Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No. 64 – 15 November-15 December 1986

The People’s Republic of Mozambique was declared on 25 June 1975. Born out of ten years of FRELIMO’s guerilla war it was the first expression of people’s power in Southern Africa. The new republic’s President, Comrade Samora Machel, was just 41 years old.

Portugal first invaded the country four centuries before in pursuit of its slave trade — over 2 million Mozambicans were abducted. By the mid-20th century the colony had been turned into an engine for the exploitation of surplus labour. In the south, adult men were shipped to the British-owned mines in Rhodesia and the Transvaal — between 1900 and 1920 alone more than 63,000 died. The mine owners paid a portion of the wages in gold direct to Portugal: it was the colony’s main source of income.

Portugal practised ruthless social discrimination to provide a buffer of privilege for the settlers. 95% of the population was kept illiterate. Eighty-five per cent lived in the countryside and there was little industrial development. The administrators, managers and the few skilled workers were Portuguese.

The colonial regime’s suppression of all democratic rights was demonstrated in 1960 when the army massacred 600 unarmed peasants. The Mueda massacre was Mozambique’s Sharpeville; it marked the turning point for the opponents of foreign rule.

FRELIMO

Dr Eduardo Mondlane united three exile groups and formed the Mozambique Liberation Front, FRELIMO, in Tanzania in 1962. Those wedded to constitutional methods departed when Mondlane began serious preparations for a military struggle.

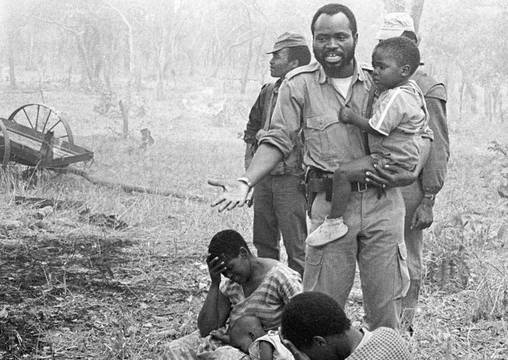

Samora Machel had trained as a nurse. He left Mozambique, joined FRELIMO in Tanzania and volunteered for military training. Machel was soon in charge of training the volunteers. The first armed engagement was on 25 June 1964. FRELIMO established liberated areas in the northern provinces adjoining Tanzania.

A major schism opened up within the Front which paralysed its leadership between 1967-69. On one side were those who had gained control of the liberated zones, only to continue with the old forms of exploitation of the peasantry. They opposed the formation of units of women freedom fighters; fostered tribalism and regionalism; and encouraged anti-white sentiment to cover their own aspiration to become a new class of black exploiters. This embryonic bourgeois nationalist wing was trying to hold back the movement for its own selfish ends. On the other side Samara Machel and Marcelino dos Santos led the revolutionary caucus in FRELIMO asserting that people’s power must be built in the liberated areas. For the revolutionaries the enemy was the colonial system and its agents. The war could not be won unless it was conducted as a people’s war of liberation with the support of the masses. Eduardo Mondlane sided decisively with the revolutionaries, but he paid a heavy price. On 3 February 1969 Mondlane was murdered by a parcel bomb sent by colonial agents.

By 1970 FRELIMO emerged from its internal crisis with a clear ideology and strengthened leadership. Samora Machel was elected President. FRELIMO opened a new offensive in Tete province, the route to the south. Its starting point was the political mobilisation of the local population. FRELIMO introduced for the first time ever health care, education and popular democratic structures. Within two years FRELIMO was able to offer facilities to the Zimbabwean liberation movements, who had been bottled up in Zambia. Tete became the corridor for ZANU to infiltrate its freedom fighters into north eastern Rhodesia.

Portugal was enmeshed in similar protracted wars in Angola and Guinea Bissau. The combined impact of these wars sapped the morale of the Portuguese conscript army. Opposition to fascist-colonial rule broke into open rebellion in Portugal on 25 April 1974 when the democratic Armed Forces Movement deposed dictator Caetano. The freedom fighters in the African colonies had forced a crisis on Portugal’s ruling class and provided an opening for the advance of the Portuguese working class.

The colonial administration in Mozambique crumbled. A transitional government was formed with Joaquim Chissano as Prime Minister. 90 per cent of the settlers fled, but not before they had systematically wrecked all machinery and farm implements. The commercial distribution system collapsed as the shopkeepers went too. But no sabotage could dampen the jubilation: FRELIMO had led Mozambique to independence!

