Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No 113, June/July 1993

In 1979 the RCG produced issue 9 of the journal Revolutionary Communist, containing the article ‘Racism, Imperialism and the Working Class’. This was a study of the living conditions of black people in Britain and an analysis of the way that imperialism’s incessant drive for profit abroad has created a growing oppressed layer of the working class at home which has no stake in the capitalist system.

The 14 years since Revolutionary Communist 9 was written have been years of continuous Tory government in which the mini-boom of the mid-1980s allowed Thatcher to deepen the divisions in the working class by policies such as selling off council houses and selling shares in newly-privatised public companies, whilst weakening trade unions, beginning to dismantle the welfare state and introducing the poll tax. NICKI JAMESON investigates what has happened to the living standards of black and Irish people in Britain in this period and where they stand in Major’s ‘classless society’.

The black population

The ethnic minority population of Britain has risen 18% since 1981.1 Britain has an estimated 2,682,000 inhabitants from ‘ethnic minorities’ (see breakdown below) but this figure, like virtually all data on the subject, excludes the two million Irish people and people of Irish descent resident in the UK. The ‘Other’ category is generally an underestimate also as it usually refers to southern Europeans who are sometimes classified as ‘White’ and sometimes as ‘Other’; in London alone it is currently estimated that there are 100,000 Greek Cypriots and 90,000 Turks, Kurds and Turkish Cypriots.

Table 1 Britain’s Ethnic Minority Communities

|

456, 000 |

W Indian and Guyanese |

|

793, 000 |

Indian |

|

486, 000 |

Pakistani |

|

127, 000 |

Bangladeshi |

|

137, 000 |

Chinese |

|

150, 000 |

African |

|

67, 000 |

Arab |

|

310, 000 |

‘Mixed’ |

|

155, 000 |

‘Other’ |

Under 10% of each ethnic minority group listed above are over 60 years old. 24% of West Indians and Guyanese, 44% of Pakistanis, 46% of Bangladeshis and 31% of Africans are under 15 (as opposed to 19% of whites).

Ethnic minorities make up 5.5% of the population. Over half of all ethnic minority households are in the south east where 9% of the population are from ethnic minorities.2 In inner London 25% are from ethnic minorities.

Employment and unemployment

The Labour Force Surveys for 1989-91 show that ethnic minorities form 4.9% of the economically active population. They are disproportionately concentrated in manual, low-paid and insecure employment. (See Table 2)

Self-employment as a percentage of all those in employment is highest among Pakistani/Bangladeshis, standing at 24%, as opposed to 17% of Indians and 12% of whites.3 In the period 1989-91 32% of Afro-Caribbean and Guyanese men and 40% of Pakistani and Bangladeshi men worked in non-manual jobs, compared to 48% of white men and 59% of Indians. 68% of Afro-Caribbean and Guyanese men and 60% of Pakistani and Bangladeshi men worked in manual jobs compared to 52% of white men.4

In 1989-91 29% of men from black and other ethnic minorities were employed in the distribution, hotels and catering sectors, compared to 16% of white men. Within this category 9% of men from black and other ethnic minorities worked in hotels and catering compared to 2% of white men. In 1991 28% of men in distribution, hotel, catering and repairs earned less than £150 a week. In hotels and catering 47% earned less than £150 a week. (The average for all industries is 10% of the male manual workforce earning less than £150 a week.)

Black women are doubly oppressed. Women’s wages as a whole are about two-thirds of men’s and women in general are concentrated in particular areas of the labour market, eg 25% of all women work in distribution, hotels, catering or repairs. So, although the differential between the wages of black and white women is on average not nearly so marked as that between black and white men (and in the case of Afro-Caribbean women in employment, average earnings are actually slightly higher than for white women as more of them work full time and on shifts) it still holds true that women workers are oppressed as a whole and black women workers doubly oppressed.

