FRFI 167 June / July 2002

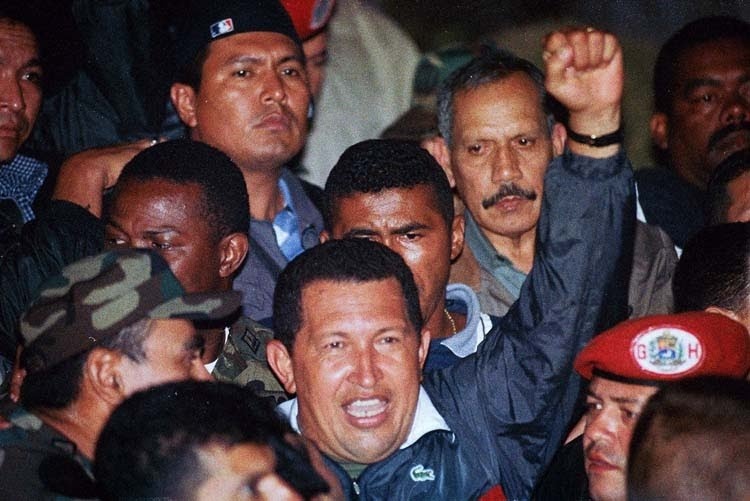

In a counterblow that stunned US imperialism, the coup it had sponsored against the popularly elected government of President Chavez, was quickly broken by the strength and determination of the Venezuelan working masses. On the weekend of 11-14 April, after more than ten months of continued planning, a plot to remove not only President Chavez but every single democratic gain made in Venezuela over the last four years was shattered by the resistance of the poor and their democratic allies. In Caracas, Venezuelans marched in their thousands to the Presidential Palace forcing the cancellation of the inauguration of the plotters’ ‘interim’ Cabinet, effectively placing them under citizen’s arrest. The masses announced that they would remain until the elected President, Hugo Chavez, was returned to the Palace. With loyal troops actually waiting in the Palace basement corridors, the chief of the paratroop division then ordered the trapped would-be dictator to release President Chavez .

In the following account one issue stands out. Venezuelan oil is central to the strategic programme of US imperialism. The USA needs this oil to breach the OPEC quota agreements. Privatisation of the country’ s oil resources would safeguard their strategy of global plunder. ALVARO MICHAELS reports.

Thursday 11 April: murder

The coup was organised on the back of a strike by oil executives and managers at the state oil company PDVSA, called to reject government control of the huge state oil corporation. It led to a political demonstration by the middle class and well-paid oil workers against the State President on 11 April. The demonstration was set up by a clique preparing a coup.

This clique consisted of the following:

• the Chamber of Commerce leadership headed by Pedro Carmona. Many in the business community, eg in textiles, opposed the government because of a proposed 20% increase in the minimum wage;

• the CTV oil union leadership which had directly disobeyed new laws requiring fair and free elections for union leaderships;

• instinctively reactionary, older and senior sections of the army dependent on US aid;

• the Catholic Church leadership, offended by the new constitution;

• the richest business leaders, opposed to any real democracy, including Gustavo Cisnaros, a media and drinks mogul, billionaire and a fishing partner of President Bush.

These forces were anxious to privatise industry, especially the state oil industry, whereas Chavez had promised to halt privatisations. On 11 April, as the demonstration prepared to set off, Venezuelan political and business leaders met privately, in true plutocratic style, at the Cisneros mansion, to welcome the new US ambassador. Cisneros’ TV company, Venevision, promised non-stop coverage of the demonstration that afternoon.

The demonstration, headed by governors and mayors opposed to President Chavez, demanded his resignation. The five TV chains, including that of Cisneros, plus Radio Caracas Television, Televen and Globovision – upset over having to pay taxes like any other business for the first time in their history – were running free advertisements every ten minutes inciting their viewers to join the march. With the 40,000-member CTV oil workers union, the National Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Catholic Church hierarchy pulling out all the stops to create the illusion of a popular revolt, they managed to get about 150,000 people onto the streets of Caracas. The stock market leaped by 10%.

