Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no.9 March/April 1981

The attitude of British socialists to the Irish liberation struggle over the years until the Partition of Ireland confirmed the strength of opportunism in the British labour movement. Time and time again, so-called socialists betrayed the revolutionary wing of the national movement in Ireland and in so doing undermined the struggle for socialism not only in Britain but also in Ireland. For this reason it is vital that communists draw the lessons of these years in order to fight for a revolutionary programme on the national question today. To do this, we first need to understand why the attitude of socialists to the national question is such a decisive factor in determining the outcome of the socialist revolution. And why the revolutionary struggle for socialism has to be linked up with a revolutionary programme on the national question.

Socialists and the right of nations to self-determination

Many socialists argue against all nationalism on the grounds that they are ‘internationalists’. But this is to turn internationalism into a lifeless and reactionary abstraction. This avoids confronting the reality of imperialism: the fact that the world has been divided into oppressor and oppressed nations and that national oppression has been extended and intensified. It also ignores the split in the working-class movement. One section, the labour aristocracy, has been corrupted by the ‘crumbs that fall from the table’ of the imperialist bourgeoisie, obtained from the super-exploitation and brutal oppression of the people from oppressed nations. The other, the mass of the working class, cannot liberate itself without uniting with the movement of oppressed peoples against imperialist domination. The main consideration for the socialist revolution today is a united fight against the imperialist powers, the imperialist bourgeoisie, and their bought-off agents in the working-class movement. This means the working class fighting in alliance with national liberation movements to destroy imperialism for the purpose of the socialist revolution.

The unity of all forces against imperialism can only be achieved on the basis of the internationalist principle ‘No nation can be free if it oppresses other nations’. This is expressed through the demand of the right of nations to self-determination. Far from being counterposed to the socialist revolution, it is precisely to promote it that communists are so insistent on this demand. This demand recognises that class solidarity of workers is strengthened by the substitution of voluntary ties between nations for compulsory, militaristic ones. The demand for complete equality between nations, by removing distrust between the workers of the oppressor and oppressed nations, lays the foundation for a united international struggle for the socialist revolution. That is, for the only regime under which complete national equality can be achieved.

‘To insist upon, to advocate, and to recognise this right (of self-determination) is to insist on the equality of nations, to refuse to recognise compulsory ties, to oppose all state privileges for any nation whatsoever, and to cultivate a spirit of complete class solidarity in the workers of different nations.’ (Lenin)

Our ‘internationalists’, when confronted with these arguments, are forced to adopt yet another line of approach. Of course, they say, we support the right of nations to self-determination, but as ‘socialists’ we are opposed to bourgeois and/or petit bourgeois nationalism. Once again, they avoid the reality of national oppression. They ignore the fact that, as Lenin pointed out, the actual conditions of the workers in the oppressed and in the oppressor nations are not the same from the standpoint of national oppression. The struggle of the working class against national oppression has a twofold character.

‘(a) First, it is the “action” of the nationally oppressed proletariat and peasantry jointly with the nationally oppressed bourgeoisie against the oppressor nation; (b) second, it is the “action” of the proletariat, or its class-conscious section, in the oppressor nation against the bourgeoisie of that nation and all the elements that follow it.’

Let us examine these two points in turn.

In general, all national movements are an alliance of different class forces which unite together for the purpose of achieving national freedom. The bourgeoisie in the oppressed nation supports the struggle for national freedom only in so far as it promotes its own class interests. For this class, national freedom means the freedom to exploit its own working class, to accumulate wealth for itself, to establish itself as a national capitalist class. If, at any point, the struggle for national freedom threatens the conditions of capitalist exploitation itself, the bourgeoisie will abandon the national struggle for an alliance with imperialism.