Asian women suffer particularly acutely and struggles over the years such as Grunwicks in 1976 and the Burnsall strikers in Birmingham today have exposed appalling working conditions and low pay.

A 1990 Leicester Council survey compared white and Asian workers’ wages and conditions and discovered that 52% of Asian women earned less than £100 for a full week’s work.

According to the Leicester survey the gross median earnings of Asian men in full time work were £160 a week – 82% of white men’s earnings (£196). Asian women in full time work had gross median earnings of £109 a week – 82% of white women’s (£133). Asian men were twice as likely to work shifts as white men (31% compared to 17%). 15% of Asian women worked shifts as opposed to 10% of white women.

Table 2 Economic activity rates by sex, age and ethnic origin

|

|

Age |

% All of working age |

|

||||

|

Ethnic Origin |

16-19 |

20-29 |

30-39 |

40-49 |

50-59/64 |

Male |

Female |

|

White |

66.2 |

81.8 |

84.3 |

87.1 |

69.7 |

87.1 |

64.0 |

|

Black |

40.1 |

72.1 |

76.8 |

86.4 |

69.2 |

75.7 |

29.0 |

|

Indian |

32.9 |

75.0 |

81.8 |

81.6 |

60.5 |

78.7 |

36.9 |

|

Pakistani and Bangladeshi |

35.5 |

50.8 |

53.7 |

40.4 |

35.1 |

67.3 |

31.4 |

|

Other |

40.3 |

62.8 |

68.8 |

82.5 |

73.5 |

77.8 |

40.0 |

|

All |

64.0 |

80.8 |

83.5 |

86.6 |

69.3 |

86.5 |

61.8 |

Unemployment levels are a key indicator of the relative oppression of different sections of the working class. 9% of the white population available for employment is unemployed as opposed to 22% of Afro-Caribbeans and 25% of Pakistanis/Bangladeshis.

The figure for Indian unemployment is much nearer to that of whites: about 12%; this disparity is highlighted in the current Policy Studies Institute (PSI) report, the author concluding that ‘there are various degrees of disparity between racial groups that can no longer be adequately summarised by a simple contrast between “well-off whites” and “poor blacks”.’

Such figures highlight both the difference of class origins amongst ethnic groups immigrating to Britain and the greater presence today than in 1982, when the PSI last produced a report into ‘Ethnic Minorities,’ of a black middle class. Since 1979 successive Tory governments have deliberately fostered such a layer, in the same way they had already created a section of the white working class which has a stake in the system. Table 3 shows the development of this layer.

Table 3 Percentage of male employees in professional, managerial or employer categories

|

Ethnic origin |

1982 |

1988-90 |

|

White |

19 |

27 |

|

Afro-Caribbean |

5 |

12 |

|

African Asians |

22 |

27 |

|

Indians |

11 |

25 |

|

Pakistanis |

10 |

12 |

|

Bangladeshis |

10 |

12 |

These figures indicate that the strategy of creating a middle class has had some success, though again varying according to ethnic groups.

Housing

Studies by the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) and others show that since the 1950s there has been an absolute improvement in the housing conditions of ethnic minorities but there remains a ‘pattern of entrenched housing inequality’.

21% of whites live in detached houses, as do 15% of Indians, 4% of Pakistanis/Bangladeshis and 4% of West Indians. About 6% of white households have more than one person per room, compared to 12% of Afro-Caribbean, 22% of Indian and 43% of Pakistani/Bangladeshi households.5

There is a high level of owner-occupation amongst Asians – 84% for Indians and 67% for Pakistanis/Bangladeshis as opposed to 64% of the general population and 41% for West Indians. But this provides no guarantee of good housing.

