FRFI 140 December 1997/January 1998

Every measure of health status shows that the working class suffers more ill health than the middle class. Infant mortality rates, life expectancy, frequency of debilitating diseases, incidence of mental health problems, all are worse for the poor. Yet how will New Labour deal with this? By reorganising the NHS so that it becomes a nakedly two-tier institution run by the middle class for the middle class. And to reinforce this aim, they will continue to squeeze NHS expenditure and increase charges so as to further exclude the working class from adequate healthcare.

These are the implications of the White Paper on the NHS which the government will shortly publish, but its main proposals have already been widely leaked. The separation between purchasers and providers will remain in the form of ‘locality commissioning’ bodies which will replace health authorities and GP fundholders. Groups of GPs will band together in localities covering populations of about 100,000, and will purchase all healthcare for this catchment area. The purpose of this move is to constrain expenditure on acute hospital services, the most expensive part of this NHS. There will be much talk of a ‘primary care-led NHS’: an NHS whose main purpose is to tackle illness earlier before it requires hospital treatment. In reality, such an NHS cannot exist in a class-divided society except as a two-tier institution, with the middle class paying privately to ‘top up’ their care.

The NHS today: the Tory legacy

Despite their rhetoric, state expenditure rose consistently under the Tories. Although this was mostly to meet the cost of state benefits for the unemployed, spending on the NHS also rose. Yet the increase was insufficient to meet the extra costs of healthcare arising from an ageing population and improved medical technology. Hence in reality, cuts in service became the norm.

In an effort to deal with what had become an annual funding crisis, the Tories implemented the internal market in 1991 as a means to control hospital expenditure. The NHS was split between the providers and purchasers of care. Within five years, every NHS unit had become a Trust, whilst GPs were encouraged to hold their own funds. Such fundholders had control of their own budget and could bargain with hospitals and other provider units in order to buy services for their patients – in practice at the expense of the patients of non-fundholders. By 1997, GP fundholder practices covered the majority of the population.

Compulsory competitive tendering

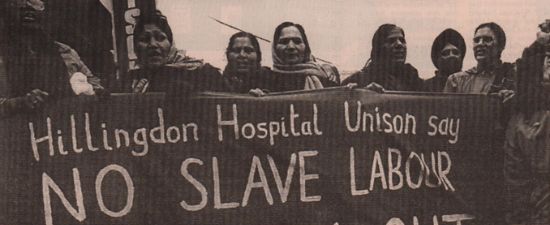

Another strand to the Tory strategy was the introduction of compulsory competitive tendering (CCT) of hospital ancillary services (cleaners, porters, and catering staff), so that these services are run by the company which can provide the cheapest service. This policy arose directly from the role that these workers had played in leading strike action in the 1982 pay dispute. Now working for the private sector, they rarely have a proper contract, let alone union rights, job security, holiday pay, or sick pay, and are paid poverty wages. Union collusion has prevented any significant resistance. An exception are the 52 Hillingdon women (domestics at Hillingdon Hospital in West London), who refused to sign such slavery contracts and were sacked. They are still standing firm, two years on, although UNISON, their union, has abandoned them. Under the New Labour slogan of ‘public-private partnership’, CCT is being extended to other areas: for instance, the medical records department at London’s University College Hospital is now up for grabs. In the ten years following the introduction of CCT in 1984, such working class employment in the NHS fell from 154,000 to 74,000.

A third policy was to reduce the right to free continuing care in the NHS, and couple this with the privatisation of nursing and residential homes. Between 1985 and 1995, the number of places for the elderly in Local Authority homes dropped from 116,000 to 63,000, while the number of places in private homes rose from 80,000 to 167,000. Because spending on such nursing care is means-tested, more than 40,000 old people have to sell their houses to pay.

Yet overall the Tory reforms have failed: they have not cut the cost of hospital service. In particular, they have failed to cut spending on NHS work undertaken by NHS consultants, despite the contracts that enable them to do what they want when they want. Such contracts were a concession made by Aneurin Bevan when Labour established the NHS in 1948, and have now led to a position where full-time NHS surgeons spend little more than half a day each week operating on NHS patients, and a further day in clinic, whilst earning £50,000 and more from the NHS. Many such surgeons have so-called ‘full part-time contracts’, where they are paid 90 per cent of their salary; they then have the right to do as much private work during NHS hours as they like. Some now undertake private operations in NHS hospitals: hospital managers encourage this since it brings in extra cash, although it means that NHS patients once again get pushed to the back of the queue.

In desperation, the Tories then cut capital spending on the NHS from £1.9 billion in 1995/96 to £1.3 billion in1997/98, introduced the Private Finance Initiatives (PFI), and then used the Treasury to stop any schemes from going ahead. Although the Tories trumpeted this as a major success, not one major PFI-financed hospital building project was approved before they were kicked out of office.