The working class supports the struggle for national freedom as part of its struggle to abolish all privilege, all oppression and all exploitation – this being the precondition of its own emancipation. The working-class policy in the national movement is to support the bourgeoisie only in a certain direction, but it never coincides with the bourgeoisie’s policy. For this reason, the working class only gives the bourgeoisie conditional support. Insofar as the bourgeoisie of the oppressed nation fights the oppressor, the working class strongly supports its struggle. As Lenin so clearly argued in 1914:

‘The bourgeois nationalism of any oppressed nation has a general democratic content that is directed against oppression, and it is this content that we unconditionally support.’

Insofar as the bourgeoisie of the oppressed nation stands for its own bourgeois nationalism, for privileges for itself, the working class opposes it.

The important thing for the working class is to ensure the development of its class. The bourgeoisie is concerned to hamper this development by pushing forward its own class interests at the expense of the working class. The outcome of this clash of interests in the national struggle cannot be determined in advance. It depends on the concrete context in which the struggle for national freedom takes place.

The guiding light for the working-class movement is clear. The working class rejects all privileges for its ‘own’ national bourgeoisie, and its ‘own’ nation. It is opposed to compulsory ties between nations standing firmly for the equality of nations. In the oppressor nation, the working class can only express this position by insisting on the right of nations to self-determination. And it does this in the interest of international working-class solidarity. A refusal to support the right of nations to self-determination must mean in practice support for the privileges of its own ruling class and its bought-off agents in the working-class movement. Therefore, support for the right of nations to self-determination is the only basis for a united struggle against national oppression and imperialism, and for the socialist revolution. Whether the exercise of this right takes the form of complete separation or not hinges on the conduct of the working class and the socialist movement in the oppressor nation. The history of the Irish struggle for self-determination underlines this.

Marx and Engels had at first expected that the English working class, having overthrown capitalism in England, would then go on to free Ireland. After 1848, however, the English proletariat lost its revolutionary drive and fell under the influence of the Liberals while the national liberation movement in Ireland developed and assumed revolutionary forms. Marx and Engels, therefore, called upon the English working class ‘to make common cause with the Irish’ and support the dissolution of the forced Union of Ireland and England in the interest of their own emancipation. As Marx wrote in January 1870:

‘The transformation of the present forced Union (that is to say, the slavery of Ireland) into an equal and free confederation, if possible, or into complete separation, if necessary, is a preliminary condition of the emancipation of the English working class.’

Whether the dissolution of the forced Union would take the form of complete separation or a free federal relationship would depend on the manner in which it was carried out. A ‘free confederation’ was a possibility if the emancipation of Ireland was achieved in a revolutionary manner and was fully supported by the English working class. Such a solution to the historical problem of Ireland, as Lenin pointed out, would have been in the best interest of the working class and ‘most conducive to rapid social progress’. Such close links between the proletariat in Ireland and England would have played a decisive role in a united international struggle for the socialist revolution in Europe.

However, this was not to be. The failure of the British working-class movement to support the Dublin workers in 1913 made it clear that the interests of the Irish working class could only be advanced through Ireland’s complete separation from Britain. The long-held view of that great revolutionary socialist, James Connolly, had now finally been confirmed. As he argued in 1916 a few weeks before the Easter Rising:

‘ . . . Is it not well and fitting that we of the working class should fight for the freedom of the nation from foreign rule, as the first requisite for the free development of the national powers needed for our class? It is so fitting.’

Socialists in Britain would soon be put to the test. The right of the Irish people to self-determination could only mean for socialists complete separation and, as Lenin argued, socialists could not, without ceasing to be socialists, reject such a struggle in whatever form, right down to an uprising or war. The years to the Partition of Ireland were to show how the working-class movement in Britain failed to support the national struggle in Ireland. Imperialism and war not only split the working-class movement but also divided the national movement in Ireland into a revolutionary and a reactionary wing. The British working-class movement did not support the revolutionary wing of the national movement in Ireland and in failing to do so betrayed both its own interests and those of the Irish working class. It was only a very tiny group of revolutionary socialists who consistently stood for the communist position on the right of the Irish people to self-determination.