A report into Rochdale noted that 95% of Asian residents live in the poorer central areas of Rochdale where the housing conditions are among the worst and the majority live in pre-1919 terraced housing. A 1988 CRE report into Tower Hamlets showed that Bangladeshis were more likely to be allocated the worst housing, ended up in the poorest temporary Bed and Breakfasts (86% as opposed to 66% of whites), waited longer than whites to be housed and were less likely to be rehoused quickly after acts of fire or vandalism. Of three estates examined, the two with the lowest housing standards housed five times the number of Asians as would be expected given their proportion in the borough’s population.6

Tower Hamlets Liberal Council made itself infamous in the 1980s by its refusal to house those it claimed had made themselves ‘intentionally homeless’ by leaving Bangladesh. Camden’s Labour Council later took the same approach to the Irish community and both Councils have been forced to deal with waves of militant opposition to their policies. In 1984 Bengali families occupied Camden Town Hall and forced the council to move them from Bed and Breakfast and change its policy on homeless families. In 1988 Bethnal Green church halls became public sanctuary to families threatened with eviction by Tower Hamlets.

In April this year Tower Hamlets obtained a court ruling that stated a local authority is entitled to investigate the immigration status of a homeless person who has applied for accommodation and has no legal duty to provide accommodation for an applicant who it discovers is an illegal immigrant who has entered the country fraudulently. This is more complex than it sounds, as a man, for example, may enter the country legally and be housed legally. In order to bring his wife and family over, he will have to provide assurance that there is adequate accommodation. But having made this assurance, if the accommodation situation becomes intolerable when the family arrives and they ask for larger accommodation, they can then be considered as illegal immigrants. A question of housing once again becomes an issue of immigration status.

Another CRE investigation into Liverpool Council in 1989 found white people were twice as likely as black people to be allocated a house, four times as likely to get a new house, twice as likely to get a centrally heated house and four times as likely to get their own garden.

In the private rented sector a 1990 CRE survey revealed that 20% of agencies discriminated against black people.

Homelessness

Black people are disproportionately affected by homelessness. In 1989 Birmingham Housing Aid Services reported that 72% of the single homeless people and 44% of homeless families it saw were black.7

‘Today 40% of London’s 250,000 homeless population are from ethnic minorities’ … black people account for at least half of this total and rising. That’s at least 20% when black Londoners comprise a mere 8% of the capital’s total population.

‘Yet walk around London streets and you’ll be hard pressed to find a black person sleeping rough or begging for cash.’

‘That’s because black people form the majority of London’s hidden homeless. Look in squats, derelict buildings, hostels, temporary accommodation, night shelters, mental institutions and friends’ floors and you’ll find them.’ (Nick Mathiason and Allister Harry – ‘Hidden Homeless’ The Big Issue April 1993.)

Irish people

Irish people are the largest ethnic group in Britain. There are over 2 million Irish people and people of Irish descent. There have been three main ‘waves’ of Irish immigration – 1800-50, 1940-60 and more recently in the 1980s when half a million people left Ireland.

The majority of Irish immigrants are 16-25, single and live in London. 50% of all Britain’s Irish community live in the south east: 32% in Greater London alone. Irish people are the only ethnic group whose life expectancy decreases on coming to Britain.

Irish employment is concentrated in insecure and low-paid work. Irish people are over-represented in the building, domestic, shop, hotel, catering and unskilled industrial sectors. They face obvious discrimination when applying for jobs. These are just a few examples of cases which were actually taken to industrial tribunals:

1989 – Boots refused an Irish woman a job interview because she was Irish and ‘likely to get homesick’ and leave.

1990 – The Post Office asked an Irish man about his nationality, followed by ‘Do you have a problem with drink?’

1990 – A temporary secretary was offered a permanent post in a private firm. The offer was later withdrawn on the grounds that her nationality was a ‘security problem’.8

Unemployment among the Irish is second only to Afro-Caribbeans (1981 census figs). The level of homelessness is high and there is discrimination in housing departments against Irish people, shown at its most virulent by Camden Labour Council’s repatriation policy. The Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) is used against the Irish population both for harassment and for intelligence-gathering. Irish people are the only group named specifically in the Act. 97% of those arrested are released without charge. Despite all the Race Relations and Race Discrimination laws passed by British governments since the days of ‘No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs’ signs in windows, the PTA is blatant institutionalised racism, the continuation in Britain of colonialism and imperialism.

