Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no.8 January/February 1981

The interview below was given to us by Thozamile Botha whilst on a speaking tour in Britain, organised by the Anti Apartheid Movement and the South African Congress of Trade Unions.

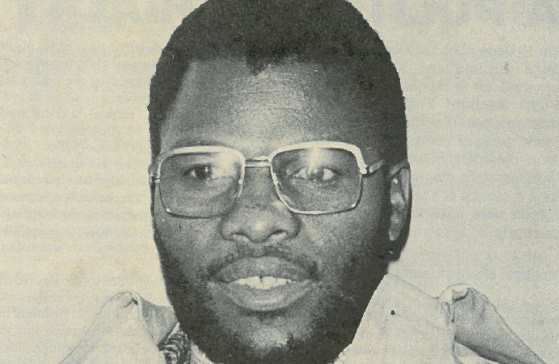

Thozamile Botha is a black South African working class leader who played a leading role in the famous strike at Fords in Port Elizabeth. The history of this strike is recorded in the interview, and particular emphasis placed on the unity between the striking Ford workers and the Port Elizabeth Black Civic Organisation. From the interview we obtain a very clear and stirring picture of the unity that exists between all aspects of the revolutionary struggle in South Africa. It is noteworthy that the racist apartheid regime is now attempting to break up this unity. It is preparing legislation which makes it illegal for any black trade union to have links or association with black community organisations. What fools to believe that this unity can be broken by a piece of legislation. Throughout the whole of last year the black masses of South Africa faced the apartheid regime’s mass murder, torture and imprisonment. Their unity did not break. When there is a mass revolutionary movement led by the ANC no legislation, however many are the guns which back it up, can break the spirit of the black working class. This legislation reveals only the fears of the apartheid regime.

Besides giving a very clear picture of the revolutionary working class movement in South Africa, Thozamile Botha shows very forcefully why the working class in South Africa and in Britain have a common interest in fighting for the complete isolation of the South African regime. His comments on the struggles of the workers at British Leyland and his plea for a united struggle is a true reflection of international working class solidarity.

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! is proud to publish this interview and calls upon all communists and revolutionaries to exert every possible effort to ensure that a mass revolutionary movement is built in this country which is powerful enough to break all British links with the racist apartheid regime in South Africa.

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism!: Last year in South Africa we saw workers’ strikes involving up to 50,000 people at any particular time: we saw the school students strikes; we saw the battles in Cape Town in June 1980; we saw the Free Mandela Campaign; the rent strike in Soweto and the intensification of the ANC’s military campaign highlighted by the attack at Sasolburg. This unification of the economic, social, political and military struggle seems to be a new development in South Africa. Would you like to comment on this.

Thozamile Botha: Yes, well the struggle of the black people is intensifying inside the country. The political consciousness of the people is rising and now they are up in arms against the employer, the capitalist who is exploiting the working class. The workers see their role as part and parcel of the total liberation struggle. They see the need to liberate themselves as a class against exploitation. But one thing that is important is that they cannot be, or they cannot be seen as a class of workers whilst they are under a racist system. That is why today workers are closely aligned with the vanguard of the struggle for South Africa, the ANC and with SACTU, the workers’ union. The workers today are no longer making only economic demands, they are also making political demands. Demands like the total scrapping of job reservation within the plant and equal payment for equal work; integration of training facilities; technical schools, and so forth. These are long-term demands made by the workers today. They are not only fighting for the improvement of their wages. There is now a coordination between the student organisations, the civic organisations and the workers’ organisations because all these forces are fighting for one common goal: the total liberation of the oppressed masses.

FRFI: The Ford strike of October 1979 to January 1980 seemed to be a milestone in the current wave of struggle. It was not only a strike over the dismissal of yourself but soon involved the whole community in struggle. Could you tell us something about the dispute and your role in it?

