Since 25 August, almost 430,000 Rohingya, 1,400 of them orphaned children, have fled Myanmar amid some of worst violence seen against them. A further 30,000 members of other small minority groups have also been displaced, with around 214 villages completely razed and still smouldering; flames and smoke visible from neighbouring Bangladesh. After an attack on an army base and police posts by Rohingya militants, Myanmar state officials reacted with massive force, beating and firing at unarmed Rohingya children, women and men, and using rocket launchers.

Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled Myanmar; a majority to Bangladesh, others to Malaysia, India, Thailand, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Mines laid by the Myanmar army lie along the two main land crossings between Bangladesh and Myanmar and have caused numerous casualties. Bangladesh has continuously returned many of the Rohingya, and Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina recently called for ‘safe zones’ in Myanmar to keep returning them to, despite many of the refugees being orphaned children. Many are pushed back or detained at the border between the two states. Numerous Rohingya have drowned in surrounding seas whilst trying to access neighbouring shores on tiny, overcrowded boats. Recent monsoons across South Asia have been making it all the more dangerous for Rohingya refugees and even those fortunate enough to have survived so far face horrendous conditions at camps. Indian border forces have been using stun grenades containing chilli spray to deter Rohingya entering India. On 19 September Theresa May, responding to criticism of Britain’s complicity with genocide, promised to ‘stop all defence engagement and training of the Burmese Military’.

Mainly Muslim with a Hindu minority, the Rohingya, historically known as Arakanese Indians and with a population of roughly 1-1.3 million, can trace their history of living in the Arakan region, now known as Rakhine, back to the 8th century when Arab merchants reached the area through a southern branch of the Silk Road and the Bay of Bengal and settled there.

The region remains geo-strategically important today, with Myanmar estimated to possess 3.2 billion barrels of oil and 18 trillion cubic feet of natural gas reserves. This would place Myanmar fifth in terms of nations with proven reserves.

Global powers are competing for strategic influence in Myanmar and access to these huge fossil fuel resources. The army of Myanmar uses religious and ethnic differences to crush opposition to international investments. US and European oil companies including Shell, Total, Statoil, Chevron and Conoco Phillips have been awarded contracts, with many of them being production-sharing initiatives for the Rakhine Basin. The Rakhine region is also important for China. Chinese oil and gas pipelines across Myanmar, crossing Rakhine – part of China’s massive ‘One belt, one road’ trading and infrastructure strategy – aim to ensure that fuels from the Middle East, Africa and elsewhere can be transported to eastern China without having to pass through the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea where they could be vulnerable to a US blockade if rivalry and conflict grows. The building and operating of these pipelines, which has included widespread environmental damage, have met local opposition along their length. The US and its allies are keen to disrupt these pipelines, and may try to use the Rohingya crisis as a way to undermine Chinese power in the region.

Anti-Arakanese Indian violence dates back to the 18th century when the Konbaung Dynasty 1785 conquest of Arakan forced 35,000 people to flee to Chittagong in present-day Bangladesh. By the time Britain occupied the region in 1824, Arakan had been left with a hugely diminished population owing to the executions of thousands of men and wide scale deportations carried out by the Bamar, the dominant ethnic group of Burma or Myanmar.

Over the 124-year British occupation, British policy placed no international boundaries between Arakan and Bengal and no restrictions on migration and, from the early 19th century, thousands of Chittagongian Bengalis settled in Arakan and wider Burma with further waves of migration in the following years, owing to British demands for cheap labour. Many Arakanese Indians who had been deported prior to British occupation returned to Arakan. This migration was met consistently met with outrage amongst Bamar and gave rise to Burmese nationalism, becoming the focus amongst grassroots movements and causing riots from 1930 onwards.

In 1938 the riots escalated, gaining further momentum with the onset of the Second World War, with clashes between northern Arakan villagers and Burmese nationalists. In 1942 the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Burma and the British forces fled, having prepared for their retreat by arming the Arakanese Indians. A power vacuum led to intense violence between groups loyal to Britain or Japan and in the Arakan Massacre of 1942 some 40,000 Muslims and about 20,000 Burmese Buddhists were killed. Japanese Army forces tortured, raped and executed Arakanese and Indian Muslims and deported thousands to India. Over 60,000 Muslims, Indians and Anglo-Indians fled towards Bengal and present-day Bangladesh.

When Burma declared independence from Britain in 1948, the Rohingya were recognised as an indigenous ethnic nationality and therefore citizens of Burma, with representation in the Burmese Parliament. This lasted until the 1962 coup d’état by the military Junta revoked this recognition. The 1974 constitution downgraded their status further, and the 1982 Citizenship Act did not include Rohingya as one of 135 national ethnicities of Burma, denying their citizenship and effectively rendering them stateless. As a result, Rohingya face enormous hurdles accessing healthcare, education and employment and are subjected to restrictions on marriage and a two-child policy. The infant mortality rate is 224 per 1,000 live births. In what can only be described as ethnic cleansing they endure forced labour, forced eviction and confiscation of land and property, rape, torture, arbitrary taxation, false arrest and imprisonment, and execution. Passes are needed for travel and exorbitant costs combined with restrictions on employment mean freedom of movement for Rohingya is non-existent. There is only one university in Rakhine’s capital Sittwe and Rohingya students can only study through distance learning.

Nationwide civil unrest saw an election called in 1990 and the Rohingya-led National Democratic Party for Human Rights won four seats. The party was banned in 1992 and Rohingya politicians, such as Shamsul Anwarul Huq, who was sentenced to 47 years in prison, were gaoled to prevent them from contesting elections. Myanmar’s now de facto leader Aung San Sui Kyi won that election with the National League for Democracy. However, Sui Kyi was already under house arrest and the results were nullified. Offered freedom by the junta on condition she leave Myanmar never to return, she refused and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 for her work ‘defending human rights’.

In November 2010 Aung San Sui Kyi’s house arrest ended and in 2012 she announced her intention to run for presidency in the 2015 elections. As she was barred under the 2008 constitution from presidency on the account of being the widow of and mother to foreigners, President Htin Kyaw created the position of State Counsellor, the equivalent to Prime Minister for her.

Long heralded by the west as a beacon for democracy, she refuses to acknowledge the genocide of Rohingya and does not accept their Burmese ethnicity, claiming in a speech on 19 September that she ‘does not know why Muslims were fleeing’. The international ‘war on terror’ is used to justify anti-Muslim hatred in Myanmar.

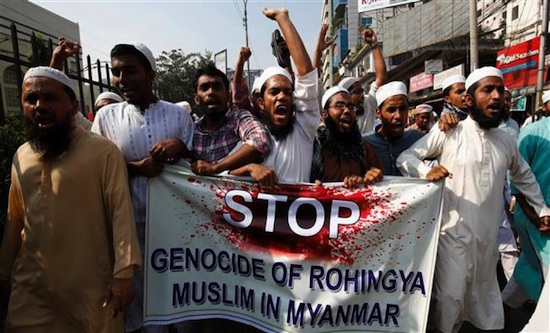

Protests have taken place around the world, with condemnation of Myanmar’s government growing. Hundreds of protesters gathered outside the Myanmar embassy in London and thousands marched in the Pakistani city of Karachi on 10 September. Tens of thousands marched through the Russian city of Grozny on 4 September and over 10,000 marched in the Bangladeshi capital Dhaka on 19 September, with similar protests taking part in Malaysia and Indonesia. The Rohingya are victims of ethnic cleansing whipped up by the struggles of major capitalist powers over resources, investments and strategic control. Calls for western intervention put forward at some of these demonstrations can only make things worse for the Rohingya.

Nazia Mukti