Racist immigration policy

Table 4 Balance of immigration/emigration (yearly average)

|

1977-81 |

36,000 out |

|

1982-86 |

18,500 in |

|

1987-91 |

17,800 in 9 |

The average yearly immigration between 1987-91 was 139,300. Neither this figure nor those above includes migration to and from Ireland but does include movement of British passport holders, resident for a year or more abroad.

The net balance of migration into UK in 1991 (again excluding from Ireland) is: total – 27,600; from Indian subcontinent 15, 700; from other ‘New Commonwealth’ countries – 14,300.

There are 612,000 holders of Irish nationality living in the UK, two-thirds of the total of EC nationals.

In 1991, 54,000 people were accepted for settlement in the UK, 1,000 more than in 1990 but 27,000 less than in 1976. Of those accepted in 1991 57% were spouses of immigrants already here and 17% were children. Of all accepted, 27% were from the Indian sub-continent, 20% from the rest of Asia, 18% from Africa and 13% from the Americas.

Many of the people now seeking residence in Britain come not because they are seeking work but because they are fleeing persecution, famine, war or other natural or man-made disasters. Britain’s claim to give the persecuted a safe haven has always been a myth. In 1938 visa controls were introduced for Austrian and German citizens, effectively excluding Jews fleeing Nazi persecution; in 1985 – the first time a Commonwealth country had a visa requirement imposed on it – for Sri Lankan citizens, coinciding with state terror against Tamils. Since then visas have been introduced for people from Iraq, Iran, Somalia, Zaire, Ghana, Turkey, Bangladesh, India and Nigeria.

The number of people seeking asylum increased more than tenfold between 1986 and 1991 but halved in late 1991/early 1992 due to drastic changes in the law which greatly increased the difficulty of registering an application in the first place. (See FRFI 111 – ‘Fortress Europe and the Asylum Bill’)

The backlog of asylum applications was nearly 70,000 by 1991. Of those processed that year, only 1 in 10 was found to have a ‘well-founded fear of persecution’, as defined by the 1951 UN Convention, and granted asylum.

This February Karamjit Singh Chahal, a campaigner for Sikh independence who had been resident in Britain for 20 years and has two children who were born here, lost a fight against a government decision to deport him to India. He had spent two and a half years in Bedford gaol. He maintained in court that he faced arrest and torture if deported, but the judge ruled that the Home Secretary had acted reasonably by ordering the removal of Mr Chahal in the interests of ‘national security’ and ‘the international fight against terrorism’. The UN criterion was clearly irrelevant as the judge ruled that Clarke had ‘clearly evaluated the risk of torture against the risk to national security and decided that the latter outweighed the former’.

Five Alevi Kurds staged a hunger strike outside the Home Office in freezing weather in January/February to protest against intolerable delays in considering their asylum applications. The men were deported in 1989 but brought back into Britain in 1991 when they began High Court proceedings against these deportations. Without their status as refugees confirmed, they could not bring their families to Britain from Turkey.

The 1971 Immigration Act stipulated that wives and children of Commonwealth citizens could only enter the UK if a ‘sponsor’ could support and accommodate them without recourse to ‘public funds’. In 1985 ‘public funds’ were formally defined as supplementary benefit (now income support), housing benefit, family income supplement (now family credit) and housing under Part III of the 1985 Housing Act (Housing the Homeless). The ‘sponsorship’ is only legally binding in a minority of cases but many people are misled into believing it is universally applicable.

Living with British racism

As well as suffering discrimination in economic and social spheres, black people have been singled out for attack by both the state apparatus and by racist groups and individuals. The relationship between state sponsored racism and that of unofficial racist groups may be direct or indirect but its effect is plain: racist attackers are rarely caught or punished whereas if black people organise to defend themselves they are dealt with severely.