Home Rule and the Exclusion of Ulster

The General Election of December 1910 created a parliament in which 84 Irish (Home Rule) Party members held the balance of power between the Liberal/Labour majority and the Conservative opposition. In August 1911 an act was passed limiting the veto of the House of Lords so removing one major obstacle to the passage of a Home Rule Bill. The Liberal government was forced, through pressure from the Irish Party, to introduce a Bill in April 1912 to give a very limited measure of Home Rule to Ireland. In this Bill, the British Parliament retained the sole right to make laws connected with foreign relations, defence and external trade. It retained full control over taxation. It held the power to alter or repeal any Act of the proposed Irish Parliament. While Redmond’s Irish Party enthusiastically supported the Bill, many sections of the national movement denounced it.

The Ulster Unionists began a militant campaign against the Bill. They made it clear that they would ignore the British Parliament and would take over the Province of Ulster instantly if Home Rule came into force. The leadership of this rebellion fell to Sir Edward Carson. Preparations for armed resistance to the British Parliament began. Following the precedent of 1886, Ulster Unionist thugs demonstrated against Home Rule by attacks upon Catholics. On 12 July 1912 two thousand Catholic workmen were driven out of the Belfast shipyards.

Under Carson’s leadership, Unionist paramilitary forces, the Ulster Volunteers, began training openly in the use of arms. Carson repeatedly said that he didn’t ‘care two pence whether it was treason or not’. He knew he could get away with it. After all, Bonar Law, leader of the Conservative Party, in July 1912 in a speech at Blenheim in England in the presence of Carson had said:

‘There are things stronger than parliamentary majorities. I can imagine no length of resistance to which Ulster will go, in which I shall not be ready to support them . . .’

Although Asquith, leader of the Liberal Party, described this as a ‘declaration of war against Constitutional Government’, he took no action against those involved. On 28 September, Carson’s infamous Covenant was drawn up which said that if Home Rule was ‘forced upon us we further solemnly and mutually pledge ourselves to refuse to recognise its authority’. It was signed by nearly half a million Ulster men and women. In December 1912 all those men who had signed it were asked to enrol for either political or military service against Home Rule. The aim was to get an armed force of some 100,000 men. The Liberal government took no action against Carson.

All through 1913 arms were imported into Ulster for use by Carson’s volunteers. Ex-officers and reserve officers of the British Army offered their services to train the volunteers. During March, orders were sent by the Government to the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces in Ireland, General Gough, to move troops from the Curragh camp in the South to Ulster to protect arms depots which it thought were to be raided by the Ulster Volunteers. General Gough and other officers from the British Army said they would resign their commissions rather than serve against Ulster Unionists. The officer class of the army had mutinied. The Liberals refused to take action against them. The army officers had, after all, close links with the English landed aristocracy as well as the leaders of the Conservative Party, that is, they were linked to a significant section of the British ruling class. The Liberals, knowing where their real class interests lay, gave assurances that the armed forces would not be used to crush opposition to the Home Rule Bill. The following month, under Carson’s orders, 35,000 rifles and 2,500,000 rounds of ammunition were openly landed on the Ulster coast. Parliament and the law had been overruled by the officer class of the British Army.

The lessons from this episode are important. The Liberals had no qualms in sending Tom Mann and others to prison in 1912 when they called upon soldiers not to shoot striking workers. The Liberals had, in fact, used armed soldiers against striking workers at Tonypandy in 1910 and Llanelli and Liverpool in 1911. But they refused to confront Carson, Bonar Law and the army officers who mutinied at Curragh. Why did the Liberals allow the aristocratic officers at the head of the British Army to tear the British law to shreds and give British workers, in Lenin’s words, ‘an excellent lesson of the class struggle’? Essentially, because even this mild Irish Home Rule Bill challenged the interests of a significant section of the British ruling class, and threatened to begin the process of undermining British imperialism’s rule in Ireland. And, as Lenin argued:

‘These aristocrats behaved like revolutionaries of the right and thereby shattered all conventions, tore aside the veil that prevented people from seeing the unpleasant but undoubtedly real class struggle . . . Real class rule lay and still lies outside Parliament . . . And Britain’s petty-bourgeois Liberals, with their speeches about reforms and the might of Parliament designed to lull the workers, proved in fact to be straw men, dummies, put up to bamboozle the people. They were quickly “shut up” by the aristocracy, the men in power.’

