Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No. 127, October/November 1995

‘The harvest is past, the summer is ended, and we are not saved.’

THE PROPHET JEREMIAH

A hurricane threatens to blow through the world’s financial system. Not since before the Second World War have the portents looked so ominous for international capitalism. A mountain of debt overhangs a stagnant production base. Vast speculative sums send currencies careering on a switchback ride. Something big and very dangerous is happening. TREVOR RAYNE examines the prospect of a meltdown.

Tom Wolfe’s novel The Bonfire of the Vanities has Wall Street bond trader Sherman McCoy, ‘salary like a telephone number’, ‘Master of the Universe’, trapped by circumstances he cannot understand or control. Every way he turns disaster encroaches on him, a disaster mirrored all around in the crazy, bizarre ruination of New York City. The book was published in 1987, the year $500 billion was wiped off Wall Street shares. McCoy and New York are allegories of the decline of the dollar and the US economy.

Commenting on the 16 September 1992 debacle when sterling left the Exchange Rate Mechanism, despite the Bank of England spending billions, Samuel Britton wrote that it was as if the Chancellor of the Exchequer ‘had personally thrown entire hospitals and schools into the sea all afternoon’. The former chair of the US Federal Reserve Paul Volcker, describing how exchange rate instability makes rational investment decisions impossible, remarked: ‘The answer, to me, must be that such large swings are a symptom of a system in disarray’.

‘Disarray’: a monument to banking finesse, as though a tie, not quite straight, needed adjusting. The truth is triumphant capitalism is in chaos.

We are in a period of renewed inter-imperialist rivalries centred on the USA, Japan and Germany. In 1987 the USA sounded the trumpets of impending trade war with Japan. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc 1989-91 the political and military restraints on Germany and Japan that benefited US capitalism loosened. While the USA footed the defence bill for their protection, German and Japanese capitalists accepted US trade and exchange rate policy and subsidised the dollar. Now this factor is diminished, revealing sharply that capitalism has no anchor country, no anchor currency, no overriding stabilising power such as it had in the last century when Britain and sterling performed this role, or in the period after 1945 when the USA and the dollar were the anchor.

The US’ economy has weakened relative to Japan’s and Germany’s. The dollar, the main currency for world trade, no longer serves so much as an international store of value as a weapon wielded for the benefit of US exports and capital. The loss of an anchor, the reduced US ability to cajole and coerce, adds to the financial instability.

The fantastic sums involved in currency speculation ($600 billion a day in 1990, $1 trillion a day today) feed on and add to the instability. From speculation being a bubble on the back of production, production has become a bubble on the back of speculation. $1 trillion a day is 20-30 times the amount of trade in goods plus services.

If the world’s most powerful governments act in concert they can manage $14 billion a day to combat speculators. Combined industrialised countries’ currency reserves are $550 billion, half the daily trading volume in exchange deals. Once, speculators listened to central bankers for hints on where to bet, now George Soros, fund manager and speculator, utters that the franc and Deutschmark will fall and they fall. A Master of the Universe.

In 1992 Soros bet $10 billion on the Deutschmark against the pound and lira. He made $2 billion profit in two weeks!

This loan-funded speculation has grown precisely as capital accumulation, as investment in production, has slowed, particularly in the USA and Britain. Speculative capital grows as capital decays. The Harvard Business Review estimates that for every dollar or its equivalent circulating in the world’s productive economy $20-50 now circulates in the world of pure finance. Money making money in the blink of an electronic eye. This money is a parasitical claim to real wealth.

As capital accumulation has slowed, so governments have been forced to increase their borrowings to pay for welfare, education, defenseless. In 1978 public debt of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (industrialised) countries averaged 40 percent of Gross Domestic Product. In 1988 it was 54 per cent and 1994 70 per cent. Governments borrow from giant banks, investment and pension funds and multinational companies that move money through the speculative markets. They borrow by issuing bonds.

