Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No 138 August/September 1997

After 155 years of British occupation, Hong Kong finally returned to Chinese sovereignty on 1 July. JONATHAN COHEN reflects on the former colonial outpost of British imperialism.

Hong Kong was swarming with journalists. Many of the western reporters were, of course, scouring the city to find people opposed to or at least worried about the handover, but were largely disappointed. In fact, the change was welcomed, or at least accepted, by the great majority of Hong Kong’s people, 98 percent of whom are ethnic Chinese. In the rest of China, Hong Kong’s return was greeted with ecstatic nationalistic celebrations, marking the end of a century and a half of humiliation at the hands of the imperialist powers.

150 years of colonial rule

Hong Kong was stolen from China in three stages. First, in 1841 during the First Opium War, British Naval Captain Charles Elliot seized Hong Kong island. The next year, China was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanking, agreeing, amongst other humiliations, to cede Hong Kong to Britain, supposedly as a safe place to repair ships. Its real function was as a base for opium trading and for controlling the Pearl River delta and China’s southern coastline to back up future British aggression. Second, following the Second Opium War (1856-58) Britain forced China to cede the Kowloon peninsula. Finally, in 1898, Britain made China grant it a 99-year lease on the much larger New Territories and outlying islands.

In 1911, China’s weak and rotten Qing Dynasty was overthrown by revolutionary forces and the Republic of China (ROC) was founded. ROC founding father, President Sun Yatsen, declared all the treaties signed with imperialist powers to be unequal ones signed only under coercion, which China did not recognise. At the Versailles conference following the First World War, China applied for Hong Kong and other concessions to be returned but the appeal fell on deaf ears.

During the Second World War, Hong Kong suffered its darkest days as it was occupied by the brutal Japanese army for three and a half years. After Japan’s surrender, despite protestations by China’s President Chiang Kaishek, Hong Kong was returned not to China, but to Britain.

Following the overthrow of the by then hopelessly oppressive and corrupt ROC by the communists and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the new government in Beijing declared the unequal treaties to be invalid and vowed to take Hong Kong back at ‘an appropriate time.’

China became militarily strong enough to take Hong Kong back by force, but it never did. The main reason for this was China’s need to break out of imperialist-imposed isolation. With its colony of Hong Kong right on China’s doorstep, Britain had no choice but to deal with the communist authorities in China. Thus Britain was the first of the major capitalist countries to recognise the PRC, while others such as France only began to do so over a decade later, with the USA holding out for over 20 years.

In the wake of China’s civil war of 1946-49, Hong Kong had vast numbers of refugees living in sprawling, fire-prone shantytowns. To make matters worse, in 1951 the USA organised a UN embargo against China, threatening to destroy Hong Kong’s livelihood as a trade gateway to the mainland. To find employment for the refugees and achieve a new source of income, the British decided to industrialise Hong Kong. Hong Kong-made products such as textiles, clothes and toys enjoyed low-tariff or tariff-free access to the markets of Britain and other Commonwealth countries until Britain joined the European Common Market in 1973. Hong Kong’s access to these markets provided the conditions for its take-off as an industrial city. At the same time, its industrialisation and growing population made it ever more dependent on China for food, fuel, raw materials and especially for water. If Hong Kong is the goose which lays the golden eggs, then China is the farmer who feeds it. If Britain were to get its share of the eggs, it would have to play ball with China.

Thanks to socialist planning, China had built up a modern transport and power infrastructure and a strong heavy industrial base. Starting from the early 1980s, the Chinese government started encouraging foreign investment in order to obtain the technology and capital necessary for launching an economic take-off from this base. Hong Kong capital has spread into Shenzhen, the Pearl River Delta and other parts of China, where labour and land are cheaper and more plentiful. Hong Kong itself has become deindustrialised, entering the third phase of its development as a financial and trading hub. In the process, Hong Kong’s per capita gross domestic product has surpassed those of Britain, Canada and Germany.

‘An appropriate time’

Visiting China in 1982, British Prime Minister Thatcher suggested to Deng Xiaoping that Britain’s lease on the New Territories could be renewed after it ran out in 1997. Deng’s response was that China had said long ago that it would take Hong Kong back at an appropriate time, and that 1997 would indeed be an appropriate time to take back not only the New Territories; but Kowloon and Hong Kong Island as well. Thatcher had to grudgingly admit that China was calling the shots, and set about negotiating to get the best deal for British interests after 1997. The outcome was a promise from China that Hong Kong would remain basically unchanged for the first 50 years after its return, retaining its capitalist economy and British-style legal system. This is the concept known as ‘one country, two systems’, which had originally been formulated as a basis for reuniting Taiwan with the mainland. Had China not made this promise, virtually all Hong Kong and foreign capital would have left the colony, along with many of its wealthiest and best qualified residents, leaving China with an empty shell to take back.

Throughout the 1980s, Britain and China were cooperating well on preparations for the handover. The hitches started to come in 1989. Following the political upheavals which culminated in the Beijing rebellion in June of that year and its bloody suppression, Britain perceived the Chinese government as being in a weak position, and started pushing its luck. Governor David Wilson announced plans for an enormous project to build a new international airport without consulting the Chinese side. The costs of the project would be so vast that it would leave Hong Kong in serious financial difficulties by the time China took over. It is not hard to guess which country was going to get the cream of the lucrative construction contracts. At the same time, the British started making changes to the political system which were in breach of what had been agreed with China. Alongside the formation of political parties, the number of seats in the Legislative Council that were elected began to be increased, although the Council did not gain any more power, and all legislation was still subject to veto by the British-appointed governor.

