Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no.99 February/March 1991

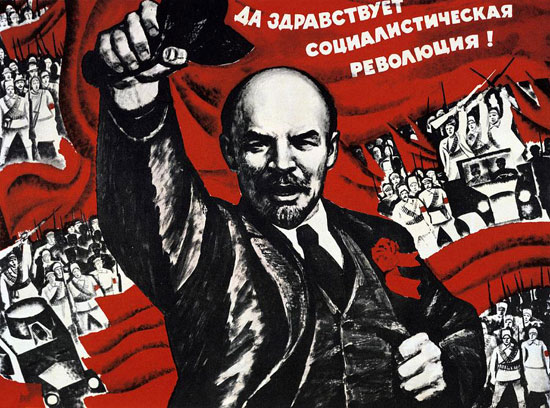

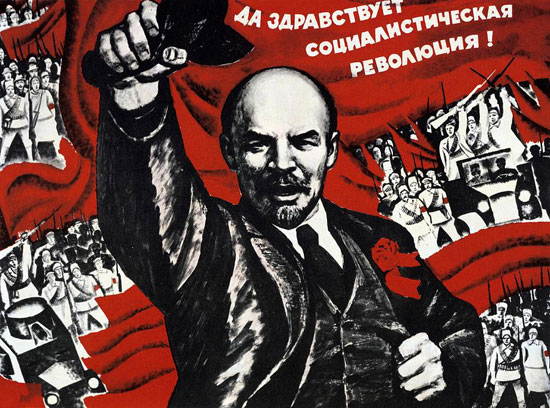

Lenin brought communism into the 20th century. Leader of the Bolshevik Party and the Russian proletariat, inspiration of the first-ever successful socialist revolution in October 1917 and of the Communist International, Lenin’s contribution to the cause of the working class and oppressed is immense. But, ANDY HIGGINBOTTOM argues, social democratic ideologues are determined to destroy every vestige of Leninist influence.

Last year a stream of ‘Marxists’ were elevated to near celebrity status in bourgeois media. Their brief was not praise Lenin, but to bury him:

‘Lenin, the man, died in 1924. But Lenin, the icon of Soviet power, is meeting its end today . . . Thanks to the revolutions of Eastern Europe, time has run out for Lenin.’ (Orlando Figes, The Guardian 30 April 1990)

It is not enough for the imperialist powers that socialism has collapsed in Eastern Europe. Imperialism seeks eradicate the very idea that socialism is possible. In fact it is the opponents of revolution who reduce Lenin to an icon rather than address the substance of his ideas. Why? Because of their potency and relevance. Lenin’s political thought culminates in his analysis of imperialism and the necessity of an actual struggle for socialism.

Imperialism and the split in socialism

In 1916 Lenin showed that the concentration of production in the hands of a few massive capitalist associations, fusion of banking with industrial capital, the export of capital to set up production with cheap labour in the oppressed nations, and competition between the major capitalist nations to grab each other’s colonial possessions were features which together defined a qualitatively new era. Imperialism, Lenin argued, was both the highest and the last stage of capitalism. (CW, Vol 22, p266).

With the onset of world-wide imperialism what had been a specific feature of England’s colonial monopoly in the nineteenth century, the exploitation of oppressed nations and creation of a labour aristocracy which ‘lives partly at the expense of hundreds of millions’ in the opressed nations, becomes the central issue for all political class struggle. (CW, Vol 23, p107). Lenin re-established the communist tradition founded on Marx and Engels’ fight against opportunism in the English labour movement.

For Lenin, imperialism was not only a matter of economics. He sought in economics the material basis of and explanation for the shocking betrayal in 1914, when nine-tenths of the leaders of the Second International supported their own ‘fatherland’ in killing workers from other countries.