Labour’s plans

New Labour, like the Tories, want to cut spending on the NHS. Even before the election they announced their commitment to existing Tory public spending plans, the most draconian ever for the NHS. They proposed no net increase over a three year period: spending would rise by only 0.8 per cent from 1996/97 to 1997/98, stand still for 1998/99 and fall by 0.7 per cent in 1999/2000. Minimally, there has to be an annual increase of 3 to 4 per cent per annum (equivalent now to about £1.5 billion) to maintain a given level of service. The spending plans would bring completely unprecedented cuts of at least 10 per cent over a three year period.

This position is untenable at present: by raiding other budgets Labour has ‘found’ £1 billion for 1998/99, and £300 million to avert a winter bed crisis. But already the government has reneged on its pledge to ‘cut NHS waiting lists by treating an extra 100,000 patients by releasing an extra £100 million saved from ‘red tape’. There are now 1.2 million people waiting for their operations. The number of people waiting over a year has increased fourfold, and 388 people have been waiting longer than 18 months compared to nine people a year ago. The number of emergency admissions continues to grow, contributing to a further lengthening of waiting lists; because emergencies are more expensive, NHS Trusts are forced to reduce the number of waiting list patients they treat still further. The Secretary of State for Health, Frank Dobson, admitted that the government would not be able to fulfil its election pledge in the ‘short term’.

A new deal for the middle class

Waiting lists will not shorten unless consultants’ contracts are reformed. Yet there will not be a word about this in the White Paper, because whilst consultants carry out so much private work, the middle class can jump the queue. And this is really what Labour’s new NHS is about: a deal for the middle class where they do not need to pay taxes for a proper health service for everybody, but use their privileged position to get one for themselves. It is estimated that if all surgeons operated just two days a week for the NHS, waiting time would fall to that of the private patients. But this would mean tackling consultant power, which Labour will not do.

This corruption, which for working class people is a matter of life or death, will continue. Consultants are completely unaccountable (except to their wallets): even when they kill people, they cannot be removed for years. 29 out of 53 child patients died during heart operations undertaken between 1990 and 1995 by surgeon James Wisheart and two other colleagues in Bristol, a mortality rate of 60 per cent – the norm for surgeons doing similar work elsewhere was 14 per cent. For years this situation was tolerated; Wisheart was a hospital medical director, and got full support from his Chief Executive. A surgeon’s accountability is shrouded in the same secrecy as their manipulation of the system for personal gain.

Creeping privatisation

Franke Dobson said in September that most elderly people would prefer to recuperate at home. This is true – pro-vided that they have an appropriate home and the support that they need. But if they are poor, they probably don’t; but then they are not part of Labour’s equation. Estimates say that 7,000 elderly people are ‘unnecessarily’ in hospital due to lack of other suitable arrangements. While hospital bed numbers have been cut, there has not been the compensatory rise in community provision. Further dependence on the private sector is fostered, with social services having to pay. Social services budgets around Britain have been cut by an average of £2.5 million per authority for 1997/98. The government is not intending to end means-testing of payments towards residential and nursing home costs.

Locality commissioning, when it arrives, will be a means of handing more power to GPs to cut hospital spending on the working class. Their collectives will control over 90% of the NHS’s £43 billion annual budgets. With 500-600 such collectives, as compared to the 190 Health Authorities at present, there will be plenty of opportunities for the middle class to pick up management jobs – there will be no reduction in bureaucracy or managerial layers.

Labour will continue with PFI and privatisation – their key-note of ‘public-private partnership’ is a clear statement of purpose. An extension of charges is clearly on the agenda. Frank Dobson recently refused to rule out the introduction of charges to see a GP – after all, Labour would not want working class people wasting such important people’s time. The two-tier service is coming closer, and the middle class has been softened up for it: a recent survey of 1,730 hospital doctors by the newspaper Hospital Doctor, found that 62% agreed people should be charged for certain aspects of their care, and 88% believed charges were inevitable.

Rationing is now the name of the game, although it is called ‘priority setting’. It meant that for a period last winter, Hillingdon closed its doors to any patient over 75. It means that Oxfordshire Health Authority operates a ‘preferred waiting time’ system: it tells the Trusts it contracts with how much time a patient should spend on a waiting list. Hence it says a neurosurgery patient must wait 12 months for treatment, even though hospital waiting lists are much shorter for this specialty: it says it cannot pay for them to be treated any earlier. Of course, if you go private…

The fightback

In Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 128 (January 1996), we wrote that a future Labour government would be equally committed to ‘priority setting’, and that ‘it is but a short step from

supporting grant maintained schools to the introduction of an equally overt two-tier system in the NHS. It is a matter of time before they take it openly’. That time is now approaching. The only class which can lead any resistance is that which will be hit most by such a move – the working class. We cannot rely on the trade unions – although UNISON organises thousands of low-paid workers, in practice it only represent its more privileged members, and it has shown its true colours through its betrayal of the Hillingdon Hospital strikers. Nor can we rely on the various professional associations, since they will be more concerned to protect their narrow sectional interests. The resistance has to be led by the working class organising in their communities, since only they have a consistent interest in preventing the privatisation of NHS services.

Hannah Caller and Robert Clough