PEOPLE’S POWER— THE FIRST 5 YEARS

FRELIMO immediately set about rehabilitating Mozambique from the ravages of colonial rule. In the first year there were only 80 doctors to serve a population of 12 million and skilled workers and technicians were scarce. FRELIMO implemented measures of immediate benefit to the peasantry and working class. It nationalised schools, the health service, legal practice and rented property. FRELIMO implemented UN sanctions and halted all trade with the racist Rhodesian regime. Smith’s forces waged a campaign of raids and massacres of Zimbabweans and Mozambicans. The monetary cost in 1975-80 of Mozambique’s solidarity with the Zimbabwean people is conservatively estimated at US$556 million.

At the 3rd Congress held in 1977, FRELIMO changed itself from a liberation front to the ‘vanguard party of the worker-peasant alliance’. The Congress addressed the problems of the transition to socialism by its emphasis on the fight to transform production. ‘Dynamising groups’ were set up in workplaces, plans made for communal villages and large state farms operating within an overall planned economy.

However, the initial economic indicators were misleading. Income from the migrant miners increased in the years immediately following independence, and revenues from the export of prawns and cashew nuts remained stable. In 1975 and 1976 the balance of trade was in surplus — exports greater than imports — not least because one consequence of the flight of the settlers was a drastic cut in imports. But as production recovered and imports of machinery and specialised raw materials became necessary, Mozambique was hit by the dramatic reduction in the terms of trade inherent in the imperialist world economy. In 1975 five tons of cotton would pay for a lorry, but by 1980 13 tons were needed. From 1978 onwards the balance of trade went into permanent deficit and Mozambique became increasingly dependent on loans and aid to pay for imports. South Africa’s power of economic leverage against the People’s Republic loomed ever larger. Pretoria cut the numbers of miners, the value of its gold payments, and cut to a third the value of its exports through Maputo.

The liberation of Zimbabwe in 1980 once again engendered great enthusiasm. Within a month the nine independent black states in the region formed the Southern African Development Co-ordination Conference (SADCC) with the aim of furthering co-operation to ‘liberate our economies from their dependence on the Republic of South Africa’. Mozambique was the natural trade route for Zimbabwe, Zambia and parts of Zaire. Production increased in 1980-81 as Mozambique recovered from the Rhodesia war. It seemed that at last there was the chance to rebuild. Apartheid South Africa never gave Mozambique that chance.

APARTHEID’S DESTABILISATION 1980-84

PW Botha’s ascendancy in Pretoria signalled a new wave of terror and economic sanctions designed to prevent the emergence of independent front line states. Apartheid’s war cost the front line states over US$10 billion from 1980 to 1985, some 35% of their aggregated Gross National Product. Mozambique was hit hard by the ravages of SADF special units and the counter revolutionary MNR.

Destabilisation has been effective because it compounded the multiplying difficulties imposed on FRELIMO. The internal class struggle did not end with independence. FRELIMO’s leading cadres became immersed in the administration of the state, and political work with the masses through the party had fallen back. Most of the experienced comrades were concentrated in Maputo and the cities, with a corresponding neglect of the countryside. An emphasis on large projects and centralised control accelerated this process of detachment. Despite FRELIMO’s exacting leadership code of sacrifice, elements who were already privileged in colonial society attached themselves to the state apparatus.

FRELIMO operated subsidies on basic foodstuffs, but the gaping hole in the distribution of goods had not been satisfactorily filled. A ‘black market’ economy was thriving with an aspiring commercial bourgeoisie thwarting FRELIMO’s plans for redistributing wealth to the workers and peasants. Production was slashed by the MNR’s disruption. Exports fell by 60 per cent between 1981 and 1984. Industrial output fell by 13.6 per cent in 1982 alone.

A series of natural disasters compounded the problems. The Zambesi, Limpopo and Incomati rivers flooded in 1977 and 1978. In 1979 Cyclone Justine hit the north. In 1981-83 drought hit Gaza, Inhambane and Tete provinces. FRELIMO had run a successful relief operation in 1979-80, but now food aid had become a weapon against them. In January 1983 Maputo issued an appeal for emergency food aid. The pledges from the capitalist world were reduced, and the MNR were stopping supplies getting through. 100,000 died from this man-made famine.

FRELIMO had sought foreign capital investment, particularly in the light producer and consumer goods sectors, provided that it was on the principle of non-interference and to Mozambique’s benefit. But the Western multinationals followed the lead of their governments in holding back funds. Samora Machel and the FRELIMO leaders did not bury the tensions. He told a mass rally in 1982:

‘After independence when we took off our guns, and exchanged our uniforms for suits and ties, we made a mistake. We looked elegant, but the bourgeoisie had the guns. Now we’re putting our guns on once more, and we won’t make the same mistake this time.’

