Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no. 79, July 1988

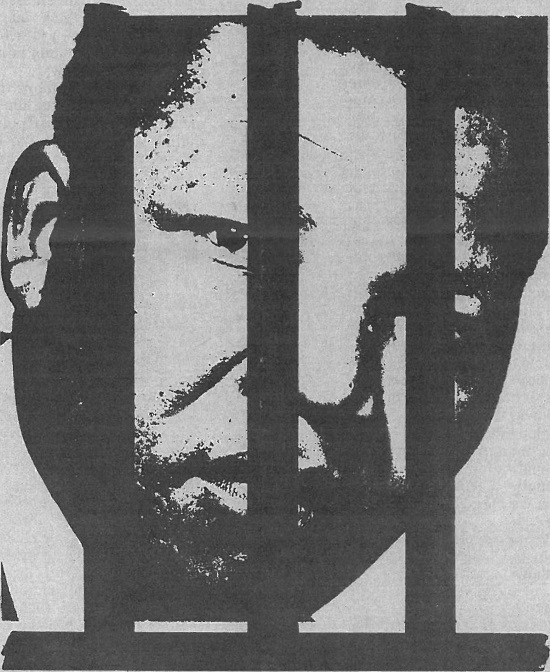

For forty years Nelson Mandela has been in the forefront of the liberation struggle in South Africa. His political leadership spans the years of the defiance campaigns, the turn to the armed struggle and then, the last twenty-six years of resistance as a political prisoner. FRFI pays tribute to Nelson Mandela on his 70th birthday.

Nelson Mandela was born in the rural Transkei on 18 July 1918. As a young man he attended Fort Hare University, from which he was expelled after 2 years for engaging in student pro-tests. After short spells as a mine security guard and working in an estate agent’s office, Mandela took articles in a firm of attorneys – he was studying to be a lawyer. Along with Oliver Tambo and Walter Sisulu, his friends from the Transkei, Mandela joined the Youth League of the African National Congress in 1944. In 1948 the whites elected a vicious right-wing government dedicated to entrenching white supremacy and racial segregation – apartheid.

The Youth League’s militant proposals for resistance were incorporated into the Programme of Action, adopted by the ANC in 1949. The ANC committed itself to fighting for political rights, especially one adult-one vote, and decided:

‘to undertake a campaign to educate our people on this issue and, in addition, to employ the following weapons: immediate and active boycott, strike, civil disobedience, non-cooperation and such other means as may bring about the accomplishment and realisation of our aspirations.’

The plans to implement a civil disobedience strategy were laid out by Walter Sisulu, who with Mandela and Tambo had been elected onto the leadership of the ANC. The new ANC led a stay-away strike on 26 June 1950 and in 1952 launched the Campaign for the Defiance of Unjust Laws. Mandela was the Volunteer-in-Chief.

His qualities as an inspirational leader, combining dignity with a fiery determination to end all racism, encouraged 8,500 volunteers working in disciplined, non-violent groups to deliberately break apartheid laws.

The ANC’s membership shot up from 7,000 to 100,000 in one year. In some areas of the Eastern Cape, rioting broke out. Mandela and a hundred other ANC, Indian and trade union leaders were banned.

By 1953 the divisions were made crystal clear by Mandela:

‘In South Africa, where the entire population is almost split into two hostile camps in consequence of the policy of racial discrimination, and where recent political events have made the struggle between oppressor and oppressed more acute, there can be no middle course. The fault of the Liberals – and this spells their doom – is to attempt to strike just such a course. They believe in criticising and condemning the government for its reactionary policies, but they are afraid to identify themselves with the people and the task of mobilising that social force capable of lifting the struggle to higher levels’.

Mandela argued that the repression had made it impossible to wage the struggle mainly through the old methods of public meetings and printed circulars. The ANC must adopt new methods:

‘If you are not allowed to have your meetings publicly, then you must hold them over your machines in the factories, on the trains and buses as you travel home. You must have them in your villages and shanty towns. You must make every home, every shack and every mud structure where our people live, a branch of the trade union movement and you must never surrender.’

The ANC entered alliance with other groups which brought together a congress of over 3,000 people (the police kept many thousands away) in Kliptown in 1955 to adopt the Freedom Charter. The Freedom Charter became the guiding document of the Congress Alliance, and is to this day widely debated in the trade unions and liberation movements.

The police conducted mass raids on 5 December 1956. Mandela and 155 other political leaders were charged with High Treason, for conspiring to overthrow the state by violent means. The trial lasted until 1961 when the last accused was finally acquitted.

Towards the end of the 1950s mass protests against the pass laws escalated. The PAC organised the Sharpeville and Langa demonstrations which were put down with the utmost brutality. It was the end of the era of civil disobedience. Mandela wrote:

‘In March 1960 after the murderous killing of about seventy Africans in Sharpeville a state of emergency was declared and close on 20,000 people were detained without trial . . . ‘

In April 1960 the Government went further and completely outlawed both the African National Congress and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania. By resorting to these drastic methods, the Government had hoped to silence all opposition to its harsh policies and to remove all threats to the privileged position of whites in the country. It had hoped for days of perfect peace and comfort for white South Africa, free from revolt and revolution. But the days of revolt were at hand.