‘Opportunism means sacrificing the fundamental interests of the masses to the temporary interests of an insignificant minority of the workers . . . an alliance between a section of the workers and the boureoisie … Opportunism was engendered in the course of decades by the special features in the period of development of capitalism, when the comparatively peaceful and cultured life of a stratum of working men ‘bourgeoisified’ them, gave them crumbs from the table of their national capitalists, and isolated them from the suffering, misery and revolutionary temper of the impoverished and ruined masses.’ (CW, Vol 21, pp242-3)

Lenin saw the need to break the working class from the influence of opportunism represented by two political trends which appeared inevitably in the imperialist countries. The first trend of bourgeois labour parties rejected the class struggle, promoted national chauvinism and openly collaborated with their own governments. The second trend of opportunism was represented by Karl Kautsky, the leading theoretician of the Second International. Kautsky, while continuing to use the language of Marxism, opposed the war in words but accepted it in deeds. The epitome of Kautsky’s opportunism was his refusal to take advantage of the crisis, seize the initiative and turn the imperialist war into a civil war.

The workers’ revolution of October 1917 would not have been possible without the prolonged struggle by Lenin to defeat these opportunist trends internationally and in Russia. This was Lenin’s own assessment:

‘One of the principle reasons why Bolshevism was able to achieve victory in 1917-20 was that, since the end of 1914, it has been ruthlessly exposing the baseness and vileness of social-chauvinism and “Kautskyism” (to which … the views of the Fabians and the leaders of the Independent Labour Party in Britain … correspond), the masses later becoming more and more convinced, from their own experience, of the correctness of the Bolshevik views.’ (CW, Vol 31, p29)

For Lenin the masses had to be brought into politics, and their ‘revolutionary temper’ realised as the decisive factor. Early in 1917 the Russian proletarians rediscovered their own invention, the Soviets, councils of action embracing the masses of workers, soldiers and peasantry. From April onwards Lenin argued for all power to the Soviets, for an insurrection, for the dictatorship of the proletariat, for socialist revolution.

Not surprisingly it was Kautsky who immediately after the Russian revolution became the ‘principal theoretical antagonist of Bolshevism’. He played a counter-revolutionary role in stopping the German proletariat ‘from following the revolutionary road opened up by the Russian working class’.

The split in the socialist movement between communism and social democracy was irrevocable. The Russian Bolsheviks formed the Third Communist International. Lenin told delegates at its first major congress that an essential condition of the Bolsheviks’ revolutionary success had been ‘the most rigorous and truly iron discipline in our Party’ , and urged the formation of like parties as the most conscious political expression of the proletariat. (CW, Vol 31, pp23-26).

The Communist Party in Britain was thus ostensibly conceived in order to fight imperialism and combat opportunism in the working class. It has since turned into the opposite, and become an agent of a latter day, pro-imperialist Kautskyism.

End of the road for the British Communist Party

The retreat of socialism in 1989/90 has pushed Communist Parties across the world onto the defensive. British CP leader Chris Myant does not attempt to defend socialism. He seizes on the problems of the socialist countries to disavow the communist tradition:

‘The time has come when it is now possible for communists to face a very difficult truth. October 1917, the world event which separates communists from others on the left, was a mistake of truly historic proportions.

Its consequences have been severe. They have characterised and moulded the great traumas of the 20th century: a second world war; Hitler’s gas chambers; Stalin’s gulag; the world of the show trials; the perpetuation of third world fascist dictatorships; the unprecedented, almost unbelievable waste of the arms race in a world of poverty and starvation; the destruction of the Vietnam war … ‘ (Seven Days, 24 February 1990)’

How debased can you get? The Bolsheviks who dared to take power and strove to build a new world have somehow become responsible for imperialism’s crimes against humanity.

Myant tries to set an isolated ‘dictatorial’ Lenin against the ‘democratic’ mainstream of scientific socialism,

‘When they first wrote the Communist Manifesto in 1848 Marx and Engels were thinking of a sudden dramatic break between capitalism and the future society of socialism, of a revolution in which the institutions of the old ‘ order were ‘smashed’ . . . At the end of his life Engels rejected his 1848 analysis . . . It was against the ideas of building upon so-called bourgeois democracy, ideas that flowed from Engels’ rejection of the concept of “overthrow”, that Lenin spent virtually all his life polemicising’

Marx and Engels did change their position on the state, but it was in the opposite direction to that which Myant claims. Lenin’s The State and Revolution, published in August 1917 in order to, ‘re-establish what Marx really taught on the subject of the state’, explains with exceptional clarity what Marx and Engels learnt from the European revolutions of 1848-51, and especially from the experience of the Paris Commune, that is after they had written the Communist Manifesto.