Matters were brought to a head at the 4th Congress in April 1983. Former combatants and ex-political prisoners were openly critical of the tendency to complacency and even corruption in the state. Out of the Congress came an enlarged Central Committee incorporating many long-serving comrades from the working class and peasantry. A new direction was given to ‘overcome the most basic signs of hunger’, to defeat the MNR and the black marketeers. The Congress also resolved that ‘resources must be allocated with priority to small scale projects which have an immediate effect on people’s living standards’ and which would use local raw materials.

NKOMATI ACCORD AND AFTER

Samora Machel had always avoided the deadly embrace of the International Monetary Fund, having seen it impose austerity measures on Tanzania and Zimbabwe. But interest and repayments on loans contracted in the 1970s fell due. With few exports from the war torn economy to meet the repayments Mozambique’s credit rating collapsed. The Scandinavian countries withheld further loans and aid until an accommodation was made with the imperialist banks. In January 1984 Mozambique was forced to admit that it had default on £145 million debts and entered negotiations to reschedule the £510 million due in 1984-86. Imperialism was turning the screw.

The South African regime used Mozambique’s predicament to force Machel to the negotiating table. The Nkomata Accord — signed in March 1984 — was supposedly a non-aggression pact. Botha trumpeted the Accord as a major foreign policy coup and as the prelude to a series of bogus reforms to quell black resistance within South Africa. Machel was forced to concede that there would be no ANC military presence in Mozambique, but he made no concession on FRELIMO’s political support for the ANC and the liberation of South Africa. In return, Machel secured a public commitment from South Africa to end its aggression and support for the MNR.

In fact the MNR’s atrocities escalated with at first covert and then increasingly open support from the South African military. The MNR had nearly brought Mozambique to its knees and Pretoria had no intention of giving away its advantage. The Nkomati Accord had been exposed as a fraud and Botha’s ‘reform’ programme soon bit the dust when black anger exploded in South Africa in August 1984.

Over the next two years the struggle for the liberation of Southern Africa entered a new and even grimmer phase. Botha responded to black resistance with terror and repression, and the destabilisation of the Frontline States became ever more crucial in order to prevent ANC incursions and support for liberation. Mozambique became, once again, the primary target.

In the last year, with the failure of the Commonwealth to implement sanctions, the frontline states have become the spearhead for effective action against apartheid, outside South Africa itself. Zambia and Zimbabwe were outspoken in their criticism of the failure of Britain and the west to implement sanctions at the Commonwealth mini summit in August 1986. A few weeks later the Non-Aligned Movement Conference held in Harare confirmed that the frontline states would be leading the sanctions movement. The recolonisation of Mozambique is central to Botha’s ability to crush the independence of the frontline states, especially Zimbabwe, and block their support for liberation forces. Samora Machel was nobody’s silent victim. He entered a period of incessant activity to galvanise the frontline states into concerted defence. Zimbabwe and Tanzania increased their commitment to the war against the MNR. The frontline leaders put pressure on Hastings Banda, puppet chief of Malawi, to cease providing facilities to the counter revolutionaries. Samora went out to the people in Mozambique to rally and unite them. For all apartheid’s sophisticated weapons, he used to say, we have the most sophisticated weapon — people’s power.

Samora Machel’s death on 19 October was no accident. It was an historical imperative for imperialism and racism. In the preceding two weeks apartheid Defence Minister Malan issued a stream of threats to Machel’s personal safety. South African commando units and the MNR were increasingly active around Maputo. Days before the air disaster Samora confided that there had already been an assassination attempt:

‘They have already tried. In November 1985 they infiltrated bazookas to Mozambique in an effort to kill me.

‘I’m in their way. I haven’t sold out to anybody and my hands are clean.’

In his life Samora Machel united the people of Mozambique and led them to independence. The circumstances of his death have united the oppressed throughout Southern Africa in their determination to destroy the system of apartheid oppression.

Viva FRELIMO!

Andy Higginbottom

BROTHER FROM THE WEST

Brother from the West —

(How can we explain that you are our brother?)

the world does not end at the threshold of your house

nor at the stream which marks the border of your country

nor in the sea

in whose vastness you sometimes think

that you have discovered the meaning of the infinite.

Beyond your threshold, beyond the sea

the great struggle continues.

Men with warm eyes and hands as hard as the earth

at night embrace their children and depart before the dawn.

Many will not return.

What does it matter?

We are men tired of shackles. For us

freedom is worth more than life.

From you, brother, we expect

and to you we offer

not the hand of charity

which misleads and humiliates

but the hand of comradeship

committed, conscious,

How can you refuse, brother from the West?

FRELIMO, 1973