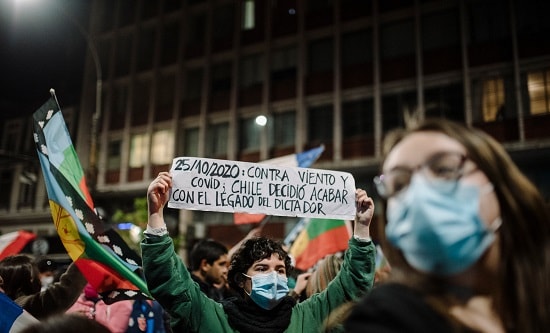

On 25 October millions of Chileans voted in a plebiscite to erase the legacy of Pinochet from the country’s Constitution. Two ballots were presented to voters. First, to approve or reject a proposal to rewrite the Constitution. Second, on whether those charged with writing a new Constitution be elected by a Convention with 50% directly-elected constituents and 50% MPs (Mixed Convention), or a Convention exclusively of directly-elected constituents (Constituent Convention). Despite the coronavirus pandemic, there was 50.9% voter turnout, slightly higher than the average turnout for parliamentary and presidential elections over the last decade. 5,884,076 votes (78%) approved a rewrite of the Constitution, 5,644,418 (79%) chose a Constituent Convention (CC), the vote for which will take place on 11 April 2021.

The current Constitution was written under Pinochet’s dictatorship in 1980 and it enshrines protections for neoliberal policies that put health, housing, education and pension in the hands of the private sector. Last year, on 18 October 2019, secondary school students jumped over metro station barriers in protest against a fare hike of 30 pesos (See FRFI 273). The violent police repression that followed ignited a tsunami of protests unseen since the days of Pinochet, shaking right-wing President Sebastián Piñera and his cronies into action. The people’s fury progressed into a general strike on 12 November 2019 which forced the Chilean ruling class to introduce their ‘Agreement for Peace’. The process toward a new Constitution was set into motion a month into the uprising.

The promise of the plebiscite lifted people’s expectations, but on close inspection it became evident that Piñera’s ‘Agreement’ had been engineered to limit the scale of change and furthermore protect his position as President. The newly-formed Command for a Free and Sovereign Constituent Assembly points out that the plebiscite was ‘a by-product of the popular rebellion in the streets’ and was ‘set as a trap by a government and regime powerless to stop its revolutionary fall by the direct action of the masses’ (La Izquierda Diario 27 October 2020).

The Agreement’s objective was to divert the movement into a safe electoral path that could be managed by Piñera’s government. It bans interference in international agreements which means that imperialist plunder of Chile’s resources such as copper and agricultural produce will be left intact, as will the private, market-based pension system; under-18s will not be allowed to vote or stand for election to the Convention, excluding therefore the young radicals who started the year of protests; members of trade unions and social movements will be barred from standing for election to the CC unless they abandon their positions in these organisations. Any changes made to the Constitution then have to be agreed by two-thirds of the CC, giving the right-wing a veto power if they make up one third (52 of 155) of the delegates. The new Constitution would then be signed by Piñera, violator of human rights.

The radical left movements that make up the Command include the Revolutionary Workers Party, Socialist Movement of Workers, Collective Anticapitalist Movement, and extends to dozens of other groups including women’s movements, LGBTQ movements, indigenous people’s movements, labour syndicates and local organisations. Leading up to the one-year anniversary of the estallido social (‘social explosion’), the Command called for renewed protests on the streets demanding a third option: a Constituent Assembly that wais truly free and sovereign from Piñera and the established electoral parties like the opportunist Frente Amplio coalition and Chilean Communist Party, both guilty of voting in favour of criminalising protest and in favour of cutting workers’ wages in order to save employers’ gains during the pandemic.

As the results were broadcast and it became clear that a new Constitution was imminent, hundreds of thousands flooded the streets to celebrate and fireworks were set off in the renamed Plaza Dignidad (formerly Plaza Italia). Despite its limitations, the plebiscite is the most humiliating defeat for Chile’s right wing since the removal of Pinochet in 1988. This victory must be built on for the 36 dead, hundreds blinded by police rubber bullets, thousands others injured and over 2,500 political prisoners, who will not be forgotten by the most organised and revolutionary sections of the Chilean population who take on the task of pushing the movement further.

¡Fuera Piñera!

Free all political prisoners!

For a truly free and sovereign Constituent Assembly!

Sheila Rubio