The dictatorship of the proletariat

In 1871 French workers ‘stormed the gates of heaven’. For two months Paris was under elective workers control, then the bourgeoisie regained the upper hand and drowned the first workers revolution in blood. In their 1872 Preface to the Manifesto Marx and Engels stressed that the its programme of revolutionary measures ‘has in some details become antiquated’, and that:

‘One thing especially was proved by the Commune, viz., that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made State machinery, and wield it for its own purposes” ‘. (CW, Vol 25, p385).

It was Marx and Engels who increasingly emphasised that the capitalist state would have to be ‘smashed’. The capitalist class is the ruling class by virtue of its control of the repressive, administrative state apparatus. The state is never neutral, always it is a class power. Capital will not voluntarily give up state power, on the contrary it will use ‘special bodies of armed men, prisons etc.’ to enforce its rule.

The working class cannot simply ‘lay hold’ of this apparatus to defend its social and economic interests as a class. It must make a political revolution to abolish the capitalist state. Engels’ later historical analyses became ‘a veritable panegyric on violent revolution’.

The dictatorship of the proletariat summarises a new type of state, not just a change of government. Whatever the form of government – monarchy, parliamentary democracy, fascist dictatorship – the capitalist state must be overthrown.

The Communist Party is therefore essential. It must direct the most conscious section of the working class, its vanguard which leads the masses in a revolution for state power.

Lenin addressed the socio-economic basis of the withering ‘away of the state under the proletarian dictatorship. Communist society is organised around production for need, not for profit. The transition to communism is only possible after the working class has political power.

Those revisionists of Marxism, like Kautsky in Lenin’s time and Myant today, who reject the dictatorship of the proletariat, not only vulgarise the teachings of Marx and Engels, they reject even the possibility of ever achieving communism.

For Lenin, for creative Marxism

By the turn of this century capitalism encompassed the globe. Its potential appeared to be limitless. The better off Western European workers were being drawn into government. It seemed that the working class majority could be transformed into a parliamentary majority which would harness social production for the common good. The Fabians in Britain and Edward Bernstein in Germany argued that Marxism was old fashioned, confined to the growing pains of capitalism in the nineteenth century. They even adopted a ‘socialist colonial policy’ .

Then the storm broke. The horrors of the First World War brought home to European workers what the peoples colonised by imperialist expansion had never been allowed to forget, the bloody barbarism of the capitalist system.

In this last decade of the twentieth century we are reliving the themes with which it began. Marxism has come under attack for similar reasons, apparent stability provided by another ‘New World Order’. Myant finds much to commend in the ‘advanced industrial states’, and ‘the richness and depth of the civil society and political plurality that has grown up in these societies’. This Eurocentric, and ultimately racist, celebration of the vitality of bourgeois democracy is only possible for someone who has enjoyed the benefits of a welfare state while the rest of the world is starving. Myant, like Kautsky and Bernstein before him, spoke too soon. Imperialism has once again plunged the world into crisis and war.

Lenin’s great political courage in transforming the carnage of war into the first socialist revolution charted the way forward for his generation and ours. The Soviet revolution forged a bridgehead of hope into the future.

Marx and Engels understood that in creating the working class, capitalism creates the force that will become its own gravedigger. Lenin applied this insight to modern conditions. Imperialism has created its own gravediggers in the thousands of millions in the oppressed nations.

The proletarian dictatorship must inevitably assume different forms. Lenin pointed to this potential diversity in his prophetic Our Revolution: ‘Our European philistines never even dream that the subsequent revolutions in Oriental countries, which possess much vaster populations and a much vaster diversity of social conditions, will undoubtedly display even greater distinctions than the Russian revolution.’ (CW, Vol 33, p480).

The shift in the locus of communism to oppressed nations is no accident of history, but a consequence of resistance movements which put revolutionary theories to the test of practice.

The fundamental division of the world between oppressor and oppressed nations is mirrored by the division of socialism within the working class of the oppressor nations. The conclusion of the Leninist analysis is the imperative necessity for communists to combat the pro-imperialist trends in the working class. Workers in the oppressor nations must support the oppressed in order to weaken their common enemy and bring about the socialist revolution. Leninist anti-imperialism is the starting point for the formation of a Communist Party in Britain today.

Workers and Oppressed Peoples of all Countries Unite to Destroy Imperialism!