TB: The Fords Strike has a great significance. I think it was one good example of a strike which involved the community. The Ford strikers did not see themselves as separate from the community. Their problems emanate from work. They have problems of rent increases or bus-fare increases, they could not afford to take their children to school, they could not afford to buy groceries and clothing for themselves because they are underpaid at work. And these problems reflect into the community where they live, where the rate of crime increases because people do not have money while they are working. So that is why Port Elizabeth Black Civic Organisation (Pebco) fully backed the whole strike even in trying to raise funds to assist the workers, while the trade union, the United Auto Workers Union, was refusing to assist the workers on strike, saying that the strike was political. Pebco felt that it was necessary that workers associate themselves fully with the civil organisations because from time to time when workers go on strike if they are in close relation with the civil organisations – they can even appeal to the civic organisations to organise a boycott of certain products of plants who have laid workers off, to pressurise managements to re-employ. So this unity between workers and community is very very necessary. And of course this strike was a good example throughout the country to places like Cape Town where, when the meat workers went on strike, they appealed to the community to boycott that meat. And it was done successfully even by the businessmen. They stopped selling that meat.

FRFI: What were you actually sacked for at the time of the Ford Strike. Why did they dismiss you?

TB: I was dismissed because of my involvement with Pebco. I mean I was in the vanguard of Pebco and the Ford management became dissatisfied with my involvement with Pebco and gave me an ultimatum to choose between Pebco and Ford. I decided to choose Pebco.

FRFI: And then they dismissed you?

TB: Correct.

FRFI: And what happened?

TB: The following day after I had left more than 700 workers walked out and demanded that I should be brought back to the plant to address them on the reasons for my dismissal. The management refused to meet these demands and the workers remained outside. In the morning of this particular day when they made this demand, they distributed leaflets giving the management an ultimatum that on that day I should either be there at 12 noon or else they would walk out. By 12 the management had not met their demands and the workers walked out. They remained outside until the management called me into the plant two days later. We held a meeting to discuss this with the management. They agreed that I should address the workers a day later. I then addressed the workers and the management agreed to reinstate the workers and myself unconditionally with pay for three days.

FRFI: What happened after that?

TB: After that we continued to work for one week but then the white workers within the plant walked out – in fact they did not walk out – they held a meeting outside in the evening and demanded to be paid double for the three days that we were paid and went on further to make statements that their lives were in danger among anti-government elements. They demanded the separation of training and eating facilities. And they also made inflammatory statements that blacks were smelly and that blacks could not behave themselves in the cafeteria. Because I was reinstated they also demanded a reinstatement of a white foreman who was made redundant a month earlier. Immediately that was done the black workers boycotted the cafeteria and demanded that the whites should retract the statement. The management dissociated itself from this and that led to another walk-out by black workers.

The workers now refused to work overtime; they refused to work any unpaid short-time. Though these companies claim that they are paying workers say, in Ford R1.35 an hour, it is R1.40 now — and they regard themselves as a well-paying company — in reality this is far lower than those that are getting even lower rates. This is because these are workers who work only three or four hours a day for about three or four months a year. This means when they work this short time they only get two or three days’ pay a week in spite of the rate increase. The workers also drew up a list of grievances: total stopping of job reservation, promotion of blacks to senior positions and also integration of the training of blacks and whites within the plant. Those were the demands that were made and the workers gave the management 14 days ultimatum after which, when the management refused to meet the demands, they walked out.

FRFI: And how long did that last?

TB: That lasted about two and a half months until Pebco resolved that if Ford was not reinstating the workers they would organise a national boycott of Ford plants, a boycott of liquor outlets that are owned by the government and there would be a day of solidarity when all workers in the Eastern Cape of South Africa would not go to work for one day. There was going to be a peaceful demonstration — in fact this was going to be against the removal of the Walmer Township — and also the students announced in that meeting that they had taken a resolution not to go to school for a week in solidarity with the Ford workers. A day later Ford agreed to reinstate all the workers unconditionally.

FRFI: So in effect that kind of solidarity was, in embryo, what was going to happen throughout the whole country over the next period.

TB: Correct.

FRFI: What happened to you? When were you arrested?

TB: I was kept in detention for 48 days. I was kept at the Sanlam Building the Police Security Offices in Port Elizabeth for 5 days without sleep — 5 days and nights without sleeping — being interrogated right through. And the security police were working shifts on me. I was kept after that about 90 kilometres away from Port Elizabeth. Then, during that time nothing happened until I was released and on release I was banned. Banning means naturally that I could not work in any factory; I could not go to school; I could not be involved in politics; I could not leave home on public holidays and weekends. I had to remain indoors from 6pm to 6am, I could not be visited by friends in the house and I could not meet with more than one person at a time in the street.

FRFI: So you couldn’t earn your livelihood at all.

TB: No. So I had to leave the country.

