On 6 October 1985, the Broadwater Farm Estate in Tottenham erupted. The uprising against the police was in response to the death of Cynthia Jarrett the day before, a black mother who collapsed and died of a heart attack after the police violently raided her home. The community rose in anger, solidarity and defiance. The uprising, dismissed by the media as ‘mindless violence’, was in fact a spontaneous collective response to years of police harassment. Youth took to the front line with petrol bombs, supported by the wider community, and Broadwater Farm became a stronghold of resistance against police racism. In the years that followed, the state sought revenge, framing Winston Silcott, Engin Raghip and Mark Braithwaite – the Tottenham Three – for the death of PC Keith Blakelock. Their wrongful convictions and eventual exoneration would become emblematic of the racist British justice system. Forty years later, the Broadwater Farm uprising remains a key moment in Britain’s anti-racist struggle, when black and working-class youth showed, as ever, that self-defence is no offence.

Systemic racism and the road to Broadwater Farm

The Broadwater Farm estate had long been a target of state repression. Built in the 1970s, it was home to a large black working-class community, subject to systemic racism in housing, education and employment. By the early 1980s, police harassment was routine, with stop and search under the ‘sus’ laws targeting black youth. The state viewed Broadwater Farm as a place to be ‘contained’ and policed like a colonial outpost, rather than a community.

In the summer of 1981, uprisings in Brixton, Toxteth, Moss Side and across England shook the establishment. These uprisings, led by black youth and their white working-class allies, were responses to police brutality and mass unemployment. They taught communities vital lessons about self-defence, solidaity, and resistance. Broadwater Farm residents carried those lessons forward. By 1985, the estate had a tradition of community organisation through the Broadwater Farm Youth Association, which mobilised residents in local campaigns and meetings, building a culture of collective responsibility and resistance.

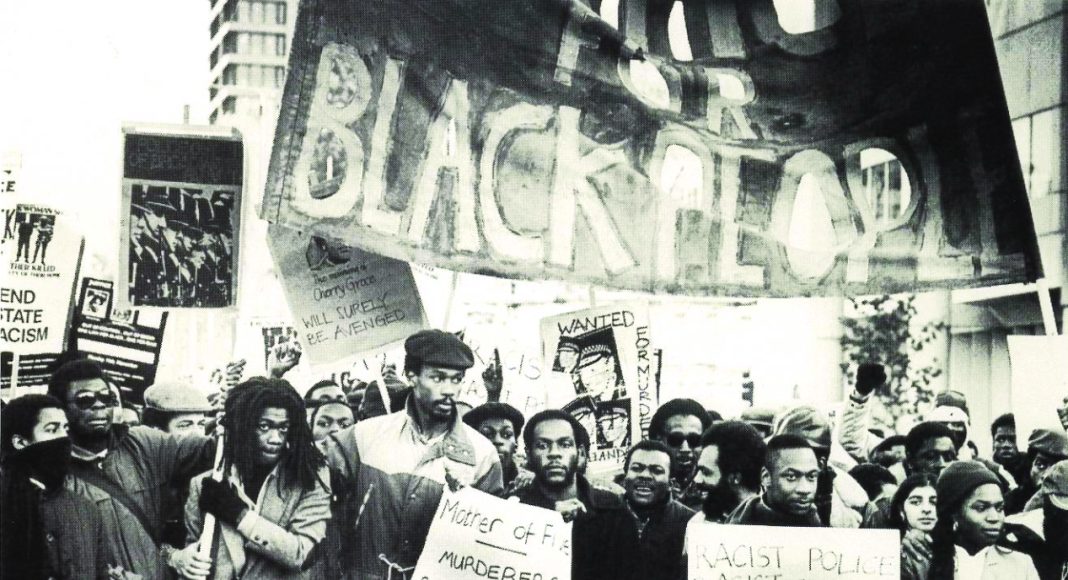

In late September 1985, police in Brixton shot and paralysed Cherry Groce during a raid on her home, sparking days of uprising. A week later, the same horror struck Tottenham: Cynthia Jarrett collapsed and died of a heart attack after police raided her home on the false claim that her son’s car was a stolen vehicle. At the inquest, the coroner ruled that her death was ‘no accident’, but this information was buried as the media narrative vilified the community.