The Liberals, concerned to maintain British imperialist rule, had no choice. In a period of the growing polarisation of class rule, they could not appeal to the only force capable of putting down the rebellion – the working class – they had, after all, been using the army to put down strikes. They simply gave way to the demands of those who held real power. And real power was outside Parliament.

The Home Rule Bill had been put forward to contain the growing opposition to British rule in Ireland. It was an attempt to use the moderate bourgeois Irish Party as the vehicle for preserving British rule in Ireland in a more acceptable and less naked form. The Ulster Unionists backed by a powerful section of the British ruling class protested. Even at this time to speak of Ulster as though it was overwhelmingly Loyalist was simply nonsense and everyone knew that. After a by-election in early 1913, Ulster’s elected representatives in the House of Commons consisted of 17 Home Rulers and 16 Unionists. Anyway, the issue for the British ruling class was not democracy – then or today. The issue was to preserve British imperialist rule in Ireland and democratic rights would be brushed aside when that was threatened. Lloyd George demonstrated this when, in May 1916, he gave Carson a written pledge that ‘Ulster does not, whether she wills it or not, merge in the rest of Ireland’. Thirty years later this position was repeated by the post-war Labour Government which said:

‘So far as can be foreseen, it will never be to Great Britain’s advantage that Northern Ireland should become part of a territory outside Her Majesty’s jurisdiction. Indeed, it seems unlikely that Great Britain would ever be able to agree to this even if the people of Northern Ireland desired it.’

The Labour Party, faithful as ever to Great Britain, that is, British imperialist rule, gives the game away. Democracy – well, that is for those prepared to be fooled. That is why British rule in the North of Ireland today is defended on the basis of ‘democracy’, that the people in the Six Counties want to preserve the Union with Britain.

In May 1914, the Liberals announced an amendment to their Home Rule Bill which excluded part of Ireland from the operation of Home Rule. Ireland was to be partitioned in order to preserve British rule. The Irish national movement was immediately split. Griffith’s Sinn Féin, the revolutionary Republicans and Irish Labour were totally opposed to the Partition of Ireland. The Irish Party accepted it. The Irish bourgeoisie, represented by the Irish Party, knew that it could only oppose Partition by mobilising the revolutionary forces of the Irish people. Having experienced the revolutionary determination of the Irish working class during the Dublin lock-out, it knew that mobilising such forces would threaten its very existence as a class. Forced to choose between the struggle for national freedom and its own class interests, the Irish bourgeoisie abandoned that struggle and formed a corrupt alliance with British imperialism.

The revolutionary socialist James Connolly completely understood the real meaning of Partition for the Irish working class:

‘Such a scheme as that agreed to by Redmond and Devlin, the betrayal of national democracy of Industrial Ulster would mean a carnival of reaction both North and South, would set back the wheels of progress, would destroy the oncoming unity of the Irish labour movement and paralyse all advanced movements whilst it endured.’

All hopes of uniting workers irrespective of religion and sectarian divisions would be shattered if a part of Ulster were to be separated from the rest of Ireland. Connolly understood all too well how British imperialism had perpetuated divisions in the Irish working class through the union with Britain. He knew why the Protestant working class invariably sides with British imperialism against the national aspirations of the Irish people. He was able to explain why the Protestant working class supported Orange ideology, which was not only hostile to nationalism but also opposed to the interests of the working class. Connolly recognised the basis of these facts in the different social economic and political positions occupied by Protestant and Catholic workers. And it was British imperialist domination of Ireland that was the root cause of these divisions in the working class:

‘. . . the Orange working class are slaves in spirit because they have been reared up among a people whose conditions of servitude were more slavish than their own. In Catholic Ireland the working class are rebels in spirit and democratic in feeling because for hundreds of years they have found no class as lowly paid or as hardly treated as themselves’.

