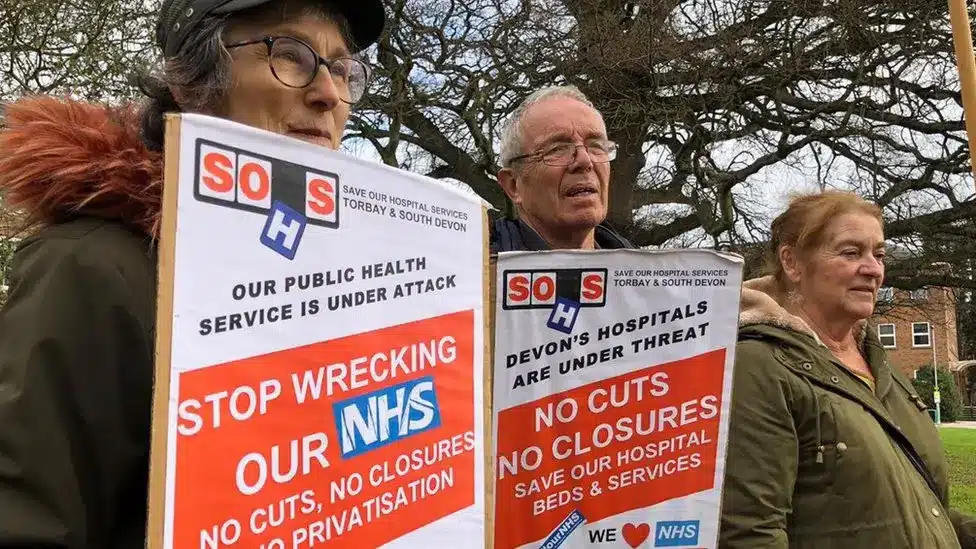

Stand up! Fight back!

The health of the working class has been deteriorating for more than a decade. A study by the Institute of Health Equity at University College London has found that more than a million people lived shorter lives in Britain between 2011 and 2019 (start of the pandemic) than they would have done had they lived in the wealthiest areas. Almost 150,000 of these deaths were attributed to post-2010 austerity measures which have contributed to falling life expectancy and rising health inequalities in Britain. Poorer people are more likely to spend at least a quarter of their lives in ill-health, while 2.6 million people are currently not able to work due to long-term sickness. Between 2022 and 2023, the number of children living in food poverty almost doubled; now over one million children in Britain experience destitution because they cannot be kept adequately fed, clothed, clean or warm and four million children face food insecurity.

Energy poverty is more prevalent; the End Fuel Poverty Coalition says that last winter Britain saw nearly 5,000 excess deaths caused by cold homes. Nearly one in four British households in social housing experienced energy poverty, creating psychological stress, exacerbating long term conditions, increasing respiratory illnesses and aggravating the impact of sickle cell disease.

Health system in crisis

Alongside worsening working class health, the Tory government continues to drive the NHS into the ground. Hospital bed occupancy in England in January 2024 stands at 93.5%, well over the safe occupancy level of 85%. December 2023 figures show that over 150,000 people had 12-hour waits in A&E departments, more than one in nine attendees. The government’s target of 5,000 new beds by winter has not been met – there has only been an increase of 3,294 general and acute care beds. Britain has fewer beds per capita than all but one of the developed OECD countries.

Universal NHS dentistry has almost disappeared in many parts of Britain. Six million fewer courses of NHS dental treatment were provided in 2022-23 than during the previous year and funding in 2021-2022 was more than £500m less in real terms than in 2014-15. One of the most common reasons now for hospital admission in children aged 6-10 years old is tooth decay.

Maternity services are in crisis. Care Quality Commission inspections of 45 maternity services that followed the Ockenden review into the Shropshire maternity scandal, which saw 300 babies left dead or brain damaged by inadequate NHS care, reveals nearly half, 21 in all, were delivering an inadequate service, and overall, two-thirds had insufficient staff. There is a shortage of 2,000 midwives, and staff are having to work 100,000 unpaid hours a week to compensate, according to the Royal College of Midwives.

The government’s target to reduce long waits for treatment by March 2024 will not be met. NHS England shows waiting list numbers fell in November 2023 – but are still higher than they were in January 2023 despite numerous fiddles to exclude patients from the count.

Staffing

There are over 120,000 staff vacancies in the NHS and over 150,000 staff vacancies in social care. England has 7.8 GPs per 10,000 people while the OECD average is 10.8, equivalent to 16,700 GPs. The government has said 6,000 would be recruited by 2024, but there are currently 1,996 fewer fully-qualified full-time GPs than in September 2015. One in seven British-trained doctors will leave to work overseas. 18,000 British-trained doctors are already practising abroad, a 50% increase since 2008, while in 2022, international medical graduates made up 52% of new additions to the NHS workforce.

Government ‘solutions’ to this crisis include pushing down the cost of training, recruiting from abroad, and overtly or covertly encouraging the use of the private sector. Training proposals involve deskilling, for instance, through the introduction of Physician Associates, the development of the new Medical Doctor Degree Apprentices pathway to becoming a doctor and the expansion in the use of health care assistants where nurses are needed. Meanwhile junior doctors are having to strike to restore years of real-term pay cuts.

Labour in the wings

The Labour Party is desperate to show that it will be economically wise and responsible. Wes Streeting, Shadow Health Secretary, at the end of 2023, moaned that the NHS is ‘using every winter crisis and challenge it faces as an excuse to ask for more money’. He made no reference to the real-term cuts in NHS funding since 2010. Labour leader Keir Starmer and Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves have made it clear that no ‘government chequebook’ will save the NHS and major reforms are needed whatever the human cost. Streeting said the NHS will have to get used to money being tight and talked of ‘tough love’ to sort the problems in the NHS, giving managers ‘freedom to innovate and create as long as they deliver’ as if this was a new idea. He says he is fully committed to the NHS as a public service, but in a podcast at the end of 2023, Labour’s Plan for Power, he said he hopes to work with private sector companies on improving services and investing in new technology, and that entrepreneurs with great ideas to deliver better outcomes for patients and better value for money are ‘not going to struggle to get through the front door of the NHS’. There is nothing in Labour’s plans that is novel or which is going to stop the wrecking of the NHS.

Hannah Caller

FIGHT RACISM! FIGHT IMPERIALISM! 298 February/March 2024