On 3 September 2025, marking the 80th anniversary of the defeat of Imperial Japan and the end of the Second World War, Chang’an Avenue in Beijing thundered to the sound of Chinese troops and military vehicles from the People’s Liberation Army. This was the largest military parade in the history of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) – a warning to the United States and other imperialist powers of the potential cost of a military conflict with China.

A red flag exercise

The parade featured 12,000 troops, underwater drones, stealth fighters, hypersonic rockets, laser weapons and nuclear missiles. Twenty-six heads of state attended, including Vladimir Putin of Russia and Kim Jong Un of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Leaders were present whose countries have been pushed into closer partnership with China because of US sanctions, tariffs and other aggressive actions. This included Jorge Rodriguez, National Assembly President of Venezuela, and President Miguel Diaz Canel of Cuba, but also Narendra Modi of India. Modi is an erstwhile ally of US President Donald Trump. However, in August the Trump administration doubled tariffs on Indian goods entering the US to 50%. Modi’s presence at the parade served as a reminder of the potential might of the ‘global south’. India and China’s combined population is 2.8 billion, 30% of the world total, and with 21% of the world’s GDP.

An EU representative stated that the parade was ‘a direct effort to challenge the rules-based international order by establishing an anti-Western coalition.’ On 9 September, Trump urged the EU to boycott Indian petroleum products (which are derived from Russian crude) and impose high tariffs on China and Russia. On 15 September, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent confirmed that if the EU imposed tariffs of 50-100% on those countries, the US would match the tariffs in an effort to bring Russia’s war in Ukraine to an end. China’s Foreign Ministry warned it would retaliate against such measures: ‘What the US has done is a typical move of unilateralism, bullying and economic coercion.’ Trump seeks to negotiate better trade terms with China; his administration paused a planned sale of $400m of weapons to separatist Taiwan in the meantime.

The growing bellicosity of western imperialism toward China is a reversal of decades of economic integration and accommodation. This changing relationship reflects the balance of class forces in China and globally. It is necessary to revisit the Chinese people’s victorious war against Japan and the class forces which then established the PRC in 1949 to understand subsequent developments.

Revolution by the party of workers

At the time of China’s socialist revolution of 1949, 90% of the Republic of China’s 550 million people were rural peasants, from landless farm labourers to wealthy landlords, in a semi-feudal system of property relations. Alongside this were the ruling capitalist class (encompassing owners of large and medium-sized enterprises, with the bigger capitalists dependent on exporting their products to the imperialist states) and the workers whom they exploited. Marxists have long recognised the contradictions in waging a socialist revolution in a country where capitalism is underdeveloped and therefore where the urban working class (the fundamentally revolutionary class) is numerically small, making an alliance with other classes, especially the poor peasant majority, necessary.

Although historically temporary, the worker-peasant alliance is immortalised in the cultural symbols of the Russian revolution of 1917. In this tradition the Communist Party of China (CPC)’s emblem is a hammer and sickle. China’s national flag, however, has one large star, representing the CPC, leading four smaller stars representing four social classes: workers, peasants, urban petit bourgeoisie and ‘national’ bourgeoisie. According to the CPC’s ideological framework, this alliance was necessary to defeat China’s imperialist oppressors. The elements of this framework were set out by Mao Zedong, CPC chairman and leader of the 1949 socialist revolution.

In 1926 Mao argued within the CPC that in the struggle for socialism in China the main enemies were the big landlords and capitalists who functioned as compradors for the imperialists. The strongest allies of the proletariat were the semi-proletarian landless workers, poor peasants and petit bourgeoisie, while the medium-sized Chinese bourgeoisie were unreliable: ‘As for the vacillating middle bourgeoisie, their right-wing may become our enemy and their left-wing may become our friend but we must be constantly on our guard and not let them create confusion within our ranks.’1 Such Chinese capitalists catered to a narrow domestic market, resenting the backwardness, corruption and bureaucracy of semi-colonised China, their profits constantly under pressure from imperialist monopolies. Many aspired to free Chinese capital from these fetters – and secure a well-fed, educated workforce to exploit, modern infrastructure and consumers to buy their products. They rallied around the republican Kuomintang (KMT) party, which represented nationalism but simultaneously fought a civil war against the communists from 1927.

