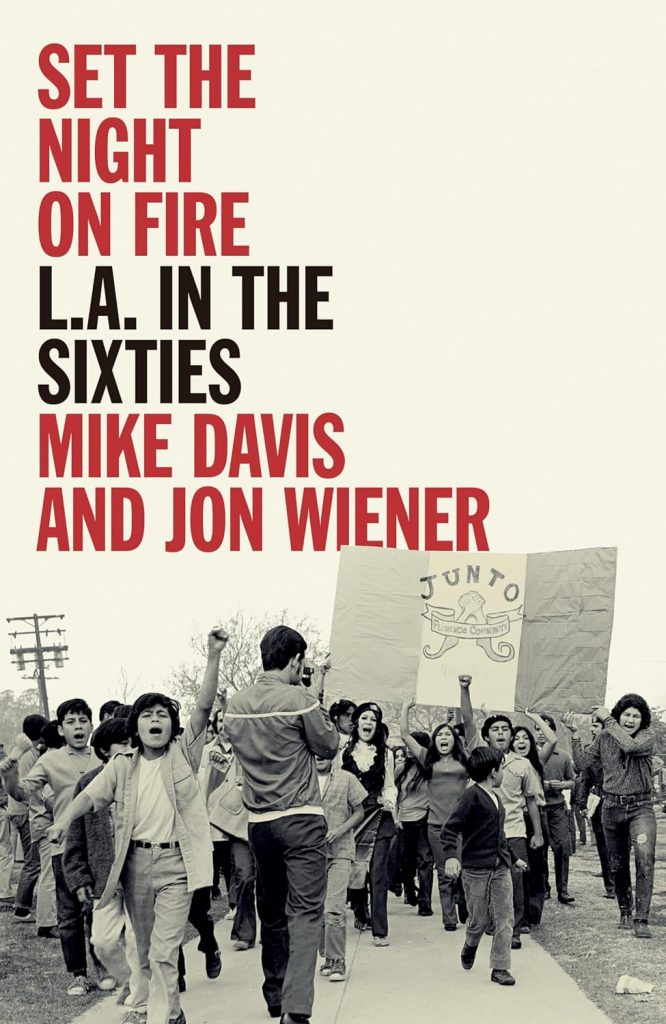

Set the Night on Fire: LA in the Sixties, Mike Davis and Jon Wiener, Verso Books 2020, £14.99 pbk

This book is a superb account of the racist realities of 1960s Los Angeles – and the struggle against them. For anyone who ever swallowed the claims of the powers-that-be in the coastal states to be fundamentally more enlightened than their contemporaries in the deep south, this book, which takes its title from the Doors’ 1967 hit single Light my fire, will be an eye-opener.

In the period covered by Davis and Wiener, LA was basically ruled by a toxic trio of vile racist bigots who would have been right at home in segregation-era Mississippi or Alabama: Mayor Sam Yorty, Police Chief William Parker, and last but not least, Cardinal James McIntyre, whom the authors refer to quite aptly as ‘consigliere to supreme Cold War cardinal [Francis] Spellman in New York’ before moving to LA (p114). (As anyone knows who has ever watched The Godfather or The Sopranos, ‘consigliere’ or adviser is one of the top posts in a Mafia family).

Housing in LA was a textbook case of informal apartheid overseen by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA): ‘Since the 1930s the FHA had underwritten exclusive practices and was continuing to subsidise mortgages in racially-restricted developments while allowing lenders to limit loans in minority areas’ (p13). This resulted in what Davis and Wiener call a ‘super-ghetto’: ‘75% of Los Angeles County’s black population [were] concentrated in the metropolitan core between Olympic Boulevard on the north and Artesia Boulevard on the south. Alameda Street, the old highway and railroad route to the harbour, was called the “cotton curtain” because blacks could not live or be seen at night in any of the dozen or so industrial suburbs to its east’ (p13).

All this was enforced by the state. At times we seem to be in apartheid South Africa. Davis and Wiener quote a former policeman Glenn Souza: ‘Black people could not venture north of Beverly or much west of LA area without a strongly documented purpose. In Hollywood Division, a negro was an automatic “shake”, or field interview, with the resultant warrant check or match-up to some vague crime report. A favoured location for these shakes was the call box at Outpost Canyon and Mulholland Drive. If there was absolutely no way to arrest the suspect, he was told to start walking’ (p46).

Decades of intolerable pressure created a highly combustible situation that finally exploded in the Watts uprising of August 1965. The black population of LA had had enough of police harassment. Feelings in the ghetto were well summarised by Martin Luther King Jr: ‘One young man said to me and Andy Young, Bayard Rustin and Bernard Lee, who were with me – “We won! We won!” I said “What do you mean, ‘we won’? Thirty-something people are dead [and] all but two are negroes. You’ve destroyed your own. What do you mean, we won?” And he said we made them pay attention to us’ (p225).

The state commissioned an inquiry. It was a total whitewash of the Yorty regime, not surprisingly as the inquiry was headed by ex-CIA director John McCone! Davis and Wiener quote the left-wing activist and co-founder of Mother Jones magazine Paul Jacobs: ‘In all of California…it would be hard to find a man less qualified by training and attitude to investigate a social phenomenon like the one that shook Los Angeles in August 1965’ (p229).

The period covered by Davis and Wiener coincides with the Vietnam War, and they make it clear that the burden of being used as cannon-fodder fell disproportionately on working-class, black and Latino communities whose members were unlikely to have connections to arrange deferments for them. Davis and Wiener estimate that of the 27 million Americans eligible for the draft only two million went to Vietnam and they were overwhelmingly from these communities (p331), which not surprisingly formed the backbone of the anti-war movement.

The Yorty regime formally ended in 1973 with his defeat by Tom Bradley in the mayoral election. Not surprisingly, this first election of a black mayor of LA did not bring great changes beyond having a few black faces in prominent posts. Nonetheless the struggles of black people in Los Angeles fed into deeper undercurrents of struggle, including the emergence of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. The Black Panther Party was founded just 100 miles away in Oakland, a year after the Watts Rebellion. It is clear that whatever the working class and oppressed nationalities achieve is the result of vast social struggles, as described by Davis and Wiener in detail to which this review could not even begin to do justice.

Mike Webber

FIGHT RACISM! FIGHT IMPERIALISM! 303 December 2024 /January 2025