FRFI: You mentioned the United Auto Workers Union — their refusal to support the strike because it was political. Could you tell us something about that union?

TB: Well, UAW is one of the unions in Ford and the leadership of the UAW did not like Pebco’s involvement in the strike. But of course the strike was in fact about Pebco from the beginning because I was expelled from Fords for my role in Pebco. So they said that the strike was political because Pebco was involved. That is why they refused to even negotiate on behalf of the workers. And then the only time when they eventually did agree to go and negotiate on our behalf they came back to persuade us to be re-employed when we were refusing to be re-employed. By the time we left the plant Ford made it clear that we had lost our jobs. The strike spread to other companies. When we went out at Ford, General Tyre Workers (about 1200 workers) walked out. At SA Adamas papermill about 600 workers walked out. At Ford Engine Plant about 500 workers walked out the same day. And 25 workers walked out at Red Lion Hotel on the same day that we walked out. All these pledged solidarity with the Ford workers while having their own basic demands.

FRFI: Could you give British workers some idea of what it actually means for Black workers in South Africa to go out on strike because British workers might not fully appreciate the significance of this solidarity action.

TB: Yes. Well to start with in South Africa there is a large rate of unemployment so the employers know that when workers go on strike they won’t last for more than two days — that’s what they maintain because they will starve. They know there are blacks in the townships who are unemployed and when they call upon them, they will come. For instance immediately we left the plant, Ford recruited workers outside but not a single person from the black community went to seek work from Fords.

In other words, to go on strike, means sacrifice and to sacrifice to go on strike means you remain outside even if you and your family are starving. For instance in Johannesburg in the Municipality strike more than 2000 workers were sent to the Bantustans because they were migrant labourers. And some of these Bantustan puppet leaders made statements that they have a pool of labour so if the workers on the mines or in the municipality are giving problems they should send them back to the Bantustans and they will give them more workers. So unity of the workers is necessary nationally and also internationally, because those workers who remined on strike for a couple of months were really starving. For instance, by the time that we went back to Ford there were about 100 to 250 workers who had already gone back to work in January because they were starving and there was nothing for them in terms of finance. And nobody was prepared to help at that stage.

When we talk about solidarity, we appeal also to trade unions in Britain and throughout the world, that when we in South Africa go on strike we need their assistance. Not only financially — and we need their financial assistance — but also to put pressure on transnational mother companies outside South Africa so that if these corporations do not reinstate workers in South Africa they will go on strike in their own country in support of the workers in South Africa. Workers should stop production, for example in Britain because they know that if production stops in South Africa, production continues somewhere because these transnational corporations are organised in a very sophisticated way. For instance Leyland in Britain now has threatened that if workers go on strike they will close down. This they can do because they know very well that they have a subsidiary in South Africa and can open it full-scale. So if business goes badly in Britain or the workers are giving problems they will go and open business in South Africa in the cheap labour system. Now if South African workers are going to take their jobs then it means they are working to the disadvantage of the workers in Britain and that is why this co-ordination is very very necessary.

FRFI: In the face of the massive struggles on all levels; economic, social and political, the ruling class in South Africa has begun to argue — and I quote Mr Dennis Etheredge, who is the chairman of the Vaal Reefs Exploration and Mining Company — ‘Blacks must be involved in the private enterprise system or they will choose socialism’. What efforts are the ruling class in South Africa making to try and draw black workers into the private enterprise system, and what success are they having, if any at all?

TB: There are a lot of attempts being made. You see, when you talk about these transnational corporations we are really talking about nothing else but the government. These transnational corporations are the government. The government’s foreign policy is determined by these foreign companies. So when they want to implement something the government has no option but to implement it. For instance Anglo American, whilst owning the mines, are also directly involved in the building of arms and they have shares in Armscor. Now in 1976 they introduced what is called the Urban Foundation. The aim of this body was to build first, middleclass houses, to build community halls and sporting grounds. Now they said in their policy that they are improving the quality of life of the urban blacks. But to them to improve the quality of life means to build community halls, to build schools. In the past they used to build schools from ash bricks; today they build schools from red brick and they have floors and ceilings now; they are adequately electrified. In the past there was no electricity in schools; there were no floors — they had cement floors and no ceilings. Instead of changing the Bantu Education system which we want to be changed — this inferior racist education — they are changing the face of the classrooms in the hope that the students will feel that there is change instead of boycotting the schools.