In the era of imperialism (monopoly capitalism) since the turn of the 20th century, as Lenin recognised, capitalism is no longer progressive but decaying and can only develop imperialistically. What the KMT refused to accept was that only the Chinese masses under communist leadership could break the chains of imperialism and feudalism.

In the 1930s, as Imperial Japan threatened invasion, the USSR and CPC called for an alliance with the KMT and against imperialism; disgruntled nationalist officers kidnapped KMT leader Chiang Kai-Shek and forced him to negotiate a truce with the communists. In 1937 Japan invaded mainland China. The truce held and combined communist-nationalist forces beat back the invaders despite continued betrayals by the KMT which received US backing.

By 1940 Mao placed a stronger emphasis on the idea that Chinese capitalists were potentially revolutionary: ‘China’s national bourgeoisie has a revolutionary quality at certain periods and to a certain degree, because China is a colonial and semi-colonial country which is a victim of aggression. Here, the task of the proletariat is to form a united front with the national bourgeoisie.’2 Mao argued that unlike the Russian Bolsheviks in 1917 the CPC could not build a socialist state immediately, since Russia had been a ‘military-feudal imperialist’ country whereas China was semi-colonised. Mao contended that a ‘New Democracy’ must be built in China’s conditions, neither a dictatorship of the proletariat nor a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, but a joint dictatorship of four classes including capitalists. Only such a state, Mao and his followers argued, could develop the productive forces and revolutionise China before socialism could be built in earnest.

Japan surrendered to the allies in 1945, and its occupation of China was broken; civil war then resumed, with US imperialism continuing to arm and fund the KMT. Mao reasserted the role of ‘national’ capitalists: ‘The upper petty bourgeoisie and middle bourgeoisie, oppressed and injured by the landlords and big bourgeoisie and their state power, may take part in the new-democratic revolution or stay neutral… They have no ties, or comparatively few, with imperialism and are the genuine national bourgeoisie. Wherever the state power of New Democracy extends, it must firmly and unhesitatingly protect them’.3

The revolutionary movement led by the CPC overthrew the capitalist Republic of China in 1949 and on 1 October established the People’s Republic. The KMT fled to exile in Taiwan, bringing with them much of the Chinese big bourgeoisie. Some Chinese capitalists, disillusioned with the KMT due to its corruption and disastrous currency reforms, stayed in Shanghai under communist rule or relocated their families to Hong Kong (then a British colony). The PRC’s head of government Zhou Enlai encouraged such capitalists to return or remain in Shanghai with assurances that, although heavy industry would remain in state hands, smaller private interests would be protected, and capitalists would be offered a leadership role in the Chinese state. One such industrialist, Liu Hongsheng, convinced fellow bourgeoisie to cooperate with the CPC, arguing that ‘we must eat bitterness at first so that we can enjoy happiness later.’4

Mao argued that if China’s weak capitalist class was to play a role in revolutionising China, this was only with the cooperation of the Chinese working class led by the CPC and the assistance of the international proletariat, led by the Soviet Union: ‘As things are today, it is perfectly clear that unless there is the policy of alliance with Russia, with the land of socialism, there will inevitably be a policy of alliance with imperialism, with the imperialist powers.’5 This reality was to determine the course of the Chinese revolution, its evolving relationship to imperialism and its role in the international anti-imperialist struggle.

Revolutionary challenge to imperialism

Hyperinflation had eroded living standards in 1945-49 and almost half the urban population was unemployed. With the establishment of the People’s Republic, the CPC set out to break the chains of imperialism, feudalism, and capitalism. Land reform campaigns, collectivisation, and the push for industrialisation transformed class relations. Much of the urban workforce was employed in state-owned enterprises, guaranteeing their living standards – the so-called ‘iron rice bowl’.

Still, only 14% of the CPC’s membership were urban workers in 1956. China’s alignment with the Soviet Union provided critical assistance in heavy industry and technical training. Throughout the 1950s, the imperialists viewed the People’s Republic of China as a pariah state, refusing diplomatic recognition, imposing embargoes, and supporting the KMT regime in Taiwan as ‘the legitimate government of China’. The example of the Chinese revolution threatened the colonial and semi-colonial system the imperialist bloc had established in Asia.