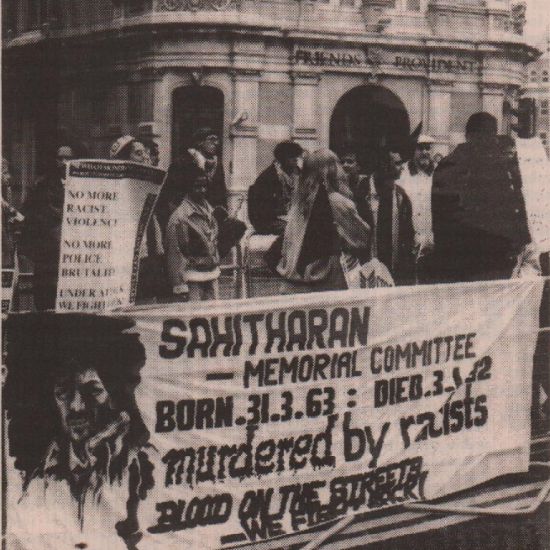

Between January 1970 and November 1989 74 people in Britain died as a result of racially motivated attacks. Since the beginning of 1992 at least nine people have been murdered by racists. They include:

Rolan Adams – murdered in Thamesmead, age 14. After the murder, carloads of skinheads continually harassed his family. Three months later Orville Blair was murdered in the same area.

Rohit Duggal – stabbed to death in a take-away shop in Plumstead. The police said they

did not consider the incident to be racially motivated.

Ruhullah Aramesh – an Afghan refugee, killed by a gang of up to 15 people outside his home. The attack was so blatantly racist that even the right-wing Evening Standard carried the one-word ‘Racists’ across its front-page and the police described the murder as a ‘racially motivated case of extreme brutality’.

Stephen Lawrence – age 18, murdered in south London on 22 April 1993 (the fourth person in that area in 2 years).

There is a significant level of underreporting of racist attacks. Police figures claim there are 7,000 attacks each year. An EC report argued the real figure could be 10 times higher. A London Borough of Newham report in 1987 argued that the level of racial attacks was 20 times higher than the police figures. A May 1991 survey for Victim Support, backed by the Home Office, estimated that the number of race attacks recorded by the police in England and Wales (3-6,000) represented 2-5% of the actual total.11

These are two examples from the daily catalogue of barbaric attacks:

- the firebombing of the house of David Singh, Britain’s first Asian professional snooker player.

- the death of the 68-year old white neighbour of a Bengali family who choked to death after attackers who had been harassing the family for four weeks set fire to the top floor of an Isle of Dogs tower block. The young mother of the family had had a knife and gun brandished at her through her letterbox in previous incidents.

In every one of the following categories of crime, black people were more likely to be victims than white people: household vandalism, burglary, vehicle vandalism, theft, assault, robbery, threats. In some categories twice as likely.12

Black people who defend themselves against racists are likely to end up punished either along with their attackers, like black TV reporter Brian Moore, who was gaoled for Affray, or instead of them like Satpal Ram who is serving a life sentence for murder after defending himself against a gang of six white men.

Racist police

While attacks by civilian fascists are undoubtedly on the increase, black and Irish people in this country continue to be murdered by the state in prisons, police stations, mental hospitals and on the streets.

In 1991 Ian Gordon, a young black man with a history of mental illness, was hunted down by the police in Telford, Shropshire for four hours before being shot dead. He was carrying an unloaded air pistol. In 1985 Cherry Groce was paralysed when armed police raided her home and shot her. Cynthia Jarret died of a heart attack during a police raid on her home. These two attacks sparked uprisings in Brixton and Broadwater Farm where the black community had already had its fill of surveillance, stop and search, raids, assaults, arrests for no reason and general harassment.