The uprising: collective resistance

On 6 October 1985, hundreds of residents marched to Tottenham police station demanding justice for Cynthia Jarrett. Throughout the rest of the day the community clashed with riot police, confronting them with barricades and petrol bombs. The police were pushed back, and they panicked, with some dropping their riot shields and fleeing. For the first time in Britain, police officers armed with plastic bullets were deployed (although plastic bullets were never fired), and by the end of the night, one police officer, PC Keith Blakelock, was killed; he was the third police officer killed in a riot since 1833. The state used his death to justify years of mass arrests, demonisation and a siege of the estate.

Siege, surveillance, and collective punishment

After the uprising, there was a campaign of collective punishment. Six weeks later, the police were still raiding two homes a week, often without warrants. The police smashed down doors with pickaxes and seized food, clothing, baby milk, jewellery, photographs and passports. Families were left destitute, forced to turn to the council for basic survival. Children were interrogated in schools and threatened with imprisonment for associating with certain friends. Social services were used as a weapon, with parents warned that their children could be taken into care if they did not comply. The goal was terror and compliance.

The estate became a militarised zone, with 200-400 police stationed in vans, helicopters overhead, phone lines tapped and gun units patrolling. In a letter submitted to FRFI 53 in October/November 1985 from HMP Brixton, Winston Silcott referred to Broadwater Farm as ‘like Northern Ireland, now under siege by these pole-lice.’ The police aimed to extract confessions at any cost. Interrogations lasted for days; detainees were deprived of food, clothing, and sleep; solicitors were denied access or replaced by lawyers appointed by the police. Youth as young as 13 were charged with murder to coerce testimony – their cases would later collapse in court. Those with even minor records were branded ‘known criminals.’ The aim was clear: criminalise the whole community, divide families and destroy resistance.

Media hysteria: the state’s propaganda arm

The ruling class needed to isolate Broadwater Farm and the media played its usual role as the state’s mouthpiece. Headlines referred to so-called ‘Moscow-trained hit squads’ and ‘hyenas hacking Blakelock to death’, while the killings of Cherry Groce and Cynthia Jarrett were dismissed as ‘tragic accidents.’ The Daily Telegraph illegally published the name and charge of a child, while The Mail on Sunday branded Dolly Kiffin, a respected community leader, as the ‘Godmother of Broadwater Farm’, likening her to a corrupt gangster. This campaign of demonisation aimed to turn public opinion against the community and justify the police siege.

This media hysteria was paired with the violent siege strategy. It was directed by Metropolitan Police Commissioner Kenneth Newman, who had previously served in the north of Ireland from 1973 to 1979, where he had reorganised the Royal Ulster Constabulary into a ruthless intelligence gathering force, notorious for torture and murder of Irish republicans. These tactics were imported by Newman to London in 1981 and deployed on Broadwater Farm in 1985.

The defence campaign: community strikes back

Despite the terror, Broadwater Farm fought back. Within days, the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign (BFDC) was established, continuing the estate’s tradition of collective organisation through the Broadwater Farm Youth Association. The campaign organised open committees on publicity, legal defence and fundraising. It demanded:

- An independent inquiry into the death of Cynthia Jarrett.

- A full investigation into DC Randall, an officer notorious for terrorising black people on the estate, and the actions of Tottenham police.

- An end to police harassment of black youth.

- A proper defence of all those arrested.

Collective organising was central to the defence campaign, mobilising residents and anti-racists to confront state repression. FRFI played an active role in the campaign, distributing leaflets, picketing courts and council meetings, and insisting that only collective defence could resist organised state oppression. The campaign developed confidence and solidarity on the estate, turning outrage into action and exposing the police and media lies. This democratic approach enabled the campaign to launch strike action and organise pickets that directly challenged the authorities. However, because it was independent, militant, and committed to anti-racist unity, the campaign was boycotted by the established labour movement, which feared the rise of a grassroots force outside its control and sought to limit its influence.

