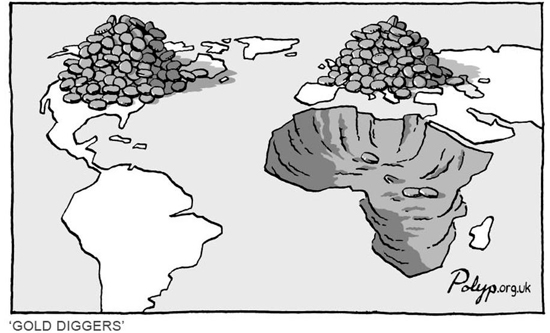

A recent report by War on Want, The New Colonialism: Britain’s scramble for Africa’s energy and mineral resources, underlines the continued role of Britain as one of the world’s dominant imperialist powers.1 Researcher Mark Curtis has once again produced a vital report providing a savage indictment of the capitalist system. The report exposes the naked plunder by British extractive companies of African resources, ripping minerals, oil and gas out of the ground without concern for the human, social, and environmental cost. All this wealth is then transferred out of Africa through the City of London and tax havens. The report provides ammunition for revolutionaries in the fight against imperialism, in solidarity with African resistance to the plunder and destruction of their countries.

The New Colonialism examines the operations of companies listed on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) with mining or energy interests in Africa. 101 LSE-listed companies have such operations in sub-Saharan Africa – covering 37 countries in total. Most of the 101 companies are British: 59 are incorporated in the UK, and 12 others are incorporated in Guernsey and Jersey – British tax havens. Others operate from London despite being incorporated elsewhere, with 25 incorporated in tax havens. These companies play a dominant role in the plunder of major minerals and energy resources from Africa. They control resources worth more than $1 trillion:

- 6.6 billion barrels of oil

- 79.5 million ounces of gold

- 699.3 million carats of diamonds

- 3.6 billion tonnes of coal

- 287 million ounces of platinum,

- huge reserves of gas, copper, silver, cobalt, bauxite and other minerals.

Corporate plunder

The report gives exhaustive detail about these 101 companies and their operations. Some of the most notable include:

- Royal Dutch Shell: this Anglo-Dutch energy giant controls 691 million barrels of oil in Africa, much of this in Nigeria. Shell’s operations in Nigeria are infamous for environmental destruction and the violent suppression of local resistance, including the execution of Ogoni campaigner Ken Saro-Wiwa in 1995.

- Glencore: this giant corporation, incorporated in Jersey, known mainly as a commodity trader, controls 175 million barrels of African oil, and has huge stakes in 25 coal mines in South Africa, containing 901 million tonnes of coal. It holds a significant stake in Zambian copper mining, which is dominated by LSE-listed companies.

- Anglo-American: this giant British mining corporation is dominant in several sectors. Through its subsidiary De Beers it controls 316 million carats of diamonds in Southern Africa. It also controls 659 million tonnes of coal, and 200 million ounces of platinum, both in South Africa. It is the world’s largest producer of platinum group metals.

The continued capital accumulation of these companies relies significantly on the actions of the state in which they are incorporated or operate from.

The role of the British state

Curtis examines the central role played by the British state and its foreign policy – whether under Conservative or Labour governments – in fighting for LSE-listed companies’ access to African resources. He explains how British governments: ‘have long been fierce advocates of liberalised trade and investment regimes in Africa that provide access to markets for foreign companies. They have also consistently opposed African countries putting up regulatory or protectionist barriers to such trade and investment. In addition, Britain has been a major advocate for policies promoting low corporate taxes in Africa’. In order to keep African countries dependent and oppressed, imperialist governments and institutions: ‘have effectively argued that Africa should continue as a primary resource provider, exporting unprocessed raw materials and making other (Northern [ie imperialist]) countries rich from the processing of these materials.’

Curtis does not go as far as explaining that opposition to foreign policy priorities will often result in a military coup or overt imperialist military intervention, with Britain playing a major role. The destruction of Libya in 2011 is just one recent example. Libya contains 60 billion barrels of high-quality oil, as well as large reserves of gas and other resources. Shortly before the NATO onslaught, Libya had granted Russian gas giant Gazprom and Chinese companies access to many of these resources. President Gaddafi had also made strides towards promoting investment in mineral processing in Africa through the Libyan Arab Investment Company, and was beginning attempts to unite the continent in an ‘Arab-African Union’.2 These attempts at independence from the NATO imperialists would not be tolerated.

The report’s title suggests that this ‘New Colonialism’ is a recent phenomenon. However, Curtis draws a clear link between the period before formal decolonisation and today: ‘The current phase of the British scramble for Africa is a continuation of British foreign policy goals since 1945. Then, as now, access to raw materials was a major factor – often the major factor – in British foreign policy in Africa.’ Curtis quotes Labour Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, who in 1948 argued that Britain needed ‘to develop the African continent, and to make its resources available to all’ – Curtis adds ‘(ie Britain).’ This post-war period was a difficult period for British imperialism, and it resolved to solve its financial problems through renewed colonial plunder. The exploitation of Nigeria and the Gold Coast (now Ghana) in West Africa were key to the post-war reconstruction of Britain led by the Labour Party under Clement Attlee: ‘From 1948 in particular, the Empire was to be milked of all the dollars and superprofits it could earn. Resistance to this was to be ruthlessly and murderously put down … Such plunder was to cushion the British working class from the worst effects of the crisis, and help prevent a repetition of the revolutionary struggles that occurred after the First Imperialist War’ (Robert Clough).3

So instead of a ‘New Colonialism’ we see an unbroken British exploitation of Africa’s raw materials. Many of the countries host to the extractive parasites exposed in the report, once belonged to Britain’s formal empire – South Africa, Zambia, Nigeria, Tanzania, Botswana. However, the reach of British imperialism now goes far beyond this. It is important to recognise the role this massive imperialist plunder continues to play in propping up a significant section of the British working class as a privileged ‘labour aristocracy’ – benefiting from, and supporting, this robbery of Africa.