‘At one time in the industrial world of Great Britain and Ireland the skilled labourer looked down with contempt upon the unskilled and bitterly resented his attempt to get his children taught any of the skilled trades; the feeling of the Orangemen of Ireland towards the Catholics is but a glorified representation on a big stage of the same passions inspired by the same unworthy motives.’

The Protestant working class, just like the skilled workers in Britain possessed certain privileges (better wages, better conditions, greater job security, political rights) denied the rest of the working class. The Protestant workers, therefore, feared and opposed the Irish workers’ fight for equality because they thought this would undermine their own position. They likewise accepted Orange ideology and sided with British imperialism because of their privileged position in relation to the Catholic worker. That is why Connolly could argue

‘The doctrine that because the workers of Belfast live under the same industrial conditions as do those of Great Britain, they are subject to the same passions and to be influenced by the same methods of propaganda, is a doctrine almost screamingly funny in its absurdity.’

What prevented basic class interest uniting Catholic and Protestant workers was precisely the Union with Britain. While suppressing the democratic rights of the Irish people as a whole, British imperialism guaranteed certain rights and privileges to the Protestant minority in Ireland. By bolstering the Northern industrial capitalists in Ireland, it guaranteed a relatively privileged position for Protestant workers. The Protestant workers saw their privileged position as a consequence of British rule and that is why they supported that rule.

Connolly understood that independence for Ireland would result in equal rights for Catholic and Protestant workers. And only the loss of its privileged position would allow the ‘possibility of an immense spiritual uplifting of the Protestant working class’. Only in such circumstances would the Protestant working class be able to recognise its real class interests with ‘its brothers and sisters of different creeds’. While British imperialism remained in Ireland such developments were not possible. Partition would block any hopes for the unity of the Irish working class. The Irish capitalists in the South and Orange capitalists in the North therefore had a common interest in supporting Partition.

Such was Connolly’s hostility to Partition that he argued that it should be fought with armed resistance if necessary. He reminded the workers of Belfast how during the Belfast Dock Strike (1907) no officer class resigned when told to shoot down workers and shed blood in Ulster. No Cabinet members apologised to the relatives of the workers they had murdered. British imperialism had an interest in supporting Carson and the Loyalists in order to maintain British domination of Ireland. Without British backing, the Unionists could easily be dealt with. For

‘. . . were the forces of the Crown withdrawn entirely, the Unionists could or would put no force into the field that the Home Rulers of all sections combined could not protect themselves against with a moderate amount of ease.’

It was not for nothing that the British ruling class had turned a blind eye to the arming and drilling of the Loyalists. Indeed, it was only on 4 December 1913, nine days after the inauguration of the Irish Volunteers, an armed force of the Irish Nationalists, that the British Government issued a proclamation prohibiting the importation of military arms and ammunition into Ireland. The Ulster Unionists were reputed to have already between 50,000-80,000 rifles at this time. Then, as today, behind the Protestant armed gangs and thugs were the British imperialist forces. The Liberal Government and Ulster capitalists had a common interest in the exclusion of Ulster, as the best available way to prevent the ‘new unionism’ and the rapidly developing Irish labour and socialist movement from uniting the Catholic and Protestant working class. A divided working class, whilst aiding the Ulster capitalists, also perpetuated British imperialist rule and seriously undermined the possibility of a united socialist movement in Ireland.

The internationalism of the British labour movement was now to be tested. Partition not only threatened to undermine the struggle of the Irish working class, but was also a direct denial of the right of the Irish people to self-determination. The working class in Britain had an internationalist duty to uphold this right and oppose Partition. This was the only possible basis for unity of the Irish and British working class and for a united struggle against their common enemy, British imperialism.

