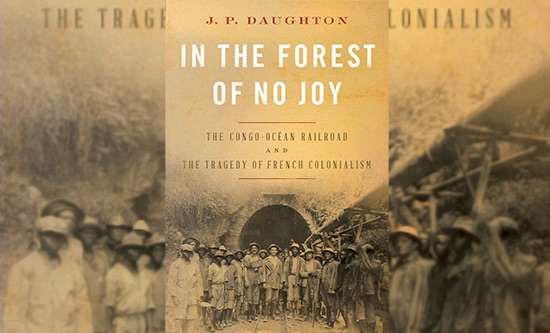

■ In the forest of no joy: the Congo-Océan Railroad and the tragedy of French colonialism, JP Daughton, Norton 2021, £23.99, 384pp

The cartoon in Le Journal du Peuple of 28 April 1929 says it all. The archetypal cigar-smoking French capitalist is boasting of how cheap the Congo-Océan project is, and that it ‘only costs us 2,000 “negroes” per kilometre’. Behind him the Congo-Océan railway line runs over the dead bodies of Africans. Welcome to the cruel world of the Congo-Océan, the railway built from Brazzaville, the capital of what was then French equatorial Africa, to Pointe-Noire, from 1921-34. A world where black lives do not matter. Tens of thousands were snuffed out in the construction of Congo-Océan. Even official figures admit to anything from 16,000 to 23,000 deaths; these are notorious underestimations, the real figure is likely to be between 30,000 and 60,000.

This relatively little-known but appallingly brutal construction project is the subject matter of In the forest of no joy by JP Daughton. In relentless, harrowing detail Daughton exposes the cruel reality behind the sanctimonious bilge of the French colonial rulers. A project that was designed to facilitate the transport of raw materials from the colony to the metropolis was passed off as being for the benefit of the African population. Here is a little glimpse of the reality – one of many passages I could have chosen: ‘It was easy to lose sight of the human experience of boat travel (from villages to the construction site), crowded with standing men and women. Boats are sullied with the stench and filth of urine, faeces and vomit. The lack of toilets on a boat carrying anywhere from two hundred to six hundred passengers meant that men and women, pushed together to the point of immorality, have little choice but to soil their own space’ (p112).

To the effects of disease, starvation must be added. As Daughton puts it, ‘the food ration of rice and dried fish provides less food than concentration camp inmates received in Nazi-occupied Europe’ (p113). No wonder that some recruits opted to end it all by jumping in the river, to drown or be eaten by crocodiles.

In contrast to the squalor that awaited the recruits of Congo-Océan, Daughton provides a glimpse of the luxury enjoyed by their European masters. Orders of suppliers from the Batingholles (the construction firm) included ‘two thousand litres of red wine, two thousand of white, and two cases of sparkling wine, – a case each of veal, pork covered in fat, sausages, salmon and sardines, kilos of green beans, brussels sprouts and carrots, two cases of jam, coffee and sugar’ (p200).

Obscene material privilege was accompanied by power of life and death over the African workforce: ‘from punching and raping, to burning villages and torture and murdering, white abuse of Africans was a regular part of life in equatorial Africa’ (p153). Time after time African complaints were dismissed by the authorities for want of evidence, for which the bar was set impossibly high. A couple of the very few cases that made it to court are quoted by Daughton: a supervisor who beat a worker with a machete, causing him wounds that left him unable to work for 37 days, was fined 150 francs. Another, who murdered a worker got six months in jail (p160).

And so it goes on, chapter after meticulous chapter, all vividly illustrating Mahatma Gandhi’s words when he asked what he thought of Western civilisation: ‘I think it would be a wonderful idea.’ It would have been amazing if there had not been widespread resistance. As Daughton puts it, ‘when vandalism failed to make its point, men refused to work, walked off the job, reported poor treatment en masse to the labour service, or simply left and never returned… disobeying orders risked abuse, punishment, withheld salaries… and for those who chose to abandon the construction work entirely, the danger was death’ (p174).

But this was a lot more useful than relying on official channels. Time and again this would mean the authorities investigating themselves under the watchful eye of governor-general Raphael Antonetti, and absolving themselves of all responsibility, although African subordinates could always be blamed. Investigations by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) were no more use – the ILO simply asked what regulations governed African labour, and Antonetti responded with a list of them which bore so little relation to reality that they belonged in a joke book. The ILO chose to swallow it whole. The French delegate, one Leon Jouhaux, notoriously a representative of the right-opportunist trend of French ‘socialism’, put the matter in terms that could have been (maybe were) taken from Antonetti: ‘the necessities of civilisation require the use of forced labour to raise the native peoples out of their present life’ (p253).

But there was a more principled opposition to the crimes of French colonialism: ‘communists were among the very few in the national assembly who actively attacked colonial policies, and they were commonly dismissed out of hand for wanting, as one colonial minister put it, to see colonial populations rise up against France’ (p249).

It is doubtful whether any review of this length could do full justice to Daughton’s work and yet, somehow, I finished reading it still wanting more. How so? Because the crimes of imperialism, which pillaged the African continent by military force in the period covered by the book, and continued to do so even to this day, largely through international financial institutions, are such that revolutionary political organisation is needed to overcome them. For Daughton, who ‘has provided useful commentary for the Atlantic, Newsweek, Times and CNN’, as the inside cover informs us, I suspect that would be a step too far…

Mike Webber

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No 288, June/July 2022