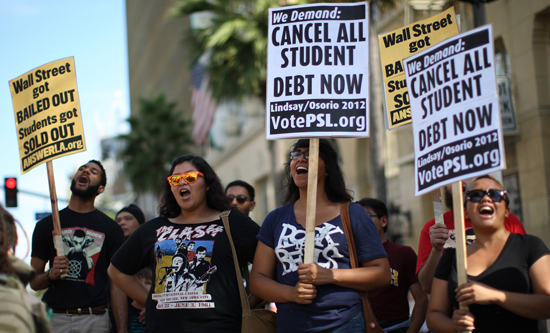

Owe the bank £100, the old saying goes, and you have a problem; owe the bank £1 million and the bank has a problem. In the US almost 40 million people owe a total of $1.16 trillion in student loans. Since British capitalists have decided to follow their US counterparts onto the same slippery slope of financing higher education privately, it is worth having a closer look at the contradictions in this system.

Loans in the US

Student loan delinquencies are rising fast: loans more than 90 days delinquent are 4.3% of all consumer debt and 3.1% for mortgages: for student loans, the rate is 11.3% and increasing. When we take account of the fact that half of all these loans are in deferment, grace periods, or forbearance – in short, not in the repayment cycle – the delinquency rate more than doubles. With some putting it as high as 30%, it is clear there is a problem.

The causes of repayment problems are quite simple. Students take out loans, then graduate and find that they cannot get a reasonably paid job in the stagnating economy, and student loan repayments are among the first items young people forego as they are pushed into relative poverty. A nominal $25,000 loan at typical interest rates, with deferment, including fees and commissions can end up earning SLM (known as Sallie Mae) $74,126, costing the student nearly three times the face value of the loan. Further, in the event of delinquency, debt collectors are allowed to tack on a 25% collection fee and a 28% commission, bringing the total owed by the former student to $113,413. With austerity, school fees have to rise to make up the shortfall in public funding, so the average level of student loan will increase, compounding the problem.

In the US, where student loans have been the norm for a considerable time, the vast majority of student loans are taken from the Federal Government. Borrowing at very low rates just above 1%, because the government is expected to stay solvent, the Department of Education currently makes loans at about 6.8% to students through a number of private corporations – the largest of which is Sallie Mae. Sallie Mae is a cousin of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, the ‘Government Sponsored Enterprises’ which were at the centre of the mortgage crisis a few years back (see FRFI 204 – August/September 2008). The resemblance is more than just the name: like Freddie and Fannie, Sallie Mae takes loans – student loans rather than mortgages – slices and dices them, and puts them in a parcel called a Student Loan Asset Backed Security, or SLABS. It then sells SLABS on to private investors. Asset Backed Securities were at the heart of the 2007-8 mortgage crisis, because their default rate was far higher than expected. While the student loan total of $1.16 trillion is dwarfed by the $8.1 trillion of mortgage debt, a 20+% default rate is clearly going to cause some unpleasant surprises for SLABS holders in the future, creating some stresses in parts of the financial system.

By securitising the loans into SLABS, Sallie Mae receives an immediate payment, instead of waiting years. Securitisation has enabled the US Department of Education to generate $101.8 billion in revenue between 2008 and 2013. In 2013, the amount was $51 billion or 2% of all federal revenue. From supposedly helping people enjoy higher education, the loan system has morphed into a source of government funding while incentives to reform it have evaporated.

Loans in Britain

George Osborne, the Chancellor, has already committed the British government to selling parts of the pre-2012 student loan ‘book’, ie the student loan portfolio. The superficial attractions of doing this are obvious: it will reduce part of the national debt, as well as bringing in extra revenue, helping the government to claim it is hitting deficit targets.

There are some problems with this rosy fantasy. There are a number of technical issues with the loans which mean that the exact return on them is indeterminate, making them very hard to price, or else to require continued government support. On pre-2012 loans – the ones which are candidates for sale – the interest rate is based either on bank base rate plus 1%, or on the cost of living. Both rates could vary significantly over the 30-year period of the loans, with the real possibility that the asset could return less than the rate of inflation. This makes it impossible for potential customers of the debt to know whether their purchase would be profitable or not. Also, the default rate is unknown – the relative novelty of these loans makes it impossible to do more than guess at the default rate over their lifetime, again putting a big question mark over their profitability. The simple solution to these is some sort of government guarantee to subsidise the loans. But in that case, the loans are no longer ‘off the book’ when they are sold, but a continuing obligation or ‘risk’ to be serviced and therefore still part of the national debt – which is supposed to be cut by their sale! This might allow some fancy bookkeeping which might look as if the debt has been reduced, but the continued real obligations will weigh on future governments. Currently the ‘Fair Value’ on the books obtained by some complex computer modelling is £33 billion, based on a face value of £54 billion – ie, it expects to receive only £33 billion in repayments. Already these models have been criticised as unrealistic.

This mess is just one of the delights resulting from trying to follow the road of American capitalism. Further joys which await future students include tangling with the debt recovery industry which is going to spring up as defaults rise and the number of outstanding loans swells. Another experience will be the emergence of private colleges, offering vocational training to desperate students, which are really just financial vehicles for private companies to leech off student loans. These have grown up across the United States. Their teaching is shoddy and curriculum inadequate to pass industry standard vocational certifications. If their students don’t leave with high academic scores, they will be guaranteed to be loaded up with student debt, immediately gobbled up by the colleges in fees and administrative charges. They quite deliberately target vulnerable groups who are poor and financially unsophisticated: minorities, single parents, welfare recipients. These parasitic corporations will dovetail nicely with the new government’s privatisation agenda which will want to encourage ‘competition’ from private ‘education’. The only real education they offer is a course in the viciousness of capitalism, which will leave them impoverished, exploited and deeply in debt.

Steve Palmer