Diverted without warning by the organisers from its route to the National Oil Corporation headquarters, the demonstrators marched to the Presidential Palace – Miraflores. There they faced a smaller pro-Chavez demonstration which had been mobilised at the last minute. The pro-Chavez National Guard, although provoked with sticks and stones by demonstrators at the front of the anti-Chavez march, kept the two groups apart.

Trained provocateurs then fired shots from a rooftop into the pro-Chavez group standing by their platform. The first two to be killed were a legal secretary and an archivist, both of whom worked in the Presidential building. A 10-year-old girl was then taken away, fatally injured. Snipers aimed more shots at the ‘Chavistas’ many of whom took shelter behind the Palace wall. In the subsequent shooting, 17 people were killed (most were shot from high angles into the head ) and over 100 were wounded in the confused crossfire that broke out between other armed opposition gunmen and a few government supporters. Eventually three snipers in civilian clothes were arrested. The attempt by Chavez himself to broadcast an explanation on television was then blacked-out. A group of ten army and navy generals arrived at the Palace headed by General Efrain Vazquez. (Over 80 senior officers participated in the coup.)

Friday 12 April: shock

At 3am on Friday a tearful Environmental Minister, Analisa Osorio, emerged announcing ‘He’s under arrest’, along with Vice President Cabello. The military junta that had arrested and imprisoned the President at gunpoint without charge, installed National Chamber of Commerce and Industry chairman, oilman, and number-one coup leader Pedro Carmona as President. Carmona had been waiting at Gustavo Cisneros’ Venevision TV station where he had met with other conspirators the previous afternoon. From there he drove to the Presidential Palace to take up his post. Later Cisneros and other media executives arrived at the Palace in limousines, where he was called twice from Washington by Otto Reich, assistant US Secretary of State for ‘hemispheric’ affairs.

Radio and television immediately announced the resignation of Chavez and began broadcasting pro-coup messages: ‘Venezuela is finally free’ was the banner across all private TV channels. The government went into hiding. Interior Minister Rodriguez was hunted to his home and arrested. Many fled for their lives. Pro-Chavez journalists were beaten and harassed by the Technical Judicial Police on the pretext of searching for arms. A mob of 500 assaulted the Cuban embassy which sheltered four supporters of Chavez. A witch-hunt began. The media kept repeating footage of the swearing-in ceremony of the ‘interim President’, which was followed by images of tranquil streets. AP, Reuters, the New York Times, CNN and many other English-language media repeated the lies again and again that the gunshots had come from armed Chavez supporters. And White House Press Secretary Ari Fleischer claimed that Chavez ordered the shootings. The arrested snipers were released by Carmona’s clique the next day.

Among Carmona’s first acts in the ‘Transitional Junta Decree’ on Friday was to declare the 1999 Constitution void, promising to restore the pre-1999 bicameral system. He abolished the elected National Congress, disbanded the constitutionally-established Supreme Court, delayed new elections up to a year and changed the name of the country from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela to the Republic of Venezuela. He dismissed the President and magistrates of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ), Comptroller, Attorney General, Official Ombudsman and members of the National Electoral College (CNE) and reinstated ex-General Lameda as President of PDVSA. The decree also suspended 48 laws passed constitutionally by the Chavez government and Congress in 2001. The response of the western mass media, including the ‘liberal’ New York Times, was to applaud these steps as measures necessary to preserve and enhance ‘democracy’ in Venezuela. The White House blamed Chavez for ‘undemocratic acts’ and gave tacit backing to Carmona. This was in sharp contrast to the dramatic threats made by US President Clinton against the soldiers and indigenous peoples that overthrew the pro-US government in Ecuador in January 2000.

Thus, in the name of stopping an ‘autocrat’, ‘dictator,’ ‘authoritarian’ (epithets used by almost all the western press) the coup installed a real, unelected dictator – Pedro Carmona. He began a house-to-house search for cabinet members, congressmen and political leaders. ‘We cannot allow a tyrant to run the Republic of Venezuela,’ said Navy Vice Admiral Hector Rafael Ramirez, at the precise moment that he was installing a tyrant to run the Republic of Venezuela. The PDVSA now announced that it would not maintain the OPEC quotas, and immediately suspended oil exports to Cuba! The price of oil fell. Just what the USA wanted.

