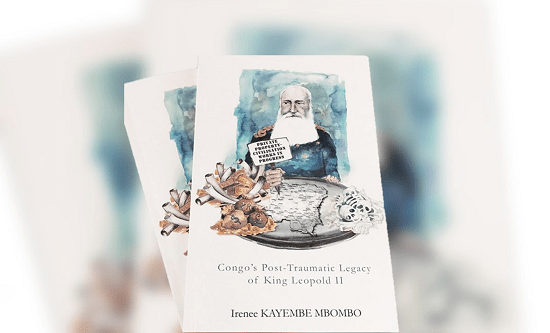

Congo’s Post-Traumatic Legacy of King Leopold II by Irenee Mbombo Kayembe

Paperback, £11.99 2017

If you do not know anything about the history of Belgian imperialism in Africa, this short history of the genocidal occupation of the Congo under the direction of King Leopold, and the traumatic legacy that the country continues to suffer today, is an important and accessible read. The primary intended audience for the work, however, is the Congolese diaspora in Europe: those who carry the trauma of the genocide with them and manifest it in myriad ways.

Written by comrade Irenee Mbombo Kayembe, whom Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! supporters have worked with in anti-imperialist and migrant solidarity campaigns, the book describes how so much of European ‘civilisation’ came about through ‘contact with Africa… the destruction of our homes, the looting of our lands and people, and the theft of our property is what Europeans’ civilisation was about’. It goes on to spell out in graphic terms how colonialism in general, and Belgian colonialism in particular, carried out this looting and destruction by a combination of sheer brutality, religious conversion and a variety of techniques designed to persuade Africans of their own inferiority in order the better to steal from them.

Following the 1885 Berlin Conference, which heralded the most brutal phase of imperialist conquest and division of Africa, the Belgian king and his coterie inflicted sustained pain and humiliation, especially in their quest to bleed the vast rainforest of its rich resources of rubber. Descriptions of these horrors are followed by an analysis of the collective psychological legacy of that brutality which continues to be felt today in what Kayembe describes as ‘post-traumatic King Leopold II syndrome’: ‘a condition that exists because of the multigenerational oppression suffered by the Congolese indigenous and their descendants resulting from the centuries of slavery based on the belief in genetic inferiority and the inequalities that prevail to this day.’

So bleak is the recounting of the rape and plunder of Congo and the description of the continued trauma, it is difficult for the author to conclude on a positive note, but Kayembe tries to do this, by ending with some suggestions for healing the damage: ‘Understand why we are so low’, ‘Telling our story’, ‘Getting the support we need’, ‘Stress Less’, ‘Readjusting goals and establishing Strong Leadership’. Although the author himself is a socialist, who points to Cuba as a role model, the short term suggested goals are pitched at a psychological, rather than political level, presumably on the premise that the damage runs so deep that unless a collective consciousness and self worth are first rebuilt, there is no basis of co-operation or understanding on which to begin to construct a political movement.