Britain’s ‘development aid’

Britain’s aid policy is used to open up markets and access to resources. Curtis explains how a new vehicle for the plunder of Africa was introduced by the British government in November 2013 – the High Level Prosperity Partnership (HLPP). This initiative involves the Foreign Office and the Department for International Development (DFID) partnering with Britain’s extractive companies to access resources in five African countries – Angola, Ghana, Mozambique, Côte d’Ivoire and Tanzania. Four of the five HLPP countries ‘are developing new oil or gas fields’. In Tanzania – as explained in a press release co-signed by DFID – the HLPP ‘intends to double the number of British companies doing business in the country’.

Curtis demonstrates eight examples of the revolving door between the British government and these extractive companies. Just one example: one of DFID’s non-executive directors, Vivienne Cox, until recently sat on the BG Group board. BG Group (previously British Gas), taken over by Shell in 2016, controls 16 trillion cubic feet of gas in Tanzania. DFID permanent secretary Mark Lowcock’s meeting with BG Group in November 2011, was ‘described in a DFID document as a ‘discussion on extractive opportunities in Tanzania’. The HLPP also includes a partnership ‘between East Africa, leading businesses and the London Stock Exchange Group’! In January 2014, the LSE Group and DFID signed a memorandum of understanding. DFID, as all other government departments, works for British imperialism.

The human cost

This discussion of the convoluted machinery of British imperialism can obscure the massive human cost of the British plunder of Africa. Curtis examines several case studies of the exploitative labour practices required for British companies to continue extracting with high profit margins. He highlights the environmental and social destruction of Rio Tinto’s mining activities in Madagascar, with local families affected by the mining activities, and the ‘conservation area’ set up by Rio Tinto to offset the environmental damage of the mine. Another case study examines the operations of British companies in the occupied Western Sahara. International law recognises the rights of the Saharawi people to self-determination against the Moroccan occupation, backed up by 100 UN resolutions. Morocco denies the Saharawi people the rights of association and expression, and represses dissent. Despite this, six LSE-listed companies have permits for oil exploration there, including a subsidiary of Glencore, and the Edinburgh-based Cairn Energy.

Finally Curtis examines the operations of British copper mining companies in Zambia. Zambia receives insignificant tax revenues from the huge sums made by British mining companies – the Deputy Finance Minister suggested in 2012 that Zambia was losing up to $2bn a year due to tax avoidance, and War on Want estimates that this could be as high as $3bn. As well as criminally low corporation and export taxes, companies operating in Zambia use networks of tax havens which adds to the ease with which they avoid tax on their profits. Despite this, copper mining has a huge human and environmental cost, with ‘rivers of acid’ running through Zambian villages, with contaminated water drunk by 40,000 people causing liver and kidney problems, and miscarriages.

The well-known massacre at the Marikana platinum mine in South Africa in 2012, owned by Lonmin, is just the most shocking of a series of killings for which British mining companies bear considerable responsibility.4 Mass relocations without adequate compensation are also common in mining projects. Beyond these direct abuses of Britain’s extractive companies is the broader social cost of this robbery. In the light of the billions being taken out of Africa by multinational corporations, the devastation caused by curable diseases, a lack of clean water, food and infrastructure, is largely the responsibility of Britain and other imperialist countries. Military coups, civil wars, not to mention imperialism’s overt interventions, are all also inextricably linked to the profits to be made from this extractive plunder.

Anti-imperialist resistance

In the face of its overwhelming indictment of the capitalist system, Curtis’ report can only make ‘recommendations’ to the British government. However, to suggest that such recommendations could have an influence on those in control of British imperialism, or that they will encourage huge companies to give up their phenomenal resource wealth, is naïve at best. In the face of an economic system sinking deeper into crisis, desperate to wring profits out of human labour and natural resources anywhere in the world it can find them, making progress towards African resource sovereignty will take a massive, organised struggle. A movement must be built in this country which recognises that the plunder of Africa is not due to the greed of a few CEOs, and that it cannot be challenged by changing the Foreign Secretary or the Minister for International Development. It can only be challenged by fighting to overthrow the entire economic system, its defenders and apologists.

The resistance of workers and oppressed communities in Africa shows us the way, and any movement here must fight in solidarity with their struggles. The New Colonialism gives examples of mass protests against the operations of British companies, from the workers’ occupation of Inata gold mine in Burkina Faso, to mass trespasses by communities on land from which they had been relocated, and the huge strikes of South African gold miners. In Britain we have a special responsibility to organise against these companies, and against the state which facilitates this extraction and backs it up with bombs and special forces. We have a responsibility to build a mass movement against imperialism.

Toby Harbertson

See also: ‘The Great African Robbery’, Eric Ogbogbo, FRFI 246

www.revolutionarycommunist.org/africa/africa/4087-tg200815

1. The New Colonialism: Britain’s scramble for Africa’s energy and mineral resources, Mark Curtis and War on Want. Available to download free at: www.waronwant.org/resources/new-colonialism-britains-scramble-africas-energy-and-mineral-resources

2. Sowing Chaos: Libya in the wake of humanitarian intervention, Paolo Sensini, Clarity Press, 2016

3. Labour: a Party fit for imperialism (2nd edition), Robert Clough, Larkin Publications, 2014

4. ‘Questions raised about the role of British company in South African mining massacre’, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, 24 November 2013, www.thebureauinvestigates.com/2013/11/24/questions-raised-about-role-of-british-company-in-south-african-mining-massacre/

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 252 August/September 2016