‘The monster they’ve engendered in me will return to torment its maker, from the grave, the pit, the profoundest pit. Hurl me into the next existence, the descent into hell won’t turn me. I’ll crawl back to dog his trail forever. They won’t defeat my revenge, never, never. I’m part of a righteous people who anger slowly, but rage undammed. We’ll gather at his door in such a number that the rumbling of our feet will make the earth tremble.’

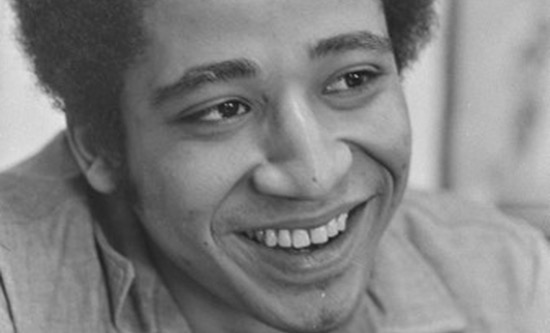

Fifty years ago, on 21 August 1971, George Jackson was murdered by wardens in San Quentin prison. He was just 29 years old, and had served 11 years of an indeterminate sentence, seven of them in solitary confinement, for the theft of $70 from a petrol station. Jackson was a revolutionary communist writing at a time of political ferment in the United States: its imperialist hegemony was being challenged in Vietnam, while at home the emerging capitalist crisis was driving resistance from the poorest sections of the working class, particularly black people faced with the daily reality of police brutality and deteriorating economic conditions. That movement was reflected in the prison struggle, in which George Jackson played a leading role. At the time of his death his contribution to the revolutionary struggle was widely recognised, and his murder inspired a wave of renewed protest, both inside and outside the prison system. Huey Newton, the leader of the Black Panther Party, described George Jackson as a hero whose ideas would live on. For Walter Rodney, he ‘served as a dynamic spokesman for the most wretched among the oppressed, and was in the vanguard of the most dangerous front of struggle.’ Jackson’s prison writings, Soledad Brother and Blood in my Eye, were described by the Trinidadian Marxist CLR James as ‘the most remarkable political documents that have appeared inside or outside the United States since the death of Lenin’.

George Jackson grew up in the black ghettoes of Chicago and was involved in petty crime from an early age. But in prison ‘I met Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Engels, and Mao … and they redeemed me.’ He joined the Black Panther Party in 1967. Jackson remained an active communist all his life, a tireless advocate of the need for the working class, in particular the black working class, to fight for socialism and their right to use revolutionary violence to do so. Although some parts of his theory need further development, especially in relation to imperialism and his characterisation of vicious US state racism as fascism, George Jackson’s writings provide vital lessons for the new resistance emerging in the United States against police racism and brutality and the triumphalist rise of a naked white supremacy that has never lain far from the surface of a nation founded on racist genocide.

‘The black reservoir of revolutionary potential’

Jackson understood that the capitalist system is at the root of racism, poverty, unemployment and oppression. It was only the form of oppression of the black working class that changed after the Civil War, ‘from chattel to economic slavery’ as black people ‘were thrown on the labour market to compete at a disadvantage with poor whites … all that has changed is the terms of our servitude’.

This economic upheaval created a black working class that will be a central component of any future revolutionary vanguard of the working class. ‘The principal reservoir of revolutionary potential in Amerika lies in wait inside the Black Colony. Its sheer numerical strength, its desperate historical relation to the violence of the productive system and the fact of its present status in the creation of wealth force the black stratum at the base of the whole class structure into the forefront of any revolutionary scheme.’

This force can serve as the catalyst for wider revolutionary change: ‘The impact of black revolutionary rage actually could carry at least the opening stages of a socialist revolution under certain circumstances’ – as long as the wider movement understands ‘the specter of racism’: ‘if we are ever going to be successful in tying black energy and rage to the international socialist revolution, we must understand that racial complexities do exist’.

‘New forms of struggle will arise’

The new movement must consciously break with the stale traditions, compromise and electioneering of the traditional left. The Civil Rights movement had ended formal segregation, but the raw experience of the black working class in terms of housing, education, employment, poverty and brutal policing had not changed. Inspired by the struggle of the Vietnamese people, black militias had arisen to defend black communities, most significantly the Black Panther Party, with its anti-imperialist and socialist agenda, community programmes and defence of the right to bear arms. Meanwhile, the traditional left movement – particularly the Communist Party of the USA – failed entirely to respond to the new conditions, refusing to recognise the specific nature of racial oppression. There was, Jackson wrote, an overwhelming need for a new movement. He quotes Lenin: ‘New forms of struggle … inevitably arise as the given social situation changes, the coming crisis will introduce new forms of struggle that we are now unable to foresee.’ In a pointed jibe at the old left, Jackson stresses that ‘there can be nothing dogmatic about revolutionary theory’.