China’s internationalist support for anti-imperialist movements in this period reflected the early strength and organisation of the proletariat in determining the foreign policy of the PRC. Chinese volunteers fought on the side of the DPRK and Soviet Union in the Korean War (1950–53), directly confronting US-led imperialist troops. In Vietnam in this early period, the PRC provided weapons, training and engineers to aid the communist-led Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the Viet Cong in their struggle against French colonialism.

Class war and class collaboration

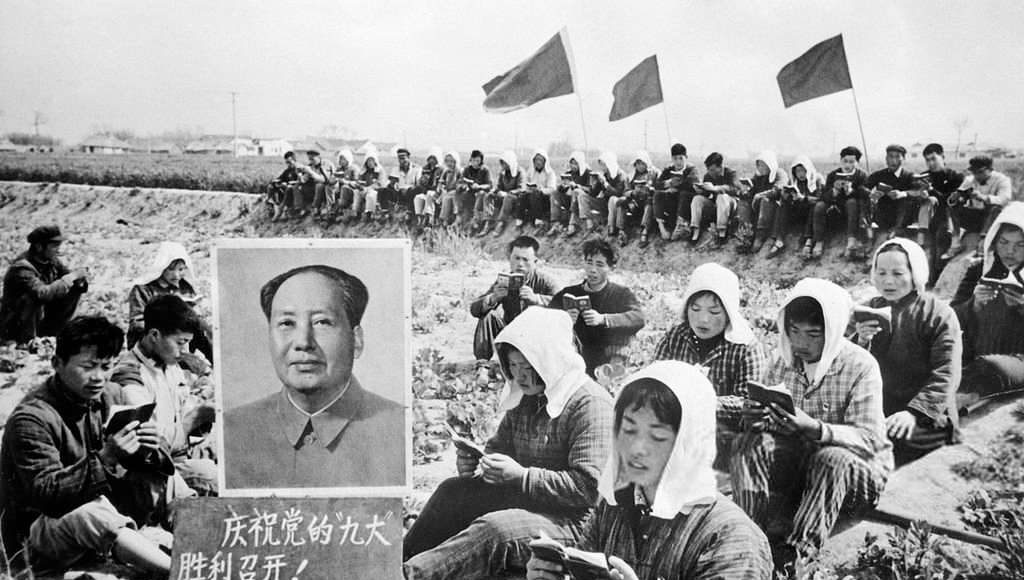

Though he did not abandon the notion of a ‘joint dictatorship’ of four classes, Mao’s base of support was the working class and poor peasants. Mao foresaw the intensification of class struggle as new forces of production developed in China. In the period from the triumph of the revolution in 1949 to Mao’s death in 1976, the CPC was riven with factionalism which after 1966 verged on civil war.

Mao and his allies drove forward the policies which dispossessed capitalists and landlords through The Great Leap Forward (1957-59) and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-76). ‘A process of agricultural collectivisation begun in the 1950s did improve rural education, health, housing, social security and food distribution for the masses… The infant mortality rate measured per 1,000 people fell from 200 in 1949 to 81 in 1956.’6 In 1950 the CPC abolished arranged marriage. ‘Nurseries, kindergartens, public canteens and homes for the elderly helped reduce the burdens of domestic work on women. By 1960 the number of women college and university students had risen five-fold in a decade.’7

Mao struggled against bourgeois tendencies in the party which sought to redirect the means of production from collective social development toward private capital accumulation – ‘those Party persons in power taking the capitalist road’ – led by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. The eventual outcome of this class struggle can only be understood as part of the general failure of the communist movement internationally. The failure of the working-class movements in the imperialist countries, led by the likes of Britain’s Labour Party (which conceived the establishment of NATO) and the opportunist trend which supported it, isolated the socialist bloc and provided material and ideological support for counter-revolution. Imperialism exploited the weakness of the international communist movement to pit the PRC and the USSR against each other.

Will Jones

Continued in part II

1. ‘Analysis of the classes in Chinese society’, March 1926.

2. ‘On new democracy’, 1940.

3. ‘The present situation and our tasks’, 1947.

4. Sherman Cochran, ‘Capitalists choosing Communist China: The Liu Family of Shanghai, 1948-56’, in Jeremy Brown and Paul Pickowicz (eds) Dilemmas of Victory, Harvard University Press, 2007.

5. ‘On new democracy’, 1940.

6. Trevor Rayne, ‘China: along the capitalist road’, FRFI 188.

7. Ibid.

FRFI 308 October/November 2025