With increased government reliance on borrowing so dependence on the speculative funds grows. Evermore profitable rates have to be offered consuming more and more government revenues: thus Norman Lamont throwing hospitals and schools into the sea. Last year the US bond market crashed as the dollar fell against the yen. Investors took money out of dollar-denominated US bonds. To repair the bond market long term interest rates were raised. ‘Hot money’ retreated from Mexican investments back to the higher US rates. A run on the Mexican peso followed. Stock markets around the world wobbled. The biggest international rescue of all time, almost $50 billion, was organised to steady the peso. $50 billion of hospitals and schools thrown down the mouths of speculators, while the Mexican economy shrinks five per cent this year and armed guards are posted outside the department stores.

‘If recoveries do not emerge soon, bond and currency markets will force cuts in real public expenditure, shocking millions who have staked their lives on the promise that politicians would protect them from economic difficulty’.

Thus speak investment advisers. They cite Sweden, held up like a trophy, where speculation forced government spending cuts of 20 billion krona in a year to ward off a banking collapse, equal to a quarter of Swedish expenditure on health. In 1993 speculators turned on the French franc, The German and French central banks spent $50 billion defending it. These are real reductions in governments’ financial resources. French foreign currency reserves fell $17 billion in a week. Where did the money go? Primarily to French banks, investment funds etc.

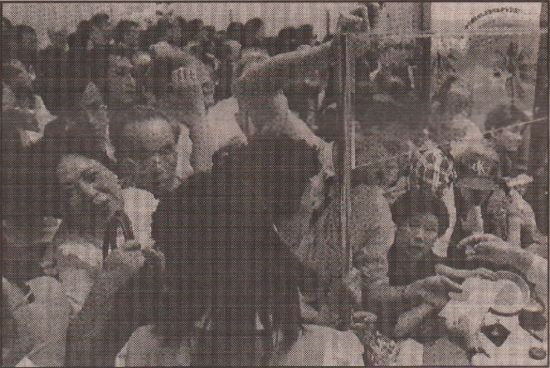

Panicked depositors stormed the Kizu Credit Union, Japan

Crises

For 400 years financial crises erupted in the capitalist system every ten years or so. Periodic crises reflect a crisis in accumulation where profitable investment opportunities dry up, with an over-production of capital driving down the rate of profit and intensifying competition for world markets and resources. Excess capital has to be exported or deployed on the stock market and in speculation to avoid a profits collapse. The top six US banks derive 40 per cent of their total profits trading currencies and securities. Similar proportions obtain for UK banks. Speculation drives up asset prices way beyond what the levels of income they generate should warrant, leading to stock market, derivatives, bond or currency booms. This is accompanied by scrambling for markets and investments overseas.

In the past ten years foreign direct investment by multinationals has quadrupled, twice the growth in world trade. Portfolio investment (share holdings) in developing countries increased seven fold since 1990. UK overseas investment doubled from 1991 to $30 billion in 1994. This is money seeking returns of 20-30 per cent, twice those expected in Britain.

This export of capital and speculation, which such as Will Hutton condemn as the ‘short termism’ of the City, is symptomatic of a crisis of accumulation, of profitability, of decaying and parasitical capitalism, of imperialism.

1929 and today

Some features of the 1929 Crash are relevant to understanding today.

The First World War ended London’s domination of international finance without then establishing New York as successor, just as today the dollar diminishes without the yen supplanting it. In the 1930’s the Bank of England was unable to prevent the Wall Street Crash producing a banking collapse in central Europe, a run on sterling and the ultimate departure of sterling from the gold standard in 1931. Today the central banks, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank are increasingly enfeebled in the face of speculation.

Two financial centres may coexist for a time, but one tends to supplant the other. In capitalism’s history Venice was replaced by Antwerp, Antwerp by Genoa, Genoa by Amsterdam, Amsterdam by London and London by New York. The financial centre serves as lender of last resort, bailing out major bad debtors, holding reserves that reinforce the system. But what happens when the centre cannot hold?

Secondly, the period before the 1929 Crash saw huge trade imbalances resulting in a steep rise in indebtedness. Britain’s debts to the USA rose to half Britain’s national product, Germany’s to one and a half times its national product. The international financial structure depended on credit flows from the USA to Europe. If they stopped the structure would and did collapse. Now, for over twenty years, the USA has depended on capital flowing from Japan and Europe.