It was, Jackson said, no longer plausible to put up a worker for election on a radical, ideal platform and, when they were defeated, hand out leaflets explaining how the system had failed. Today such a stance amounted to counter-revolution. ‘The history of the US – the blood-soaked urine-steeped essence of its being; the wreckage and demise of its human character under the wheels of a 200-year-old headlong flight with headless, frightened animals at the controls of a machine that has mastered them – allows for no appeal on a strictly ideological level … What is an honest election after the fact of monopoly capital?’ Those retaining illusions in the Democratic Party should take note. The traditional – and predominantly white – working class, ‘the proletariat’, is too compromised with the system: imperialism has created a layer ‘whose needs can be met by capitalism … [who] just simply cannot understand that they are existing on the misery and discomfort of the world’. Jackson understood that the US ruling class has been able to ‘co-opt’ and ‘neutralise’ large ‘degenerate sections of the working class, with the aim of creating a buffer zone between the ruling class and the still potentially revolutionary segments of the lower classes’. Thus imperialism has been able to ‘merge the economic, political and labour elites’ into ‘the greatest (reactionary) community of self-interest that has ever existed.’ Jackson calls for a rejection of ‘sterile, stilted attempts to build new unions … or elect a socialist legislature’.

Instead, black people in the United States, along with their allies ‘must enter the war on the side of the majority of the world’s people, even if it means fighting the USA majority’. The forces of revolution are those with ‘the least short-term interest in the survival of the present state’. ‘The outlaw and the lumpen will make the revolution. The people, the workers, will adopt it’. Such a movement will inevitably be anti-imperialist.

But equally the movement must beware black bourgeois elements who promote black separatism, and ‘attack the white left … who want to help us destroy fascism.’ They use ‘the tactic of [attacking] “white left-wing causes” to protect the bosses’ “white right-wing causes”’. They are ‘as much part of the repression, even more than the real-life rat-informant pig’. In a world where the sweatshop has displaced the plantation, ‘these are the new house n*****s’.

The vanguard party and revolutionary violence

‘The existence of a political vanguard precedes the existence of any of the other elements of a truly revolutionary culture’.

The movement must be led by conscious revolutionaries. It must develop beyond ‘the confused flight to national revolutionary Africa and beyond the riot stage of revolutionary Black America’. It must embrace ‘scientific revolutionary socialism’. To do so, it must be led by a vanguard party. To believe riots and spontaneous struggle are enough is romanticism: ‘Don’t think you don’t need ideology, strategy or tactics … It is not enough to be “a warrior”.’

Following Lenin, he is clear that revolution in a modern industrial capitalist society must entail the overthrow of all property relations. He takes on board the key lesson of the Paris Commune: ‘The prerequisite for a successful popular revolution is to totally junk the old machinery of state … a social revolution after the fact of the modern capitalist state can only mean the breakup of that state and a completely new form of economics and culture’.

In order to become ‘the gravediggers of capitalism’, the vanguard must understand the need to build consciousness through theory and education so the people accept the need for revolutionary violence. There are no ‘spontaneous revolutions’ – only those directed by a revolutionary vanguard. He pours scorn on the petit bourgeois slogan, ‘you can’t get ahead of the people’. From where else, Jackson asks, would you be leading? At the same time the vanguard cannot substitute itself for the masses. It must find out what they need and organise around those demands. ‘Revolutionaries manufacture revolution’. The need is urgent: ‘[it follows that] If a thing is not building, it is certainly decaying – that life is revolution and the world will die if we don’t do something about it … not on its own will it die, but rather because the forces of reaction have created imbalances that will kill it, the seeds of its own destruction’.

The monopoly capitalist or imperialist state is implacable. It will not willingly relinquish its vast power and immense privileges. It will seek to crush even the slightest flicker of resistance. Therefore any serious movement has no option but to embrace armed struggle alongside its political work. ‘As revolutionaries it is our objective to move ourselves and the people into actions that will culminate in the seizure of state power. Our real purpose is to redeem not merely ourselves but the whole nation and the whole community of nations from colonial-community economic repression’.

He points out that even the most limited self-organisation such as breakfast clubs will provoke the police to come in shooting on the flimsiest of pretexts. It is not idealistic or ultra-left to insist that we must develop forms of urban guerrilla struggle. Jackson wrote in the context of black communities being turned into police free-fire zones, and the brutal murder of black activists. Jackson is surely right to say, ‘If terror is going to be the choice of weapon, there must be funerals on both sides’.

The fire this time

The rising anti-racist and anti-imperialist movement of the 1960s and 1970s was drowned in blood and drugs. The FBI unleashed COINTELPRO to eliminate the Black Panther Party; dozens were killed and thousands imprisoned. Revolutionaries like Fred Hampton and George Jackson were assassinated. From 1971, under Republican and Democratic administrations alike, black communities were deliberately flooded with cheap crack cocaine to divide and criminalise them. Today, 38% of prisoners in the vast US prison system are black, despite representing only 13% of the population. It took a global movement of rage to secure the conviction of just one white police officer for the 2020 murder of one black man, George Floyd; yet in the first six months of 2021, 440 more black people were killed by police. Meanwhile, white supremacist militias target black and minority communities; voting rights for black people are being systematically undermined. State after state is criminalising the teaching of black history. George Jackson recognised that the crisis-ridden capitalist state is ruthless and compromise futile. Only a sustained and conscious struggle against capitalism and for socialism, led by a dedicated vanguard, can defeat it and create new conditions for human relations, governed not by the profit-motive but by the needs of all of humanity. ‘Black, brown and white are all victims together – at the end of this massive collective struggle we will uncover our new man…He will be better equipped to wage the real struggle, the permanent struggle after the revolution – the one for new relationships between men’.

Cat Wiener

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No 283, August/September 2021