Instead of following the lead of the revolutionary Irish working class, the British labour movement followed the Irish bourgeoisie. It followed Redmond rather than Larkin and Connolly. The British Labour Party ignored resolutions from the Irish Trade Union Congress preferring to adopt the recommendations of the Irish Party. The British Labour Party acted like its British imperialist masters towards the Irish TUC when Irish representatives proposed to establish a separate and independent party. The Irish members requested that political contributions of Irish members of amalgamated unions (British based) be turned over to the Irish Congress to aid the formation of an Irish Labour Party. The British Party refused because, according to Arthur Henderson, the constitution of the Irish Labour Party, unlike the British, did not allow affiliation of socialist and co-operative bodies: the differences made the objectives of the two parties different. The Irish explanation that their different circumstances demanded this, did not move these Labour Party leaders like Henderson so infected with that British imperialist mentality which had such deep roots in the British labour movement. Henderson wanted the Irish Labour Party to be the tail of the British Labour Party.

The Irish Congress executive in 1914 urged the British Labour Party to oppose Partition and, if necessary, to vote against the entire Home Rule Bill in order to prevent it. But the British Labour Party knew better, it followed the lead of the Irish Party – the party of Irish capitalists – in supporting Partition. George Barnes, Labour MP, justified this treachery on the grounds that ‘the Nationalists of Ireland have sent men to Parliament and the Labour men have not’. Connolly’s reply to this will suffice: ‘The love embraces which take place between the Parliamentary Labour Party and our deadliest enemies – the Home Rule Party – will not help on a better understanding between the militant proletariat of the two islands’. Once again, the corrupt and privileged leadership of the British Labour movement joined with British imperialism and the Irish bourgeoisie against the Irish working class. Having betrayed the revolutionary trade-unionism of Larkin and Connolly during the Dublin lock-out, it now betrayed the revolutionary nationalism of the Irish masses. It was now clear that no section of the Irish people, apart from the Irish bourgeoisie, could place any trust in the official Labour movement in Britain. Once again, Connolly’s stand was confirmed; the only way to defend the interests of the Irish working class was complete separation from Britain.

At this point, the first imperialist war broke out. The Home Rule Bill was passed, but was suspended until after the end of the war.

Imperialist War

On the declaration of war the European Socialist movement disintegrated, as socialist parties sided with their own imperialist bourgeoisie. The major exceptions were the Russian and Irish labour movements. Lenin and Connolly were among those very few who stood by the resolution on war passed at the Stuttgart Congress of the Second International (1907). This argued that it was the duty of socialists, should war break out, to use the economic and political crisis ‘to rouse the people and thereby hasten the abolition of capitalist rule’. As Connolly said:

‘Should the working class in Europe, rather than slaughter each other for the benefit of kings and financiers, proceed tomorrow to erect barricades all over Europe, to break up bridges and destroy the transport service that war might be abolished, we should be perfectly justified in following such a glorious example and contributing our aid to the final dethronement of the vulture classes that rule and rob the world.’

And if this did not occur then it was ‘our duty to take all possible action to save the poor from the horrors this war has in store’.

Connolly was among those in Ireland who saw the war as an opportunity to end British rule. ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.’ Connolly, and then Lenin after him, both following in the tradition of Marx and Engels, saw a national revolution in Ireland as a blow delivered against the English imperialist bourgeoisie, which would sharpen the revolutionary crisis in Europe. Connolly proposed as an immediate step that the labour movement should prevent the food that ought to feed the people of Ireland from being exported in ever greater quantities so ‘that the British army and navy and jingoes may be fed’. To prevent the working class in Ireland from starving, it may mean more than transport strikes, if necessary it could mean ‘armed battling in the streets to keep in this country the food of our people’. He continued:

‘Starting thus, Ireland may yet set the torch to a European conflagration that will not burn out until the last throne and the last capitalist bond and debenture will be shrivelled on the funeral pyre of the last war-lord.’