They are opening opportunities now for blacks to participate, to be bank managers, to manage even white shops in town. These blacks are now with the system, they have to protect the white business. Meanwhile, this is not benefiting the blacks. In fact some people are confused in saying that now opportunities are open to blacks. Far from opening opportunities to blacks, this is benefiting the employer, because instead of paying the blacks the salary that would be paid to a white man doing a similar job, they pay him a quarter of that. If a white man was going to get R1000 a month in a job, a black man would get R250 or R300. In fact this is not an improvement at all. It is exploitation at a very high degree. So the sucking of some of the blacks into the system — part of P W Botha’s Total Strategy — is aimed at winning a certain section of our people to the side of the system so as to protect the system. They say that there are changes whereas in fact they are only cosmetic changes and reforms.

FRFI: So what success is it having? Or can it have success?

TB: Certainly it has not had success. For instance when he introduced the Community Councils he thought that people would accept this and people rejected this thing in total. Now he introduced the President’s Council: nobody wanted to take part in that because it is nothing else than a stooge vote where some blacks are hoping to participate in an advisory capacity. And where there are things that are non-negotiable. For instance the scrapping of the racist laws are not negotiable. They won’t be changed. They will remain intact. They can discuss any other things: the building of houses of the blacks where they live. There is no talk about integration of blacks or people who live in South Africa.

FRFI: So what you are saying is that the racist system in South Africa depends on the poverty and the oppression of blacks — the black working class, and there is no fundamental way out of that as long as this racist system exists.

TB: As long as the racist system exists: as long as the people do not have a share in the wealth of the land: as long as the people do not have a share in the land itself our problems will exist. For instance today, blacks who number between 21-23 million are concentrated on 13% of the barren pieces of land that are scattered all over the country, along the borders of the neighbouring states, whilst 4-5 million whites enjoy 87 per cent of the total land — highly industrialised areas — all the big cities. All the industrial areas and all the farmland , the rich farms — this is owned by whites. No black has the right even to buy a plot in the urban areas to build a house. If one buys, he buys the walls, not the plot. The plot belongs to the government, but all other groups can buy. So this is a very good example that they don’t want change in South Africa. Even these corporations who are talking about a change, for instance Ford, has built a training institution for blacks only and a training institution for whites. For blacks to go and train in a white institution, they have got to go and obtain a permit, a special permit. This means there can be no training of blacks to senior technicians while the system remains.

FRFI: We have talked a lot about the economic and political struggles of the black working class so far. The attack on Sasol by the ANC had a massive impact worldwide. Could you say something about the ANC’s role in South Africa and how the military campaign fits in with the other campaigns that we have talked about so far. How significant is the military campaign? How necessary is the military campaign?

TB: Certainly the military campaign is very very necessary. The ANC is waging attacks on key government installations like the Sasol attack. Because if one attacks these key government installations like oil, this cripples the economy of the country. In Sasol they lost about R6m — which was a set-back for the economy of the country. The ANC’s military attack is aimed at crippling the economy of the country and also aims to mobilise the masses of our people for there is no way we can talk about peaceful change in South Africa these days. There can be no peaceful change when the government is killing people today who are protesting against and rejecting the government-imposed bodies.

FRFI: To what extent is there support for the ANC in South Africa?

TB: Well the demands that are made by the workers today — equal pay for equal work and the scrapping of job reservation, the treatment of all workers on an equal basis — those are incorporated in the Freedom Charter. Housing and security, the sharing of the land and the redistribution of the wealth of the country. These are the demands that are made by the people of the country today and all these demands are incorporated in the Freedom Charter. This means, therefore, that people are fighting for demands which are being made by the ANC. This shows the support for the ANC.

FRFI: In a recent dispute — the Collondale Cannery dispute — where 400 workers came out on strike in support of 5 dismissed black workers, the Free Mandela Campaign supported the strike and was in return given support by the strikers. Is this the kind of development that is taking place between the political and economic struggle and the association with the ANC and its leaders?

TB: Certainly the workers, as I have indicated, see themselves as part and parcel of the true liberation struggle. The demands that they are fighting for are the demands that Mandela is fighting for. The Free Mandela Campaign is a campaign for the freeing of a leader of the liberation struggle of the people of South Africa; a leader of the workers, a leader of the total people of South Africa. That is why you see a close relationship between the Free Mandela Campaign and the struggle of the workers.