Had Britain really cared about democracy in Hong Kong, it would have introduced elections some time in the first 149 years of its occupation instead of the last six. The real intention was clearly to make Hong Kong as difficult for China to absorb as possible.

British Governor Chris Patten’s trouble-making lasted right up to the last few days of his rule, as he tried to insist that China could not start moving armed troops into Hong Kong until after the midnight handover. As if Britain’s troops were going to vanish instantly at the point of midnight: There is no city in the world of the size and importance of Hong Kong which does not have armed forces stationed in it.

Assessing Britain’s role

Can Britain’s role be seen as positive? If we confine our vision to Hong Kong alone, then the answer is yes and no. On the one hand, the public transport system is great, traffic runs smoothly, the streets are clean and most people abide by the law without coercion. On the other, the mafia-like triad gangs have never been eliminated and drug addiction, prostitution and illegal gambling remain serious problems. On the one hand, Hong Kong has achieved great wealth. On the other, it is very unequally distributed. Among the population of six million, one million low-paid workers and their families live in dwellings that average more than seven persons per room.

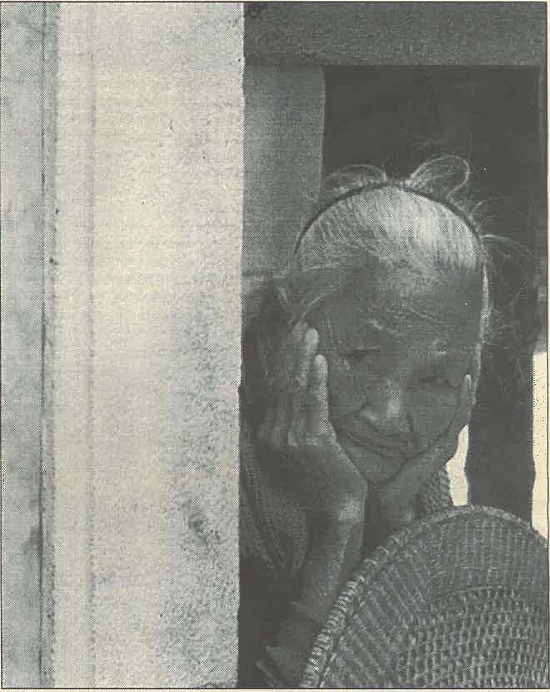

Then there are the ‘cage people’, mostly elderly men, who live in steel-mesh cages stacked two and three high, each only big enough for a mattress. These cages fill decaying slum buildings. Many of the over 10,000 ‘cage people’ have lived this way for decades. Another half-million are either homeless or live as squatters in shacks and makeshift dwellings on the outskirts of the sprawling urban landscape.

Nevertheless, the whole purpose of Hong Kong from the outset has been for exploitation. Quite simply, why else would you want a colony? Imperialism is quite capable of looking after a particular area or population or part of a population in order to achieve domination and exploitation on a wider scale. Look at Ireland for an obvious example. Hong Kong served British imperialism as a base for the barbaric pillage of China during the opium wars. It was a base for Britain’s decisive military intervention against the gigantic, progressive Taiping Rebellion in the mid 19th century, and against the anti-imperialist Boxer Rebellion which coincided with the Boer War. It was the guardpost for Britain’s ‘sphere of influence’ in China, which swept all the way from Guangdong and Shanghai in the East to Tibet in the West. While Britain may boast of the numbers of refugees the colony absorbed, it must be pointed out that Britain bore considerable responsibility for causing the poverty, disorder and war from which they were fleeing.

The radars and aerials which bristle from almost every available mountaintop in Hong Kong testify to its continued role as an international spy base after the Second World War. The colony was also a key site for ‘rest and recreation’ (go-go bars and prostitution) for British, US and other imperialist armed forces during the Korean and Vietnam wars and on up to the present day.

A key base like this is not to be maintained by repression alone. Social order, stability and a substantial layer of loyal natives are also required. Britain was challenged by resistance many times during its long occupation. Most outstanding among these were the long general strikes, initiated by dockers and influenced by the Chinese Communist Party, which paralysed Hong Kong in 1922 and again in 1925-26, as well as the anti-British strikes and riots of 1967 in which 51 people were killed and hundreds more wounded or arrested. In order to maintain its grip on the colony, Britain was forced to make concessions, each time. In the face of mass popular protest, it was forced in the 1970s to set up the Internal Commission Against Corruption to deal with rampant corruption in the police force and other sectors of the colonial government. Despite Hong Kong’s reputation as a dog-eat-dog arena of pure capitalism, efficient social services and some elements of a welfare state have been introduced in recent years to prevent the social upheavals that would arise if too many of the people were living in abject poverty.

When we communists study the present, we look to the past to understand it better. When we study a city, we look at the whole country, and when we study a country, we look at the world. We see both the wood and the trees that grow in it. That is why, while recognising that the British have created some things in Hong Kong which are worth preserving, we condemn British colonialism without reserve and warmly welcome Hong Kong’s reunification with China.