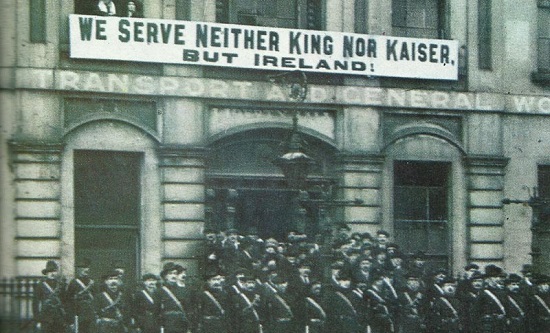

James Larkin, leader of the Irish Transport Union, before he left for America on 24 October 1914 to collect funds for the Union vigorously denounced the war and any Irish participation in it. ‘Stop at home. Arm for Ireland. Fight for Ireland and no other land.’ By the end of August 1914 he, like Connolly, saw that Ireland had now the ‘finest chance she had for centuries’ to free herself from British rule. Addressing 7,000 people in O’Connell Street, he told them that the Transport Union was prepared to do all it could to facilitate the landing of rifles in Ireland. He appealed for recruits to the Irish Citizen Army.

In Ireland, the majority of labour and socialist organisations opposed the war. No representative labour body officially supported the British war effort, and the leading figures of the labour movement were strongly opposed to it. The Dublin Trades Council declared against Irish involvement in the war in September 1914. In Belfast, the anti-war feeling was at its weakest. Whole sections of the Protestant working class were ‘loyal’ to Britain. Nevertheless, Connolly and his supporters fought to win the Belfast workers to an anti-war position, often in a very hostile environment. In this development already can be seen the consequences of the forthcoming Partition of Ireland. For with Partition, the Protestant workers of Belfast would be completely cut off from the anti-imperialist forces of the Irish working class.

On 10 August 1914, the Irish TUC Executive issued a proclamation, ‘Why should Ireland starve?’, and it declared that ‘a war for the aggrandisement of the capitalist class has been declared’ and urged all workers ‘to aid us in this struggle to save Ireland from the horrors of famine’ by means of control of foodstuffs and the prevention of profiteering etc . . . In September 1914, the ITUC executive passed a resolution, sponsored by Larkin, condemning economic conscription. The resolution condemned ‘the insidious and cowardly action of the employers in dismissing men from their employment with a view to compelling such dismissed men, by a process of starvation, to enlist as volunteers’.

While the Irish working class had revolutionary leaders like Larkin and Connolly there would be no Irish labour movement support for Britain’s imperialist war. In fact, the Irish labour movement, after Connolly’s murder by the British, and Larkin’s absence in America, continued to prevent conscription of any kind until the end of the war. On 23 April 1917, with the exception of the Belfast area, there took place the first general strike in the European labour movement against the more vigorous prosecution of the war through conscription in Ireland.

This stand of Irish labour was in sharp contrast to the totally pro-imperialist response in Britain. The British TUC and Labour Party enthusiastically supported the war. On 24 August 1914, they declared that there should be an Industrial Truce for the duration of the war; and on 29 August, the Labour Party agreed to an Electoral Truce and placed the party organisation at the disposal of the recruiting campaign. In May 1915, the Labour MP Arthur Henderson, having already sided with the Irish bourgeoisie against the Irish working class, now joined a War Coalition Cabinet with the most reactionary forces in Ireland, including no less than 8 Ulster Unionists. The Loyalist thug and reactionary, Sir Edward Carson, was made Attorney-General and Bonar Law, Secretary of State for the Colonies. A more calculated insult to the Irish people could not have been conceived. A more destructive blow to any hope of united struggle between the Irish and British workers against imperialism could not have been conceived. Two other Labour MPs, William Brace, of the Miners, and G H Roberts, of the Printers, joined in this filthy act of betrayal by taking junior offices.