In the 1920s the USA was the world’s major creditor nation and it had the biggest trade surplus, Germany was the biggest debtor nation and it had the biggest trade deficit. Today, Japan is the world’s biggest creditor nation and it has the biggest trade surplus. The USA is the biggest debtor nation and it has the biggest trade deficit. A symmetry where only names change.

This imbalance provokes the drive towards protectionism and formation of trade blocs, as it did in the 1920-30s when world trade fell by 65 per cent: the Great Depression.

Thirdly, no country could in the 1920-30s — nor can they now — absorb large surpluses of unsold goods, expand credit at a sufficient rate to counter recessionary trends, ensure exchange rate stability through purchases or sales of currency, impose its will on different governments, for example to collectively inflate or deflate. No one can play the role of locomotive to drive the world economy forward.

Fourthly, in the late 1920s while stock markets boomed agricultural prices fell, particularly in the colonies, and automobile and property prices slumped in the period before the 1929 Crash. Stagnant and falling prices are evident today in Britain, the USA and Japan.

US position undermined

Following World War Two the USA dominated the world economy. At the Bretton Woods Conference in New Hampshire in 1944 the USA, with Britain, planned the IMF and World Bank to regulate international financial relations. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade was intended to regulate trade.

The dollar, the anchor currency, was tied to gold at $35 to one ounce. Other major capitalist currencies were fixed against the dollar with margins for adjustment, to be agreed with the US-dominated IMF. For every $35 presented by a central bank to the USA, the USA had to present one ounce of gold. The USA had up to 70 per cent of world gold stocks to meet claims.

For twenty-five years the capitalist world had growth and stability seldom if ever seen before. Between 1947-67 Britain, France, West Germany and Japan together averaged 6.4 per cent growth per annum, the USA 3.6 per cent. From 1960-73 OECD economies grew on average 4.8 per cent per annum, exports by 8.8 per cent. From 1973-87 economic growth slowed to 2.6 per cent and export growth to 4.2 per cent. For the US economy from 1950-73 the average growth rate was 3.7 per cent, but from 1973-94 it was just 2.4 per cent. Stagnation and instability were returning by the late 1960s.

US-financing of the Vietnam War, together with a series of US budget deficits which heralded the failure of ‘Keynesian’ economics, resulted in a surfeit of dollars circulating relative to gold reserves held. An unofficial rate emerged alongside the official gold rate. Fears that the US Treasury would be unable to meet its gold-dollar commitments led central banks and others to sell dollars.

Between 1971 and 1973 the Bretton Woods currency model unravelled. The dollar was floated in the market and rapidly devalued with gold prices rising to over $800 an ounce. With the dollar devaluing the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC) quadrupled the price of oil. Oil is priced in dollars. The fortunes made by oil producers were deposited in the imperialist banks and lent on to Third World countries. Third World interest payments would meet the industrialised countries’ higher fuel bills.

From 1971 to 1981 Third World debt grew from about $70 billion to $600 billion. Its service costs rose from under $20 billion to over $120 billion a year. By 1993 Third World public and private debt was $1.77 trillion. Absolutely unpayable, even when over 30 per cent of these countries’ export earnings are taken in debt repayments. They can hardly be drained of more wealth. In 1980 one in four Latin Americans lived in poverty. In 1990 one in three. Africa spends four times as much on debt repayments as on health care. Bank lending has been redirected towards the industrial countries and speculation.

The President of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development observed, ‘The signs of America’s relative decline are converging and unquestionable. Japanese productivity is increasing at three times the US rate, while European productivity increases at twice the US rate’. Ten lawyers graduate in the USA for each engineer. In Japan ten engineers graduate for every lawyer. Germany has double the number of scientists and engineers per capita that the USA has. With its relatively decaying productive sector, when the USA expanded state spending in the 1980s with military budgets running up to $300 billion a year to try and break the Soviet Union, the results were predictable. As Fidel Castro observed of the process, it may have broken the Soviet Union but the effort may break the USA next.

