Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 105 February / March 1992

Street fighting years

Out of the Ghetto: my youth in the East End: Communism and Fascism 1913-1939 Joe Jacobs, Phoenix Press, 2nd edition, 1991, 320pp

This is the second edition of Joe Jacobs’ book – it was first published in 1978, a year after his death. He died while writing it and the text was completed from his documents by his daughter. Jacobs was born in 1913 in the East End of London, the son of Polish and Russian Jewish immigrants. His book is a historical document – he believed that by a meticulous presentation of all the facts, his readers would draw their own political conclusions. In some ways this makes for tedium. There are long lists of names, documented daytrips to the seaside, endless family connections, with few clues about the significance of all this.

Yet out of a wealth of facts, there gradually emerges a picture of life in the East End between the Wars: grim lives of relentless poverty and exploitation in the clothing industry; rackrenting landlords and greedy sweatshop owners. Alongside this a life on the streets and in cafes reflecting the Jewish culture of the area. It was also a political street life as the youth, at most one generation from Soviet Russia, hotly debated world affairs. Street meetings were a commonplace – Christians, Labour Party, Trade Unions, Communists, Socialists, Anarchists, Unemployed Workers and many others (including an ex-police inspector who claimed to be the Heir to the Throne of England).

What also emerges is a picture of the young Communist, Joe Jacobs, an activist, not a theoretician or intellectual, boorish as young men can be, but also self-critical and shy with girls, who by the age of 23 was Stepney Communist Party branch secretary and a leading figure in the fight against fascism. Not that you would know this from official Communist Party histories. Joe Jacobs and his friends were written out of history.

To understand the politics responsible for hounding Jacobs out of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and out of their history, it is necessary to look beyond his own memoirs. Jacobs doesn’t attempt to explain his opponents’ position in detail. Phil Piratin, a Stepney Communist from 1934 onwards, and later a Communist MP, writes his own account in Our Flag Stays Red (1948):

‘The Stepney Communist Party was enthusiastic and hard working on issues that were clear, such as anti-fascism and unemployment. Complex issues, or those calling for balanced presentation, were often over-simplified and sometimes avoided. Activity was undertaken almost solely by the directive of higher organisations of the Party, rarely from local initiative, and hardly ever arising from the needs of the people.’ (p14 my emphasis)

If Jacobs’ book needs a justification for being written, the exposure of this sly, misleading paragraph will serve the purpose on its own. The ‘balanced presentation’ which Piratin’s superiority requires was to become, in Jacobs’ view, an accommodation with Mosley’s fascism, but above all with the Labour Party.

Jacobs’ first doubts about the direction of the CPGB came with the closing down of International Labour Defence (ILD) in 1935 on the grounds that the CP should concentrate on Party building and united action with the Labour Party and trade unions. Jacobs saw the ILD, and other mass organisations which were soon to be closed down, as recruiting and mobilising grounds for the CP – a means of involving people in activity which would lead them to communism. He was shaken by the decision but nonetheless accepted it after a long argument. The emergency of Mosley’s British Union of Fascism (BUF) in the East End was to focus his attention.

It was around this time that arguments emerged in Stepney CP from a section of its leading members (with a direct link to District and National leadership) that members should give up ‘street work’ in favour of ‘Trade Union work’. Jacobs rejected the view that greater influence in the Labour Party and trade unions would be more effective in fighting fascism than anti-fascist work on the streets. The unions, he argued, were in the hands of right-wing leaders and ‘the Social Democrats’ role in society was to betray the workers’ – and what about the masses of unemployed and unorganised workers?

‘Always, and as the years passed on, more and more, the positions these people captured in the unions were held to be more important and sacred than the outcome of this or that particular struggle.’ (p193)

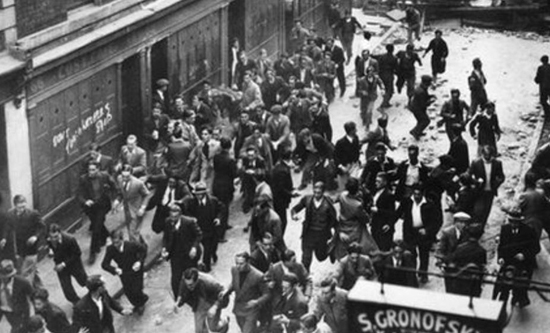

The watershed of the dispute came when Mosley announced that his blackshirts would march through the East End on 4 October 1936. It was a deliberate anti-Jewish provocation. Jacobs and his friends knew that the fascists could be sure of massive police protection. This was not the first battle with the blackshirts: many had waged an unremitting fight to prevent fascist meetings and marches. Arrests and injuries were commonplace; it was the stuff of Jacobs’ everyday life. As soon as Mosley’s march was announced in the East End anti-fascists began to organise to stop them, adopting the slogan ‘They shall not pass’ from the Spanish anti-fascist movement.

Jacobs and his circle were shocked when the CP called for support for a YCL rally in Trafalgar Square in support of Spanish workers at the same time as the fascist march. They already knew that the District leadership were opposed to confronting the fascist and this was confirmation that this was the Party Line. Jacobs was instructed by the local full-time organiser: ‘If Mosley decides to march let him’. This was also the Labour Party position – ‘free speech’.

Jacobs and his friends decided to fight the decision and a meeting with the District leadership was arranged, only days before the march. While they were being treated to a diatribe on the comparative importance of the YCL rally, a message arrived from central headquarters that the decision had changed. The leadership had become ‘aware of the real situation only that day’. The ‘real situation’ was that with or without the CP, the East End would march against the fascists.

At first Jacobs thought this a great victory – Cable Street went down in history as the day the fascists were beaten. But after the march, the District leadership renewed its attack on ‘street work’, publishing a document proposing emphasis on work in the trade unions, the Labour Party and the Co-op Guilds, and omitting confrontation with the fascists.

What was at issue was not the distinction between ‘street work’ and ‘Trade Union work’ but the accommodation to Social Democracy that underlay the turn. Jacobs knew this and was blunt in his opposition. For his pains, and still considering himself a loyal Communist, Jacobs was first suspended and then expelled from the CP with little chance to argue his standpoint. One must conclude that if the CPGB could find no room for the likes of Jacobs, then it had no right to call itself Communist.

It is hard in a short space to do justice to Jacobs’ book which contains a wealth of facts and description of political struggle: the planned escape of a Yugoslav Communist by the ILD network; his friends who fought in the Spanish Civil War. It is timely, now that fascism is on the upsurge again, that Jacobs’ account is once again available to political activists and Communists. In this way his political struggle as a Communist continues. Which is more than can be said for the CPGB who have ended, as Jacobs predicted, in the ranks of Social Democracy, ready to betray the workers’ struggle.

Carol Brickley