election, Labour had become the Loyal Opposition; this meant they would be entitled to seats on the Commission. In negotiations with MacDonald on its composition, Birkenhead’s aim was to exclude any Indian representation, whilst MacDonald’s was to ensure the presence of at least two Labour members. Both achieved what they wanted, and MacDonald overruled Labour Party executive objections to the absence of any Indians. The two Labour nominees were Clement Attlee and Steven Walsh, the latter a notorious imperialist.

The enabling act setting up the Commission under the Chairmanship of Sir John Simon was rushed through Parliament by Christmas 1927. All sections of the Indian nationalist movement were outraged. The Indian TUC passed a motion demanding that Labour ‘withdraw its members from the Simon Commission’, and resolved that it itself would boycott it. Its President, Chaman Lal, protesting what he described as MacDonald’s ‘imperialist proclivities’ went on to say: ‘All classes are aghast at the betrayal by the Labour Party. The Simon Commission will register the middle class imperialist verdict.’ Pandhit Nehru, on behalf of Congress told the Labour NEC: ‘I am authorised to state that the action of the Labour Party, in not withdrawing its members from the Commission, and trying to effect some kind of compromise, is not supported by any responsible party in India.’

The Simon Commission together with Attlee arrived in India in February 1928, to be greeted by a general strike; three demonstrators were killed in a demonstration in Madras. As it proceeded round the country, it was greeted with mass demonstrations, strikes and riots. The Indian working class played a leading role: a colossal strike movement in 1928, with over 30 million days lost, was accompanied by a 70 per cent growth in union membership, with a massive growth of the revolutionary Bombay Girni Kardar or Red Flag Union. Meanwhile the 1928 Labour Conference debated a motion opposing the Commission. Fortified by a TUC report attacking the middle class leadership of the Indian trade union movement, the conference trounced opposition by 3 million votes to 150,000. No wonder Shapurji Saklatvala, the British Communist MP, reported for the Daily Worker: ‘It has been well-known for some time that the Commission would have a hostile reception from the Indian workers, who view it as the latest weapon of British imperialism… When the Bombay workers burned the effigy of MacDonald in the streets along with that of Lord Birkenhead and others, they showed that they viewed the Labour Party as nothing more or less than the willing hirelings of British imperialism.’

BRITISH TERROR

British imperialism was given breathing space by a split in the Indian National Congress at the end of 1928: whilst the left wanted an immediate campaign for independence, Gandhi and the bourgeois wing made any campaign conditional on a British refusal to accept self-government by 31 December 1929. Imperialism had a year in which to prepare. In March 1929, all the most prominent leaders of the Indian working class, including the entire leadership of the Red Flag Union, were arrested and taken to Meerut, detained on a charge of ‘attempting to deprive the King-Emperor of the sovereignty of India’. At a crucial stage in the liberation struggle, the working class movement had been decapitated.

The election of the Labour government in May 1929 brought no change to British policy. Gandhi made no response when his deadline was passed, although there were vast demonstrations on Independence Day, 30 January 1930. In the meantime, the government took the precaution of detaining the leading left-wing nationalist Subhas Bose. Finally, Gandhi announced a march on Dandi by a select band of followers to make salt in defiance of the government monopoly, to be followed by a campaign of non-co-operation. On 6 April, Gandhi made his salt and the movement exploded once more, as peasants interpreted non-co-operation to mean non-payment of rent as well as taxes. The town of Peshawar fell into the hands of the people following hundreds of deaths and casualties at the hands of loyal troops. But one incident stood out: ‘Two platoons of the Second Battalion of the 18th Royal Garwhali Rifles, Hindu troops in the midst of a Moslem crowd, refused the order to fire, broke ranks, fraternised with the crowd, and a number handed over their arms. Immediately after this, the military and police were withdrawn from Peshawar; from 25 April to 4 May the city was in the hands of the people.’ (Palme Dutt: India Today, 1940)

At Sholapur in Bombay, the workers took over the administration for a week. Under Labour’s direction, the response of the government was brutal, creating a condition akin to martial law. Congress was banned in June, and Gandhi arrested. In the 10 months up to April 1931, between 60,000 and 90,000 people were arrested. Physical terror was the norm: between 1 April and 14 July alone, 24 incidents of firing had left 103 dead and 420 wounded; by the end of June, the RAF had dropped over 500 tons of bombs in quelling the disturbances.