Saturday 13 April: workers strike back

A government was named that included several members of the ultra-right-wing Catholic organisation, Opus Dei, but key military and trade union figures were excluded. This created an immediate split among the plotters. Alarmed at the precedent being set, other Latin American leaders now refused to recognise the new government. Mexico, Brazil, Argentina and others condemned the coup. The 19-nation Rio group of states declared its opposition. On Saturday 13 April, the US Ambassador met Carmona, passing on instructions from Reich to reinstate the National Assembly, since this violated the Constitution.

By Saturday morning thousands of workers had gathered outside Fort Tiuna, where Chavez was held, demanding his freedom. Uncertain what to do, his captors flew him to a navy base at Turiamo. The most crucial turning point of all was when rank-and-file soldiers and officers at the nation’s largest army base in Maracay, soon joined by troops in nearby Valencia, rejected the military junta and began the counter-coup. Later the Speaker of the National Assembly rejected the dictator Carmona’s decree abolishing the elected legislative branch of government.

By that afternoon huge protests had erupted in the slums of Caracas – los Ranchos – against the dictatorship. The five big TV chains had made a decision not to report demonstrations against Carmona. Huge crowds had surrounded the Palace, demanding the return of Chavez. ‘The only weapons we have are lessons we give to the poor – to help them fight for their rights’ (Yarguin, a farmer, quoted in the Caracas News). Several TV stations were taken over by Chavez supporters and the office of the anti-Chavez Mayor of Caracas was attacked. By 3pm, several Chavez deputies had returned to the Palace and a dozen people who were working for the interim government had been taken to a room in the basement for their own safety. Reports came in from around the country, barracks by barracks, that the military was rebelling against the coup. The television continued to broadcast a steady diet of soap operas, saying nothing about the huge mobilisation, which was now making a deafening noise outside. In the streets of virtually every city and town in Venezuela, at least a million poor ‘came down from the hills’, as the day before the coup Chavez had predicted that they would.

In Caracas, Carmona’s troops began firing on crowds indiscriminately. Morgues and hospitals filled with dead and wounded civilians – 49 dead and 332 wounded. Rank-and-file soldiers throughout the country broke ranks with the officers, reclaiming the Presidential Palace, and forcing the senior military commanders to backpedal. Then at 6.40pm a military junta leader admitted on the radio that Chavez had never resigned. The military second-in-command announced on TV that he was taking charge of the Palace until he saw proof of Chavez’s resignation.

By now Carmona had left Miraflores for Fort Tiuna. He went on TV to announce a reversal of his unpopular decrees and then resigned in favour of the real Vice President Cabello and was then arrested by DISIP, the political police. Then came the news that Chavez had been freed and was taking a helicopter to Miraflores. The crowds went wild. On Monday the stock exchange fell by 8.14%. The oil price rose again.

Never before in modern times has an elected President been overthrown by military commanders, his successor inaugurated, and then returned to power by a popular uprising – all in the space of a few days.

In Washington by Sunday 14 April the OAS, in a statement watered down and then signed by the USA in order to retain ‘credibility’, condemned ‘the alteration of the constitutional order’, invoking the new ‘Democratic Charter’ approved in Lima in September 2001.

How oil wealth is removed from Venezuela

Low oil prices mean Venezuela loses its resources. With higher prices imperialism requires an indirect method of removing its wealth. The rise in oil revenues in 1999 and 2000 brought a rising exchange rate. Usually, the bolivar drops 7% a year via a crawling band arrangement with the dollar. From early 1999 to 2000 oil prices rose from $10 to $30 a barrel. By September 2001 the bolivar was some 50% overvalued in terms of the country’s overall economic capacity. Anxious that devaluation would rob them of the dollar rate for the bolivar, speculators began to buy dollars with bolivars so they could move funds abroad. In the first half of 2001 $800m fled the country. Venezuela’s international reserves fell 25% by September. To keep its foreign currency reserves, the state began paying speculators 30% interest to keep their bolivars and increased its discount rates to commercial banks to 37%. On 10 September a ban on currency sales to companies based outside the country was introduced and domestic banks were told to hold a larger reserve ratio to restrict lending. This also increases the state’s own interest payments which have risen almost 200% in the last two years. Thus under the existing arrangements Venezuela loses whether oil prices are high or low.