The small socialist movement in Britain was not able to make any effective stand against the war. The largest organisation, the British Socialist Party, under Hyndman’s control, wholeheartedly supported an allied victory in the war. It later split and after the Hyndmanites left in 1916, the new leadership, while disowning a chauvinist line on the war, did not elaborate any clear alternative. Leading Labour movement figures such as Keir Hardie, George Lansbury MP (editor of the Daily Herald), Ramsay MacDonald supported the war, once war broke out. Only the tiny Socialist Labour Party and the Women’s Suffrage Federation (later Workers Socialist Federation) developed a revolutionary opposition to the war. There were also small numbers in the ILP who opposed it on pacifist grounds. John Maclean in Glasgow and Sylvia Pankhurst in London were the revolutionary leaders in Britain who maintained the most consistent opposition to the war. It is no surprise that they also gave unwavering support to the Irish struggle for self-determination.

To return to Ireland: the anti-war forces of the Labour movement were soon joined by the revolutionary wing of the national movement. Redmond’s Irish Party necessarily supported the war in alliance with British imperialism. Redmond and his supporters organised recruiting meetings up and down the country in defence of Britain and the Empire. His efforts were supported by the Irish employers, who sacked workers in their thousands in order to force them, by starvation and poverty, to ‘volunteer’ to join the British army. Once again, the Irish bourgeoisie betrayed the national struggle to protect its own class interests. The Irish Party was as ‘loyal’ to Britain as the Ulster Unionists.

The revolutionary wing of the Irish Volunteers led by, among others, Pádraic Pearse, opposed any support for British imperialism. On the contrary, they saw the war as an opportunity to strike a blow for Irish national freedom. ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.’ Redmond’s support for the war led to a split in the Irish Volunteers. A National Convention on 25 October 1914 saw a section of the Irish Volunteers, 12,000 out of 200,000, affirm their determination to maintain a defence force in Ireland, resist conscription and defend the unity of the nation and its right to self-government. Those who remained with Redmond became known as the National Volunteers. Most of the National Volunteers joined the British army.

From the outbreak of war, the Irish Citizen Army co-operated fully with the Volunteers. When Connolly made contact with the Irish Republican Brotherhood, forerunner of the IRA, secretly organised within the Irish Volunteers, the first steps towards the Easter Rising were made. The IRB had also decided on the outbreak of war that an uprising must be organised. They had, in fact, sounded out other nationalist groupings for their views. It is of note that Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin opposed a rising and broke with the IRB and the Volunteers. Pádraic Pearse was made director of the IRB in December 1914. The alliance of revolutionary nationalism and Irish Labour had now been forged. Under the leadership of Pearse and Connolly it carried out the Easter Rising.

Starting from the interests of the working class, Connolly opposed the imperialist war and saw it as an opportunity to free Ireland from British rule. Starting from the interests of the Irish national struggle Pádraic Pearse equally opposed the war and equally saw it as an opportunity to end British rule in Ireland. The alliance of revolutionary nationalism and Irish Labour which was born in the Dublin lock-out came to fruition during the imperialist war.

We have already said that the main consideration for the socialist revolution today is a united fight against the imperialist powers, the imperialist bourgeoisie, and their bought-off agents in the working-class movement. And that this requires the working class to fight in alliance with national liberation movements to destroy imperialism. In the struggle for Irish self-determination the significance of this position is clearly seen. On the one side we see the forces of revolutionary nationalism in alliance with the class-conscious workers in Ireland. On the other the forces of reaction: the Irish bourgeoisie, the British imperialist bourgeoisie, and its agents in the British working class. The defeat of the Irish struggle for national freedom and the working-class struggle for socialism in both Ireland and Britain, was decisively influenced by the failure of the British working-class movement to unite with the Irish national liberation movement against British imperialism.

Continued in part four.

[Material from this article later went on to become part of Ireland: the key to the British revolution by David Reed]

David Reed

March 1981