GANDHI AND ‘THE ALTERNATIVE’

The Simon Commission reported in June 1930, offering no significant concession, merely fuelling the anger. In an effort to break the impasse, Labour convened a ‘Round Table Conference’, inviting representatives from the three British parliamentary parties, some Indian merchants, industrialists and landowners and various feudal puppets from the Indian princely states. Opening it in January 1931, MacDonald declared that ‘I pray that by our labours, India will possess… the pride and the honour of Responsible Self-Government’, an offer which committed the government to nothing. It was however enough for Gandhi; in March he persuaded Congress first to call off the mass campaign for a few petty concessions, and then to participate in the Conference it had sworn to boycott. He demanded no preconditions about self-government or home rule, only that the oppressive ordinances were to be withdrawn, and prisoners released — except those guilty of ‘violence’ or ‘incitement to violence’, or soldiers guilty of disobeying orders. This formula allowed Labour and Gandhi to exclude the Meerut detainees, a group of Sikh revolutionaries who were forthwith hanged, and 17 soldiers from the Garwhali Rifles, who were given severe sentences. With that, Gandhi was released to attend the Round Table Conference, a charade that continued for a year without resolution. As a contemporary communist wrote: ‘Hanging, flogging, slaying, shooting and bombing attest the efforts of parasitic imperialism to cling to the body of its victim. The Round Table Conference beside these efforts is like the ceremonial mumblings of the priest that walks behind the hang-man.’

There were sound reasons for Labour’s intransigence: the tribute from India ran at £120 million to £150 million per annum. As the Manchester Guardian pointed out in 1930: ‘There are two chief reasons why a self-regarding England may hesitate to relax her control over India. The first is that her influence in the past depends partly upon her power to summon troops and to draw resources from India in time of need [such as £180 million in gold the British government unilaterally removed from India to bolster sterling between October 1931 and March 1932] … The second is that Great Britain finds in India her best market, and she has £1,000 million of capital invested there.’

A Naesmith, Secretary of the Weaver’s Amalgamation, the largest textile union in Britain, echoed this view from the standpoint of the interests of the labour aristocracy when he told a mass meeting ‘they desired to see India and her people take their rightful place in the community of nations, but not at the expense of the industrial and economic life of Lancashire and those dependent on it.’

It had needed a Labour Government to re-establish British control over India. There is no more savage indictment of Labour than in its crushing of the Indian struggle of 1928-31. Under a fog of democratic phrases, it acted savagely. It destroyed any chance of the Indian working class playing a significant role in the Indian liberation movement, which from then on became the play-thing of different bourgeois interests. In a debate in 1930, an Independent Labour Party MP, WJ Brown, made a prophetic point when he told parliament: ‘I venture to suggest that we should regard it as a cardinal feature of British policy to carry Gandhi with us, for if we do not, we have to face the alternative to Gandhi, and that is organised violence and revolutionary effort.’

Those wishing to learn more about British rule in India can do no better than read India Today, by R Palme Dutt, Left Book Club, 1940. This is still widely available in second hand bookshops and public libraries.

In the second part of this article, Robert Clough traces the course of the struggle from 1931 to 1947.

Cotton exports destroyed

Between 1815 and 1832, the value of Indian cotton exports fell from £1.3 million to £100,000. In the same period, the value of English cotton imports into India rose from £26,000 to £400,000. By 1850, India, which had for centuries exported cotton to the world, accounted for one quarter of all British cotton exports. The population of Dacca, centre of the cotton industry, fell from 150,000 to 30-40,000. In 1797 exports of Dacca muslin amounted to 3 million rupees; by 1817 they had ceased altogether. Such was the impact of the tariffs imposed on Indian cotton imports. Without them there would have been no English cotton industry.

Deaths through famine in India:

1800-25 1 million 1

1825-50 0.4 million

1850-75 5 million

1875-1900 15 million

The 1931 census revealed the true nature of private ownership of the land. 4 million landlords owned 75 per cent of the land; one third of them owned 70 per cent of all arable land. 66 million tenant-cultivators owned the remainder, whilst 33 million were landless labourers. In the Punjab, a survey of 27 farms showed that the landlord took 82 per cent of the produce. In Bengal, at a time when the tax revenues were £3 million, the zemindars or landlords collected £13 million. Between 1911 and 1940, total peasant indebtedness rose from £225 million to £1.2 billions so that ’indebtedness often amounting to insolvency, is the normal condition of Indian farmers’ (The Problem of India, p41, Shelvankar, Penguin, 1940).

Annual tribute

Palme Dutt calculates the annual tribute from India to Britain in the twenty years to 1940 as averaging £135 million to £150 million – over £5 billion in today’s money. In 1933, British investment totalled some £1,000 million, about one quarter of all British foreign investment. The highest wages at this time were some 6 to 7 shillings a week; for women they could be below two shillings. This compared with an unskilled wage in Britain of 30 shillings, and a skilled wage of £4.

Princely states

LF Rushbrook-Williams in the Evening Standard 28 May 1930 on the princely states: ‘The situations of these feudatory States, checkerboarding all India as they do, are a great safeguard. It is like establishing a vast network of friendly fortresses in debatable territory. It would be difficult for a general rebellion against the British to sweep India because of this network of powerful loyal Native States.’

Gandhi: anti-working class

Gandhi’s thought, expressed to delegation of landlords in 1934:

‘I shall be no party to dispossessing the propertied classes of their private property without just cause… You may be sure that I shall throw the whole weight of my influence in preventing a class war… Supposing there is an attempt unjustly to deprive you of your property you will find me fighting on your side.’