In 1992 Malkjit Singh Natt, with support from the Newham Monitoring Project, exposed British police racism in a manner which echoed the Rodney King case in the US. While being arrested, racially insulted and physically assaulted by Newham police in January 1991, Mr Natt managed to tape-record the incident. However, as with Rodney King, cast-iron proof did not automatically lead to justice. Even following his trial, national publicity of the tape and a further appeal hearing, Mr Natt still stands convicted of assaulting a WPC, a charge for which there is no medical or other evidence, and the two PCs who abused and assaulted him were docked one day’s pay and are still on the beat.

Deaths in custody

From April 1969 to January 1991, 75 black people died while in police or prison custody, a figure remarkably similar to that for racist murders during the same period. In only one case has there been a successful prosecution and only one family of a dead person has received compensation.

In October 1992 Omasase Lumumba, the nephew of the late great Zairean President, Patrice Lumumba, died in Pentonville prison, held down by prison officers in a strip cell. He had been arrested for allegedly stealing a bicycle, not charged but held in custody while his asylum request was being investigated.

Whose mental health?

In 1991 Orville Blackwood became the third young black man to die in Broadmoor maximum security mental hospital since 1984 after forcible sedation. Black people who are ‘sectioned’ are far more likely to be compulsorily referred to psychiatric hospitals than white people – in 1984/5 black people formed 36% of those given hospital orders with restrictions and 32% of those given hospital orders without restrictions. Second generation Afro-Caribbean men aged 16-29 are 16 times more likely to be diagnosed as schizophrenic than the average for the population as a whole. One in five ‘patients’ at Broadmoor is Afro-Caribbean and one in three of those is locked up in high security, as Orville Blackwood was. The rate of admission to mental hospitals is also disproportionately high amongst the Irish community.

Racist courts

Black people awaiting trial are more likely to be refused bail than white people and far more likely to have conditions imposed on their bail. Black men receive custodial sentences twice as often as their white counterparts. One in 10 black men has already been locked up by the time he is 21. Social enquiry reports before sentencing are far less likely to be requested in the cases of black defendants.

Prison population

On 30 June 1990 16% of male prisoners were known to be from ethnic minority groups, compared to 14% on 30 June 1986. 28% of the female prison population was known to be from ethnic minority groups, compared with 18% in 1986. Compare the percentages of the prison population who are black or from ethnic minorities to the 5.5% of the British population as a whole and it is only possible to conclude that we live in an extremely racist society.

And getting worse

As the crisis of British capitalism deepens so does the oppression of black people. They suffer discrimination which keeps them out of employment or if working, holds them in the most vulnerable sectors of the job market. As the welfare state is cut so too are many jobs done by black people and many services which they rely on more heavily than white workers. As resources in the state sector are squeezed the more economically and politically privileged sections of the population grab what is available. It is black children who end up in the sink schools and black families who end up in the non-fundholding GP practices.

When we published ‘Racism, Imperialism and the Working Class’ 14 years ago, we argued that capitalism could not and would not overcome the racist oppression of black people. The facts have borne this out. A slightly larger black middle class may exist today but the overwhelming majority of black people remain not merely in the ranks of the working class but forced into its lowest layers. From there they have continued to send out their message, sometimes loud, sometimes muted, that they will fight back against racist Britain.

1 Trevor Jones Britain’s Ethnic Minorities. Policy Studies Institute 1993.

2 Social Trends 1993, taken from Labour Force Surveys 1989-91

3 Social Trends.

4 Carey Oppenheim Poverty the Facts. CPAG 1993.

5 PSI Report.

6 ‘Race’ in Britain Today. Richard Skellington. Saga Publications 1992.

7 Race and Housing. Shelter Fact Sheet.

8 Joan O’Flynn ‘The Irish in Britain – Profile of a hidden experience‘. The Runnymede Bulletin, Apri11993.

9 International Passenger Survey. Quoted in Social Trends.

10 Home Office figures, quoted in Social Trends.

11 ‘Race’ in Britain Today.

12 British Crime Survey.