FRFI: The ANC has called for the total isolation of South Africa: economic, political, cultural — in every way whatsoever. What have you to say to British workers, like steel workers, for example, tens of thousands of whom are unemployed with some of them accepting jobs in South Africa because ISCOR has come to this country to recruit them. What would you say to these workers?

TB: This is very dangerous. I remember that a number of British workers were recruited by the South African Government to go and work in South Africa. Today South Africa is still short of skilled workers. Yet blacks are denied the opportunity to train. Today there is not a single black technician in South Africa. They cannot be trained as technicians. Yet they know that the South African Government will go outside and recruit workers from other countries to take those positions. We are making a sincere appeal to the workers of the world not to go to South Africa to take jobs that would have been given to blacks.

We are calling for the total isolation of South Africa in every respect. The whole economy in South Africa relies and depends to a very large extent on foreign expertise. Today, for instance, in computer production, 40% of components have come from the United States of America and a large number of people who are working in these computer industries come particularly from Britain and the US. Today South Africa depends to a very large extent on the more than 2,000 transnational corporations that have invested in South Africa. About 1,200 British corporations and about 400 US corporations, then West Germany, France and Canada. So we are calling for the complete isolation of South Africa and appealing to workers to refrain from going to South Africa to take jobs which otherwise blacks would have to be trained for.

FRFI: You are also asking the British workers to stop cultural links with South Africa. Why is this important?

TB: For instance, let us take sport. Recently the British Lions went to play rugby there despite a protest by the South African blacks that they must not go. They were totally boycotted in South Africa because sport and cultural activities in South Africa play a very major role in politics. They say there are changes in South Africa. The government say they are changing, that blacks can play with whites when really blacks can only play at international level. No blacks can play at team level. At school, no white school can play with a black school. No black team can play with a white team at local level. They can only play at international level. And that is no change. It is just a window-dressing to confuse the outside world that there are changes in South Africa. So they are playing a very major role in the reforms that are brought about by the South African ruling party. They are playing into the hands of the South African regime when they go there to play games or sport when in fact the blacks in South Africa are denied these opportunities.

FRFI: And you are also saying it is in the interests of British workers to totally isolate South Africa because, as you said earlier, South Africa is being used as, if you like, a second front, against the workers in Britain.

TB: Certainly. For instance, the threat that is made by Leyland is a threat to British workers that they should not make their demands. If they make their demands, we will close down. That is what they are saying. They will close down and they know that they have got a straight run. They will go and extend business in South Africa. So British workers must try by all means to stop companies closing down in Britain and going to South Africa to open business. All this they can do by campaigning for sanctions against South Africa. British workers must understand that in the motor industry there is not a single car that is produced in South Africa today that has no foreign parts. And these parts are built here in Britain, in the US, in Germany, in France and Israel. Workers have got to put pressure on their governments to stop any links with South Africa. And the workers have got that power — to impose sanctions on South Africa, to stop bank loans to South Africa and to withdraw their funds that are invested in banks and in links with South Africa. These are some of the methods that can be applied.

—————————————

ANC FREEDOM FIGHTERS SENTENCED TO DEATH

On 26 November 1980, three members of the ANC, Ncimbithi Lubisi, Petrus Mashigo and Naphtali Manana, were sentenced to death by the racist Supreme Court in Pretoria, South Africa. They have been condemned to die for their part in the attack on a bastion of the murderous apartheid regime —the Soekmekaar police station, in January 1980.

Along with six other ANC comrades, they were charged with high treason, murder, robbery and taking part in ‘terrorist’ (ie armed struggle) activities and tried in what has become known as the Silverton Siege Trial. In January 1980 attacks took place not only against the police station but also against the Silverton branch of the Volkskas bank. These blows struck against institutions which hoard the wealth robbed from black workers and against the force that protects this plunder led to the nine being found guilty of high treason (ie the freedom struggle against the racist apartheid regime).

Three of these freedom fighters now languish in jail awaiting death. The African National Congress has launched a campaign to save the lives of these comrades. They are asking that protests be sent immediately to the racist regime and are asking all supporters of the freedom war in South Africa to demand that captured guerrilla fighters be treated as prisoners of war. FRFI fully supports this campaign and calls on readers and supporters to send protests to

The South African Embassy, Trafalgar Square and PW Botha, Pretoria, South Africa