The solidarity displayed through the BFDC forced the state to double down on its terror. In February and March 1986, arrests surged again. FRFI reported that one witness recalled hearing a police officer say, ‘we’re not leaving the Farm until we kill one of these black bastards.’ Families were terrorised in their homes; youth were dragged from their beds, beaten, and detained for months. Teachers and pupils were fingerprinted on police orders. Defendants were threatened with consequences if they contacted the Defence Committee. Employers warned workers they would lose wages if they attended meetings. The aim was to break solidarity.

The people of Broadwater Farm refused to be intimidated. Through collective courage and unwavering unity, the estate’s residents, with the support of anti-racist allies, showed that organised, grassroots action could organise a powerful fightback.

The Tottenham Three

While numerous people who rose up would be arrested and sentenced to long prison terms, the most infamous miscarriage of justice was the case of Winston Silcott, Engin Raghip, and Mark Braithwaite, the Tottenham Three. Convicted for the murder of PC Blakelock in 1987, they became symbols of the state’s determination to find scapegoats at any cost, to punish hostages from the community in order to intimidate it. Silcott, already targeted for his outspoken criticism of police harassment, was demonised in the press before his trial began. The police tampered with evidence, fabricated confessions, and silenced witnesses. The Tottenham Three were condemned in a blaze of racist headlines. Their trial was less a search for truth than a political showpiece designed to demonise the community.

A mass campaign was built for their release, supported by the BFDC, FRFI, local community organisations and other anti-racist groups across Britain. They organised marches, strikes and public meetings, and produced counter-investigations that exposed the police’s lies. Residents of Tottenham raised funds and travelled across Britain to speak at rallies, ensuring the case could not be buried.

The Tottenham Three had their convictions overturned in 1991. This victory was won through community solidarity and support from allies, showing that united action can challenge state repression. But the case left deep scars: the Tottenham Three had spent years behind bars for a crime they did not commit, and the police officers who fabricated evidence faced no real consequences. The case of the Tottenham Three stands as one of the clearest examples of Britain’s racist justice system in action, a system willing to sacrifice innocent lives to protect its own authority and to crush the spirit of a community that dared to fight back.

Labour Party betrayal

Throughout, the Labour Party proved itself no ally. Roy Hattersley, Labour’s deputy leader, condemned the uprisings as ‘lawlessness’. In February 1986, then leader of the Labour Party Neil Kinnock staged a cynical visit to Broadwater Farm, where he refused to denounce the police’s siege on the estate. Just hours after Kinnock’s visit, police raided and arrested the very residents who had hosted him. When black communities fought back, Labour sided with the police, echoing Thatcher’s slanders. As FRFI warned at the time, the Labour Party represents not the oppressed but the privileged layer of the working class, desperate for stability, even if it means supporting repression. This betrayal remains relevant today, as Labour continues to support policing and state measures that disproportionately target black and working-class communities.

Legacy and lessons

Only organised community defence can resist state violence. The police will not protect us; they are the armed wing of the racist British state. The media will not tell the truth; they are propaganda machines for capital and imperialism. The Labour Party will not stand with the oppressed; it will always denounce the working class when they rise up. In the aftermath of the anti-racist uprisings of the 1980s, the state poured money into different deprived estates to buy off people who could be made into safe ‘community leaders’ while arresting and imprisoning those who fought back. This divided and ultimately pacified the communities who were being criminalised.

As we wrote in FRFI 55 (January 1986), ‘Oppression at this level of state organisation can only be overcome by community organising for its own defence. Police harassment of the black community will not go away if it is not exposed … Every time a community fights back, there is a hope for peace in the future.’ These lessons must be carried forward to the struggles ahead.

The struggle continues!

Self-defence is no offence!

Destinie Sánchez

FRFI 308 October/November 2025