After years of school budget cuts, falling wages for teachers in real terms of more than £4,000 a year since 2010 and cuts to support staff and essential social and mental health support services, the education sys-tem in Britain is in crisis, and thousands of the most vulnerable children are being pushed out of school.

On 7 May, Edward Timpson, former Conservative children’s minister, published his delayed landmark review into the rising use of exclusion and specifically why some groups of children are more likely to be excluded than their peers. Timpson’s review showed eight out of ten permanently excluded children come from vulnerable back-grounds – 78% of permanent exclusions were issued to pupils with special educational needs (SEN), those eligible for free school meals (FSM) or those otherwise classified as in need. In the 2016/17 academic year, 7,700 pupils were permanently excluded – equivalent to nearly 40 children a day. Statistics from the Department for Education (DfE) show that the number of under-11s being taught in pupil referral units after being excluded from mainstream education in England has ‘more than doubled since 2011’ (The Guardian, 1 April 2019). This includes 42 under-fives, 28 of them toddlers aged two and under.

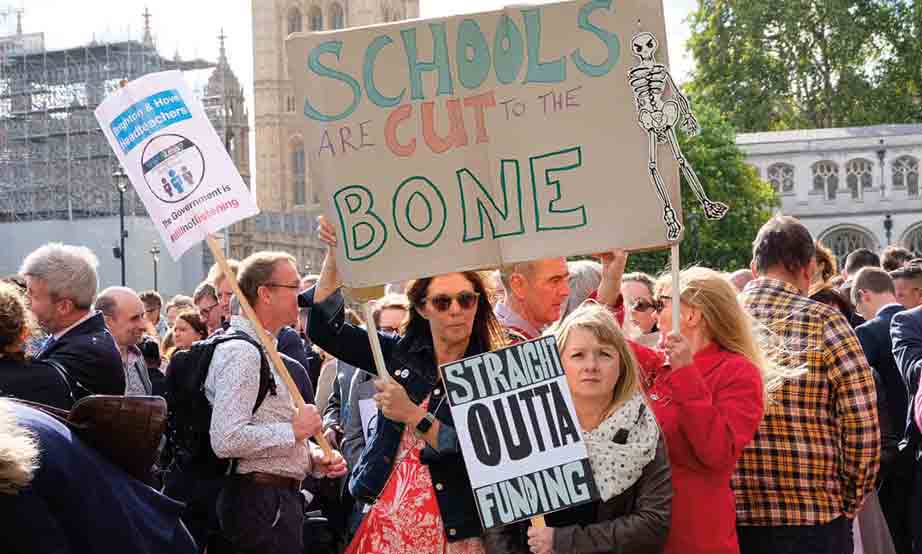

Fight for funding just beginning

The Timpson Review sets out 30 rec-ommendations, including that schools should be held accountable for the educational outcomes of children they exclude, reducing the number of fixed term exclusions a child can receive from the current 45 days in a school year (though a new maximum is not proposed), and several recommendations to curb the practice of off-rolling (removing children from the school register without officially excluding them). It also calls for local authorities to have a greater role in ensuring all children can access education and for a Practice Improvement Fund to cover the cost of building facilities and staffing Alternative Provision (AP) on sites, and for proper interventions for children who need support to continue education in mainstream school.

AP, as described in Timpson’s pro-posals, with specialised staff, tailored facilities and smaller class sizes, would be an ideal way to support children who need it. While the government said it agreed to the recommendations ‘in principle,’ it did not mention the necessary funding for this provision. AP expert Kiran Gill, who was part of a reference group for the review, warned if the government is not held to account then this will be like any other government review ‘where nothing really happens’, and urged ministers to ‘put their money where their mouths are and fight for funding for the most vulnerable’. The review has been criticised by school leaders and organisations for failing to address the underlying problem of utterly inadequate funding for support staff needed for early interventions, which Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders blames for ‘ fuel[ling] the rise in the rate of exclusions in recent years.’

‘Burning injustice’ still ablaze

In FRFI 268, we reported on how pupils with special educational needs, those entitled to FSM, Black Caribbean and Gypsy, Roma and Traveller children were all more likely be excluded both temporarily and permanently. Timpson was commissioned to work on the Exclusion Review in response to the October 2017 Race Disparity Audit, part of Theresa May’s proclaimed ‘abiding mission to tackle burning injustices’ which published data on how ‘people of all ethnic groups are treated across our public services’.

The Race Disparity Audit revealed the double oppression of poor and BAME children in British education, where they are more likely to be from households living in poverty or absolute poverty. While White British and Irish children from better-off households were around twice as likely to attain A*-C in maths and English GCSEs as those who were eligible for FSM, for Black Caribbean pupils in particular attainment was ‘very low overall, with a smaller gap between pupils eligible for free school meals and those not’. But Timpson’s review merely reiterates those findings and fails to analyse the clear endemic racism in this system of exclusion. Six race equality organisations signed a letter in The Guardian criticising the review for ‘the absence of any recommendations relating to racial disparities’ and for failing to address ‘the “burning injustice” of racial inequalities in exclusion rates’.

£10m for ‘crackdown’ on bad behaviour

Rather than deal with the deep crisis in school funding, the DfE has announced a £10m scheme to ‘crack down on bad behaviour’. In charge of this taskforce to advise schools on discipline is Tom Bennett, a former Soho nightclub man-ager appointed as Behaviour Tsar under David Cameron’s Conservative government in 2015. In his first official interview, Bennett derided ‘progress-ivism’ and ‘child-centred learning’ where lessons can include group work, discussion between children and pupils’ personal interests being taken into account, as the cause of disruptive behaviour in class and the rising use of exclusion. He argues this method can work for middle class children who’ve been ‘taken to museums, taught how to shake someone’s hand and say hello’ but that for children who face ‘difficulties’ this is a ‘very good way of maximising misbehaviour’. For these children he wants to create clear boundaries, and use ‘traditional’ teaching such as ‘direct instruction’ where the teacher lectures the class, and drilling where information is repeated by children again and again. The only lesson Bennett thinks working class children need to learn is how to sit down, shut up and respect authority.

If we want to make the education system work towards ‘delivering an equal society’ as Timpson describes, we need look no further than socialist Cuba (see p8), an underdeveloped country, under the ever tightening and illegal US blockade, which manages to guarantee a high level of education for every child. Cuba dedicates more of its budget to education than any other country at 13% of GDP, according to the World Bank, and has a strict 25 child maximum in primary school classes. Capitalism cannot deliver education of this quality for the working class.

Ruby Most

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 270 June/July 2019