Huge state borrowings and trade deficits appeared. Over the past fifteen years the cumulative US trade deficit is $1.68 trillion. By the mid-1980s the USA needed capital imports of $120 billion a year, much of it from Japan and Europe. US national debt rose 342 per cent in the 1980s. Total US debt grew faster than income. By 1992 government borrowing took 70 per cent of all new credit. Total US indebtedness relative to national income is far higher now than it was in 1929. Interest payments on US government debt grew from 10 per cent of GNP in 1980 to 18 per cent in 1992, consuming 62 per cent of federal income tax. This is an unsustainable position. US foreign debt is 200 per cent higher than exports, like Mexico’s in 1982 when the Third World debt crisis broke on the world’s financial markets.

At recent rates of growth US debt repayments on some estimates would consume all the US GNP by 2015. But debt cannot grow faster than output and income forever. There comes a time of reckoning.

In 1985 the USA became the biggest debtor nation and Japan the biggest creditor. To reduce the US trade deficit the major capitalist nations signed the 1985 Plaza Agreement. Central banks would manipulate the dollar down and Japan would expand its economy with low interest rates. Germany and Japan agreed to a devalued dollar rather than face a tariff threat from the USA. The dollar fell 25 per cent and kept on falling as speculators sold it on. The yen and Deutschmark rose, but the US trade deficit was not solved.

Manila, the Philippines: people scavenge in the rubbish

Shadow from Japan

‘In all our careless dealings with other people there comes a time of accounting’ – from a Japanese novel.

Following the Plaza Agreement Japanese interest rates were cut. Surplus capital poured into property speculation. During 1986-87 Tokyo real estate prices rose 80 per cent. A single prefecture was said to be worth more than all of Canada. By the end of 1987 the unit price of Japanese land was fifty times that of the USA.

Soaring land prices served as collateral to expand credit at home and overseas. Japanese banks became the biggest in the world. Loans raised on land went into the share market. In the early 1970s the stock market value of the US firm IBM was greater than the entire Japanese stock market. By the end of 1989 the Japanese telephone monopoly NTT was worth more than the entire German stock market.

Debt piled up on Japanese property and stocks grew far beyond what could be serviced from their yields. Neither the prices nor the dividends were sufficient to pay the debts. In 1990 Nikkei Dow share prices fell 49 per cent. Over 1991-92 Japanese property prices fell 50 per cent. Japanese companies and property owners were left with a massive case of negative equity. Bad debt has mounted; figures vary according to source, but Japanese banks face about $568 billion in bad loans potentially rising in one forecast to over $1 trillion, a quarter of the GNP. Official figures show up to 16 per cent of banks’ loans currently in default. Any further drop in property prices will increase bad debt.

Writing in The Guardian Edward Balls states that the Japanese ‘economy is on the verge of a dangerous deflationary spiral of falling consumer and asset prices, rising debts and falling output unseen in either the US or Europe in the post-war period’. Land and commercial prices continue to fall. In 1995 Sumitomo was the first major Japanese bank to declare a loss since 1945. Five financial institutions have either collapsed or been rescued by the state this year. Japanese industry is operating 21-25 per cent below capacity; factories are closing. The high yen has exacerbated the problem.

Japan’s problems pose a two-fold threat to international capitalism: an international financial collapse and trade war. Eight of the ten biggest banks in the world are Japanese. Japan is the world’s biggest creditor nation. Any change in Japanese banks has implications for the whole world. The newly merged Tokyo Mitsubishi bank has assets of $701.3 billion. Only a handful of countries have national products greater. The UK’s GNP is approximately $900 billion.

Japanese banks accounted for a quarter of the world’s credit creation in the past decade. With the rising yen and falling dollar Japanese companies bought US assets. Japanese investors bought 30 per cent of US Treasury long term bonds in the 1980s. They lent to the USA. Considering the scale of US indebtedness, a break in the chain of credits, a withdrawal of Japanese funds, could trigger a row of defaults, credit im-plosion, meltdown.

If Japan were to retaliate against efforts to force it to cut its trade surplus by withdrawing $10 billion from the many billions it has invested in US bonds it would trigger a crash. It is estimated that the Japanese have lost between $350-500 billion on investments overseas since 1985 due to the fall in the dollar. It is not just a domestic banking crisis that might force Japanese investors to sell property overseas to get liquidity that could cause a crash. As the world’s biggest debtor the USA is bound to supply more dollars onto world markets and Japanese investors are likely to sell dollar assets fearing more losses as the dollar fails even further than the 75 per cent it has dropped against the yen since 1985.