Mandela went underground to organise a 3 day stayaway. It was a limited success.

The people demanded that the fire of repression be met with the fire of resistance. Mandela reported:

‘Of all the observations made on the strike, none has brought forth so much heat and emotion as the stress and emphasis we put on non-violence. Our most loyal supporters, whose courage and devotion has never been doubted, unanimously and strenuously disagreed with this approach.’

The black majority in South Africa had by now exhausted every channel of peaceful protest, and had been met by bloody murder. In this their experience was no different to colonised and oppressed peoples throughout Africa and the world over. The people started arming themselves. In rural areas and the townships uprisings erupted. The PAC formed POQO and the ANC formed Umkhonto we Sizwe, with Mandela as Commander-in-Chief, to conduct sabotage operations against economic targets. The armed struggle was a reality, the only question was now its degree of organisation and direction to meet political objectives.

Early in 1962 Mandela left South Africa and visited various African states and Britain before returning to the underground. He was captured in August 1962 and sentenced to 3 years imprisonment for incitement to strike and 2 years for leaving the country without valid travel documents.

Then in July 1963 the security police raided a farmstead at Rivonia, near Johannesburg, and captured many of the ANC leaders. Mandela was the first accused in the Rivonia Treason Trial – he along with Sisulu and six others were sentenced to life imprisonment with no prospect of remission.

The black political prisoners were sent to Robben Island. In prison, as he had been outside, Mandela became a symbol of resistance to white racist rule. Hundreds of ANC and PAC freedom fighters were imprisoned.

Robert Sobukwe, the leader of the PAC, was kept in isolation from the rest of tree political prisoners. The politicals were in turn separated from those convicted of ‘criminal’ offences. The back-breaking prison labour was crushing rocks in the yard, then digging in the lime quarry and collecting seaweed. These rigours, the sadistic and cruel bullying of the warders required a constant struggle for basic improvements.

These were hard years. Many released prisoners acknowledge that it was their political convictions and the fortitude of their leaders which kept them going. The prisoners gleaned what news they could from new arrivals – the Namibian freedom fighters and the generation of Soweto 1976, and from the infrequent prison visits. Mandela’s connection with the ANC and the mass movement, particularly through his wife Winnie, has never been broken.

South Africa’s Minister of Justice, Jimmy Kruger, offered Mandela his release in 1973 if he recognised the independence of the Transkei bantustan and agreed to settle there. The price of release would have been a propaganda victory for apartheid’s policy of ‘separate development’. Mandela refused the condition.

The regime tried another tactic. In 1982 Mandela and Sisulu together with fellow Rivonia trialists Ahmed Kathrada, Raymond Mhlaba and Andrew Mlangeni were moved to Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison in Capetown. They were joined by Patrick Maquebela. The six were put in a common dormitory cell, With the move came moderate improvement in material conditions – the right to receive newspapers, body contact on family visits – but it has meant complete isolation from all other prisoners. The six exercise on their own in a small L-shaped yard – their only view is of a patch of sky.

Under tremendous domestic and international pressure PW Botha offered Mandela (along with other leading ANC and PAC prisoners) his release in January 1985 – with a condition:

‘All that is required of him now is that he should unconditionally reject violence as a political instrument.’

Most of the prisoners refused to accept the condition. Mandela’s reply was forthright. His daughter Zinzi read it out to a mass gathering in Soweto. It is the measure of his leadership than when offered his freedom, he recognised that there would be no freedom if he separated himself from the mass struggle for liberation:

‘I cherish my own freedom dearly but care even more for your freedom. Too many have died since I went to prison . . . I cannot sell my birthright nor am I prepared to sell the birthright of the people to be free. ‘I am in prison as the representative of the people and of your organisation, the African National Congress, which is banned. What freedom am I being offered while the organisation of the people remains banned? ‘I cannot and will not give any undertaking at a time when I and you, the people, are not free. Your freedom and mine cannot be separated. I will return’.

APARTHEID TYRANNY

Thanks for your continued support of progressive forces within South Africa. While we try and work towards freedom, non-racialism and democracy we are continually harassed and our leaders are detained. Every time something happens in South Africa (like the recent bannings) we think ‘How much further can this state go?’ – each time they find a new way to oppress all South Africans.

What I am saying to you is that you must not let the horrific monotony of apartheid tyranny lead to your not exposing it on a steady basis. I like to think that this would never happen but sometimes circumstances are just overwhelming. How in contact are you with student movements in South Africa? I hope it’s quite a large extent – we are the future!

Sorry but I must withhold my name and address.

GT, SOUTH AFRICA