Protectionism

‘Flirting with protectionism is flirting with world catastrophe’ – Leonard Silk, former economic correspondent of the New York Times.

Imperialism’s growing instability and imbalances are producing the customary scapegoats and drive towards protectionism. The 1990 Japanese stock market crash was blamed on a ‘Jewish conspiracy’. The 1993 run on the franc blamed by French politicians on an ‘Anglo-Saxon conspiracy’. Le Monde opined ‘German selfishness is the root of the problem’. In 1992 Norman Lamont blamed the President of the Bundesbank for deliberately weakening sterling with reckless remarks. Now we have several European Union finance ministers accusing Britain, Italy and Spain of gaining unfair trading advantage by devaluing their currencies.

The conspiracy of cohorts sharing out profits gives way to a fight of hostile brothers trying to off-load losses onto each other. Since 1990 there have been the following trade disputes: French soybeans versus USA; Japanese rice versus USA; US sugar versus the world; European airliners versus USA; Asian steel versus USA; European Union public work contracts versus USA; Japanese luxury cars versus USA. Opening skirmishes in a trade war.

Responding to a Japanese government statement that the USA should not use protectionist measures US Trade Representative Mickey Kantor said, ‘I’m not interested in theology’. Asked by Le Monde if the European Union should launch a trade war the then President Mitterrand replied ‘If pushed, I hope so’.

Since 1970 the yen/dollar exchange rate has gone from 358 yen to the dollar to 100 yen to the dollar. Still Japan is on target for $146 billion trade surplus this year and the USA headed for a $182 billion deficit. Pushing the dollar down and the yen and Deutschmark up has not solved a thing. That is why trade war is imminent. Japan is so dependent on exports that it will deepen the slump in Japan which will speed the coming of the crash.

Alternatively, pushing the yen ever higher and the dollar further down will likely have the same effect as, for example, the Mazda Motor Corporation estimates it loses $25 million a year for every one yen rise against the dollar. A continuing rise in the yen is likely to have a depressing effect on the Japanese economy leading to more Japanese investment in the Pacific region. A regional confrontation with the USA is foreseeable. However, should the yen fall against the dollar for any length of time, as it has done recently, then the Japanese trade surplus will grow and trade battles with the USA will intensify. A double-bind. Trapped.

This is the context in which the clamour for a Japanese apology for the Second World War is made and in which US President Clinton remembers Hiroshima by saying he would have dropped the bomb too.

A vision of the future

An investment advice firm offers its potential clients a glimpse of the near future.

‘An unstoppable wedge is about to be driven through the heart of Britain. It is a wedge of technology and culture that will divide this nation into two very different parts: the haves and have-nots those who make the leap into the economy of the future and profit, and those who are left behind, trapped in dying areas and a dying economy…

‘In one part, crime will spread. Homes will be boarded up. Gangs of fatherless young men and boys will roam the streets. People will live shorter, meaner, poorer lives. Property prices will fall… entire areas will be abandoned.

‘Sounds like an inner-city ghetto? Think again. This may be your street 10 years from now. Because the same plague that has destroyed the inner cities is spreading to the suburbs…

‘Meanwhile, just a few hours’ drive from these living nightmares will be some of the finest environments ever created on the planet. These enclaves of peace and prosperity will be protected by geography and electronic fortifications…

‘The Death of Public Services … Government budgets will soon be slashed — and that means spending on public services will be cut more than they already have been. Streets will become no more than broken pavement and dirt. Buildings will burn down for lack of fire protection… Private companies will step in to do the work public services used to do. And you’ll be able to profit by investing in them, too…

‘Soon there will be more than 100 different wars being fought around the world. But there is a profit opportunity here, too. One company has recently developed a machine to detect plastic explosives used by terrorists…

‘Retirement savings evaporate… As the pound falls, shares and bonds will come crashing down too. The retirement savings of many millions of people will be ruined…

‘We’re not worried about being politically correct. We don’t make moral judgements. We just aim to make you money.’

This is the barbarism that capitalism has planned for us — we must and we will resist.